A long time ago when Bob Newhart hosted Saturday Night Live, he did a bit during his opening monologue in which he spoofed early television travel documentaries. Newhart played the role of the narrator, describing his expedition into the wilds of Peru. He described his arrival at villages inhabited by Indigenous peoples who “were quite superstitious.” The arrival of Newhart’s party, the story went, coincided with a total solar eclipse. In response, “the natives began to beg us to please return the big red ball in the sky. Which we did of course. It just shows you there are lighter moments in even a trip as serious as ours.”

The entire premise of Newhart’s routine rested on the audience’s assumption that the Indigenous peoples were unsophisticated rubes, completely unable to understand celestial phenomena. Of course Indians would wonder what happened to the sun during an eclipse, because they could not possibly know any better.

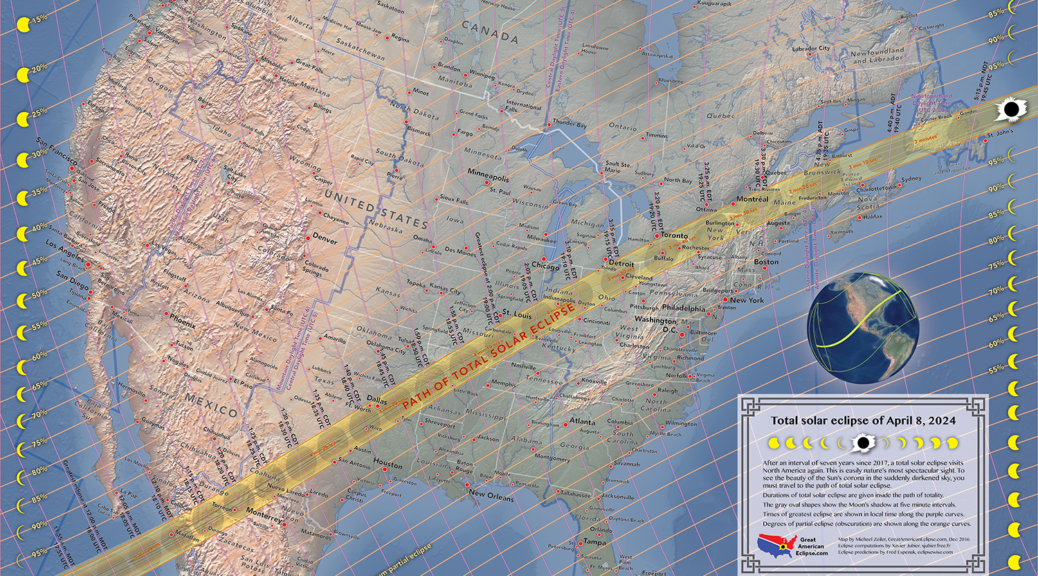

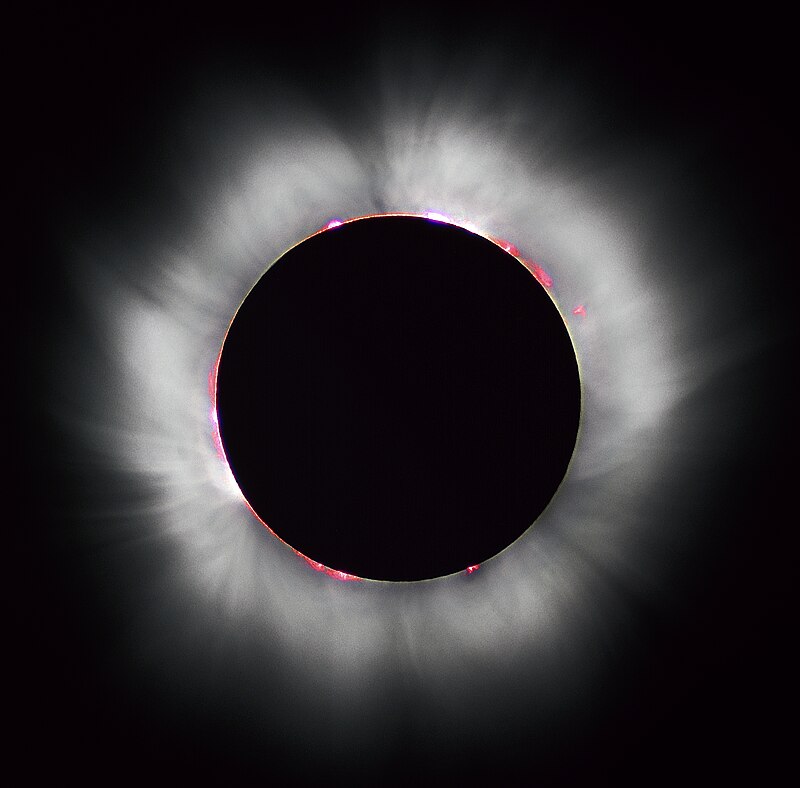

I have thought about this routine a lot, as the Great American Eclipse approaches in April of 2024. This total solar eclipse will be visible across much of upstate New York, and my college’s money makers are hoping to draw people to campus to witness the event. (Reminders of how cloudy, cold and wet Aprils in Upstate New York can be are completely unwelcome). Even some of our own promotional materials—shown to prospective students during an admitted students weekend–made reference to primitive peoples’ befuddlement at the appearance of eclipses. I wonder, however, if we are being too uncritical, and too dismissive of the sophistication of Indigenous peoples’ understandings of the stars, the skies, and all that they contain.

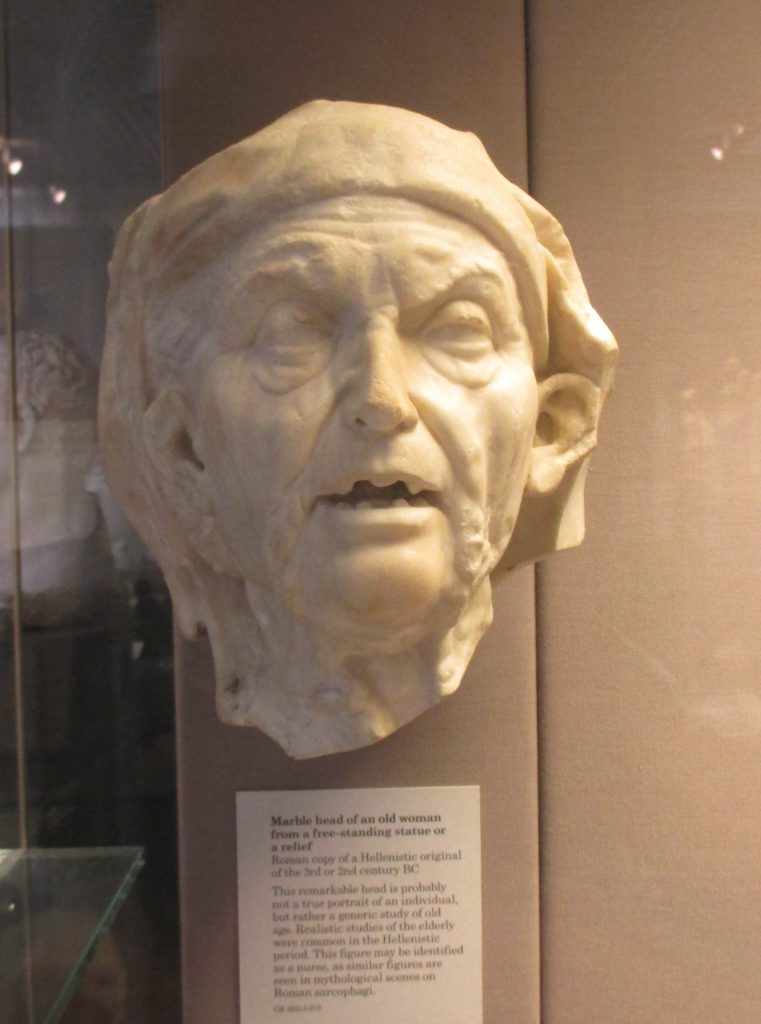

Herodotus, the ancient Greek historian, said once that a solar eclipse stopped the war between the Lydians and the Medes. The warring parties saw the eclipse as a sign they should make peace. In the Bible, darkness at noon figures prominently in the Passion Narratives, a portent of doom if we look to the Old Testament Book of Amos which, for instance, the Gospels copied in the telling of the Crucifixion. The death of the English king Henry 1 in 1133 shortly after an eclipse may have helped spread the superstition that eclipses could be bad news. In Plains Indian Winter Counts, Indigenous historians recorded comets and eclipses. They were events worthy of note.

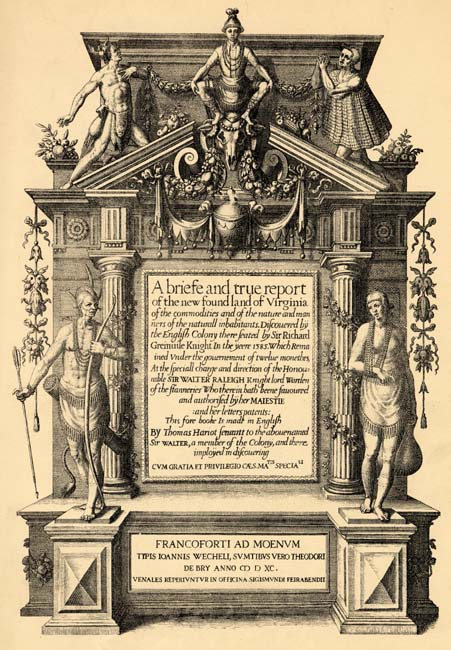

So, two stories. In his account of the year he spent at the first Roanoke Colony from 1585 until 1586, Thomas Harriot described the coastal Algonquians’ reaction to the English newcomers. They could not tell whether the English were “gods or men,” Harriot said. The Carolina Algonquians felt this way because of the inexplicable disease that seemed to accompany the English, the “invisible bullets” that the English were somehow able to fire with lethal accuracy at those who offended

them. The technology the English carried with them, items that seemed “so strange to them, and so far exceeded their capacities to comprehend the reason and means how they should be made and done, that they thought they were rather the works of gods than of men, or at the leastwise they had been given and taught us of the gods. Which made many of them to have such opinion of us, as that if they knew not the truth of god and religion already, it was rather to be had from us, whom God so specially loved than from a people that were so simple, as they found themselves to be in comparison of us” further encouraged this feeling. Finally the English arrival closely followed some significant astronomical events: a comet, for instance, and an “Eclipse of the Sun which we saw the same year before in our voyage thitherward, which to them appeared very terrible.”

That was what Thomas Harriot heard in the 1580s. So let’s jump ahead to 1925, for an event that the Brooklyn Citizen said took place on the Onondaga Nation in central New York. The Onondagas were gathered in the Nation’s Longhouse that January to commemorate their mid-winter rites. And then:

Interrupted in the midst of their annual ten-day penitential and atonement sacrifice by the eclipse of the sun, Indians at the Onondaga Reservation were crazed by fear. Darkness descended on the Indians as they were gathered in the famous old Longhouse to offer up the sacrifice of the White Dog to tehir God in atonement. As the light turned blue and then purple, they rushed from the buildings and led by an old chief, began firing at the eclipse. As the last shot rang out, the moon passed from the sun and the purple light began to fade. In a few moments it was normal again, and the Indians returned to the Longhouse, confident they had driven away the evil spirit.”

Think about these two stories. Think about how the authors know what they know. Think about which of them ring true to you. If I were to ask you to identify the story you thought most likely to be untrue, which would you choose? One, or the other, or both?

I suspect you might choose the second one. But I am skeptical about the first one as well. Harriot did not see the Indians’ reaction to the comet or the eclipse. The idea that Indigenous peoples were easily befuddled by astronomical phenomena is not entirely convincing to me. If we assume that freaking out at the sight of an eclipse is a sign of savagery, and a sign of possessing a lack of sophistication, and possessing a great deal of stupidity, it is not surprising perhaps that some writers might use an eclipse as another racist trope describing Indigenous backwardness. The sun disappeared, and the Indians wondered if it would ever come back!

But isn’t there another possibility? Isn’t it possible that Indians observed eclipses, saw the sun disappear, and then return, and then understood that eclipses were not all that big a deal. If I am right about this, it is entirely possible that Indians did not freak out at all at the sight of an eclipse. They might have said, “Huh, that’s weird,” and went about their day.

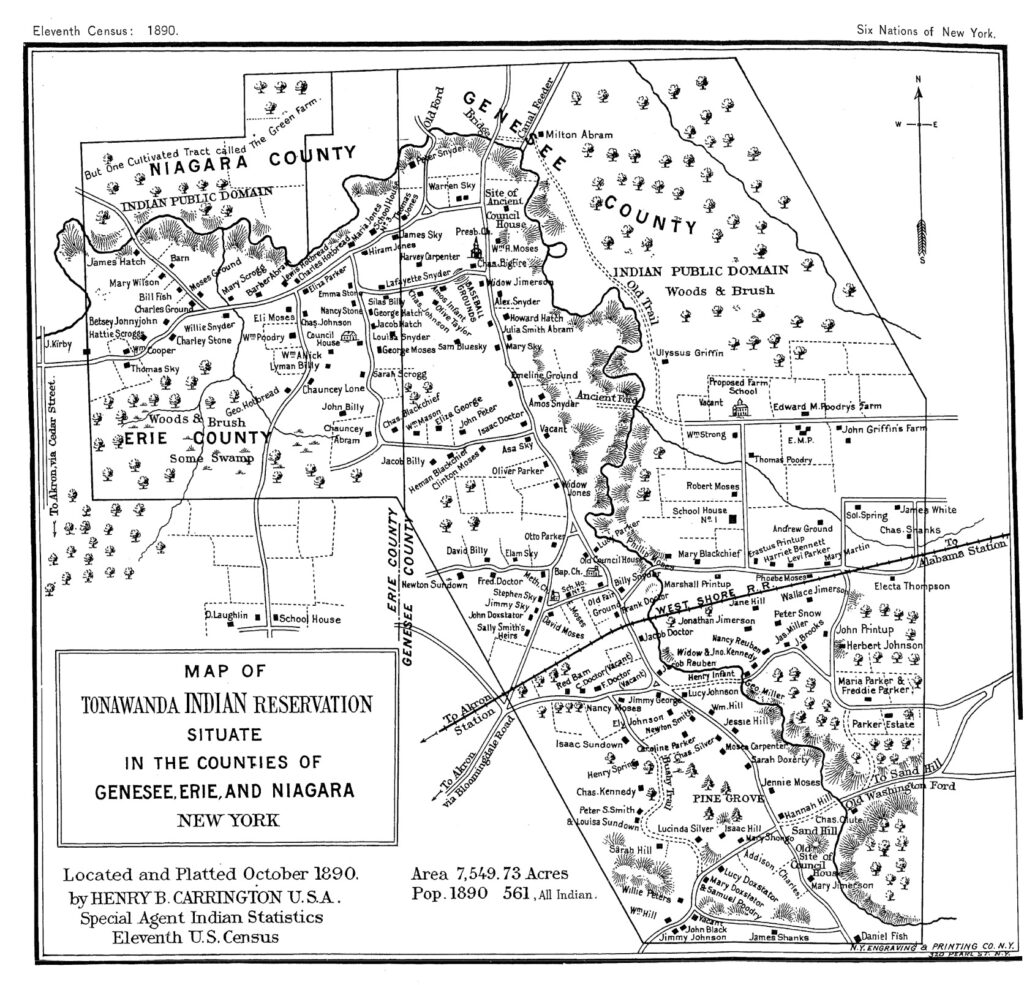

Don’t underestimate Indigenous peoples. Do not underestimate people who, as the anthropologist Lynn Ceci asserted long ago, knew to time the planting of their corn by the appearance or disappearance of the Pleiades. Indigenous peoples watched the sky closely. The evidence that this is true is so abundant. There is, as well, abundant evidence showing the sophistication of Indigenous observations of the cosmos. The astronomer Anna Sofaer called buildings at Chaco Canyon in the American Southwest “cosmological expression through architecture.” Some Indigenous peoples could predict astronomical events with great  precision. So come to Geneseo. With 165 sunny days per year, there is slightly less than a 50% chance that you will be able to see the eclipse clearly, but what the hell. You could go to Dallas and be almost assured of a sunny day, but we don’t judge. I do ask, however, that you not perpetuate unproven stereotypes about eclipses, and that you not diminish the wisdom of the peoples whose lands you will be visiting the moment you arrive.

precision. So come to Geneseo. With 165 sunny days per year, there is slightly less than a 50% chance that you will be able to see the eclipse clearly, but what the hell. You could go to Dallas and be almost assured of a sunny day, but we don’t judge. I do ask, however, that you not perpetuate unproven stereotypes about eclipses, and that you not diminish the wisdom of the peoples whose lands you will be visiting the moment you arrive.