The Federal Constitution of 1787 clarified and significantly strengthened the powers of the national government to conduct and oversee Indian affairs, at least on paper. That little debate or discussion of Indian policy took place at the Philadelphia Convention in 1787 suggests that the vast majority of the delegates believed that the administration of Indian affairs and the conduct of Indian policy should be placed firmly and unambiguously in the hands of the new national government. Certainly to James Madison one of the most pressing inadequacies of the Articles of Confederation had been the de facto weakness of the national government in the realm of Indian affairs. Madison had been disturbed by the conduct of the state of New York in its dealings with the Six Nations, but thought that “whatever may be the true boundary between the authority of Congs and that of N.Y., or however indiscreet the latter may have been . . . temperance on the part of the former will be the wisest policy.” He feared the consequences of a clash with defiant state authorities. During the Philadelphia Convention, Madison pointed out that “in certain cases the authy. of the Confederacy was disregarded, as in violations not only of the Treaty of Peace [with Great Britain], but of Treaties with France & Holland, which were complained of to Congs. In other cases,” he continued, “the Fedl. Authy. was violated by Treaties and wars with Indians as by [Georgia].” He listed the behavior of the states in the realm of Indian affairs as one of the principal “vices of the political system of the United States” under the Articles of Confederation.

President George Washington and his Secretary of War Henry Knox, who together designed and implemented the Indian policy of the new nation, believed that they must preserve order along the new nation’s frontiers. Post-Revolutionary claims that the Indian allies of Great Britain had been conquered during the war went unheeded by powerful Indian confederacies in the North, the Northwest, and the South. Washington and Knox recognized that the pretense of conquest, coupled with the government’s inability to control its land hungry settlers, could only involve the young republic in a continuous cycle of expensive warfare, something that the new nation simply could not afford. The United States under its first president embarked on a policy consistent in its approach with the earlier goals of the British empire, and consistent with the desires of many men who oversaw Indian policy during the Confederation years. This was a policy directed, in the words of historian Francis Paul Prucha, toward the “conciliation of the Indians by negotiation, a show of liberality, express guarantees of protection from encroachment beyond certain set boundaries, and a fostered and developed trade.” To implement such a policy, more was needed than the guarantees contained in Indian treaties. Something had to be done to restrain frontier whites and the governments of the several states. Hence the Indian and Trade and Intercourse Acts.

Indeed, Washington wrote to his Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton, expressing his firm belief that peace with Indians was impossible “while land-jobbing and the disorderly conduct of our borderers is suffered with impunity, and whilst the States individually are omitting no occasion to interfere in matters which belong to the general Government.” Referring specifically to New York, the President continued that “the interferences of the States, and the speculations of individuals, will be the bane of all our public measures.” Hamilton agreed entirely with the President, lamenting that “our system is such as still to leave the public peace of the Union at the mercy of each State government.” There can be no doubt that Congress enacted the Trade and Intercourse Acts to defend Indians from violent and corrupt frontier settlers and the aggressive actions of the several states.

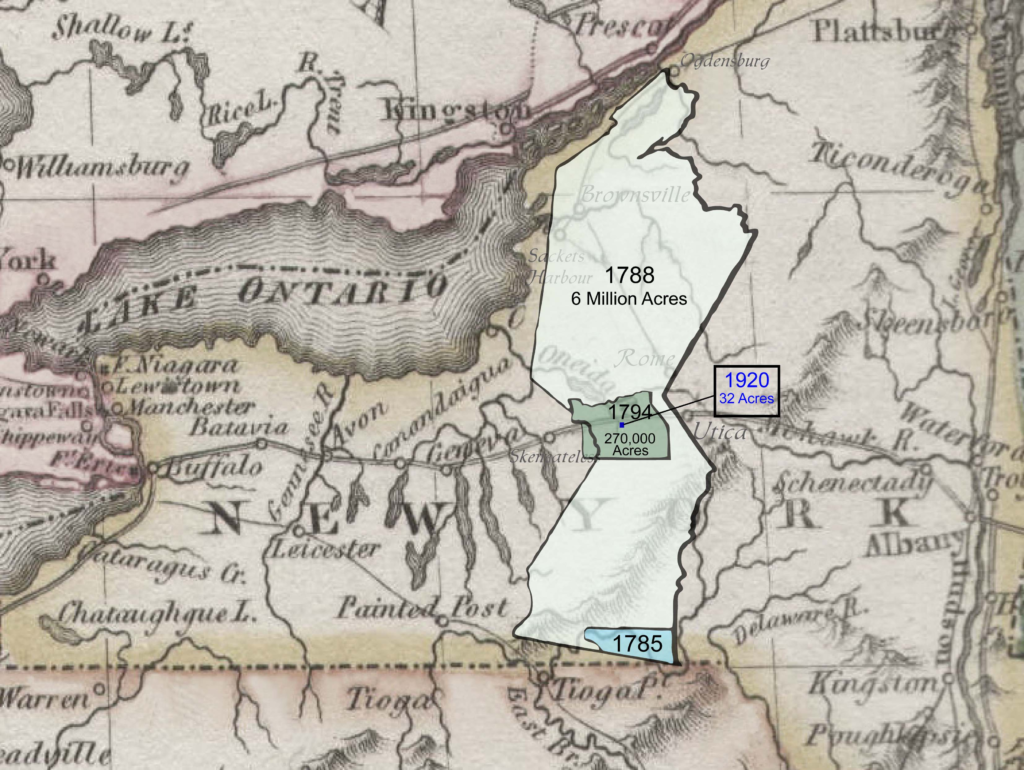

Considerable disaffection remained among the Six Nations after the Revolution. The Senecas, the westernmost and most populous member of the Confederacy, felt particularly aggrieved by the terms of the punitive 1784 Fort Stanwix Treaty. The United States had demanded that they surrender their claims to lands in the west. Others of the Six Nations expressed to President Washington anger regarding the state cessions of the Confederation era. Little could be done about those treaties, the President believed, because “these evils arose before the present Government of the United States was established, when the separate States, and individuals under their authority, undertook to treat with the Indian tribes respecting the sale of their lands.”

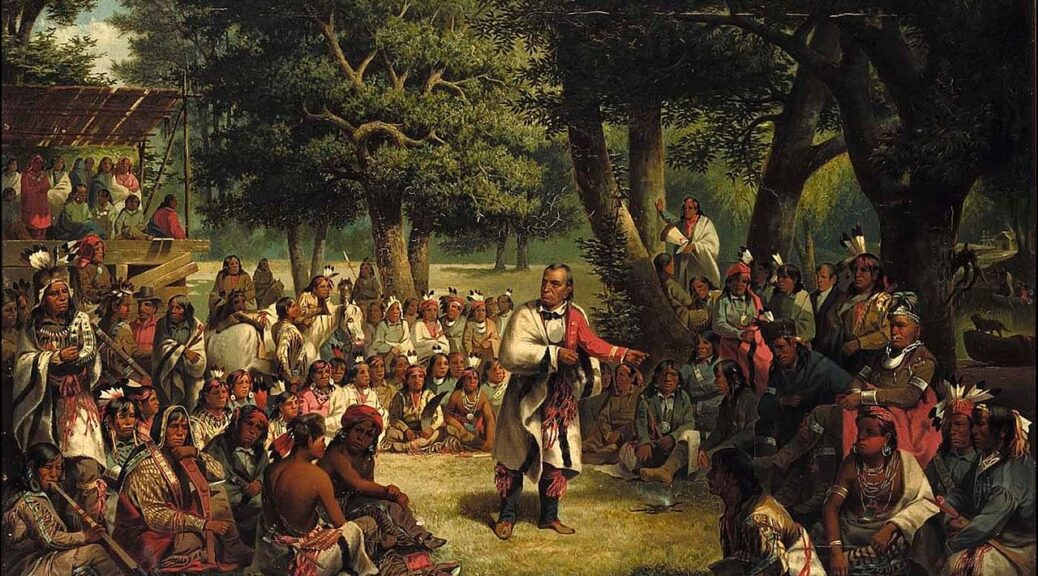

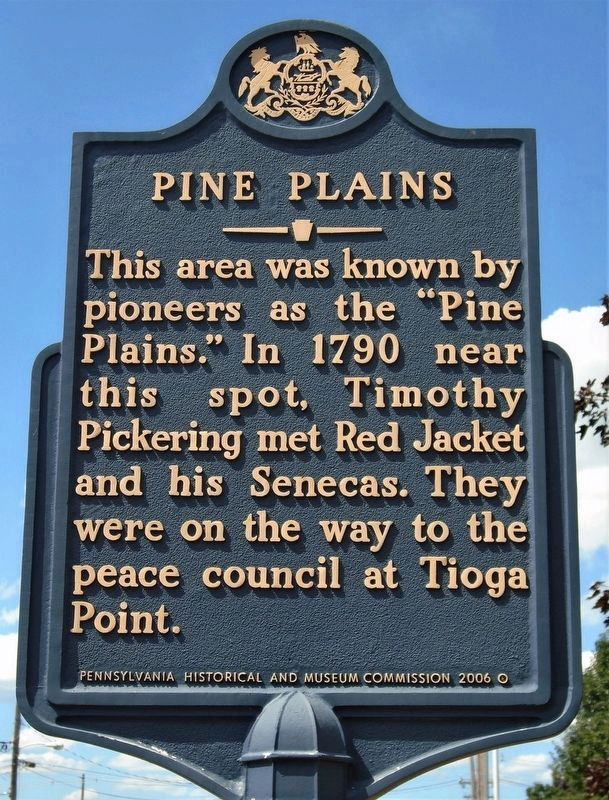

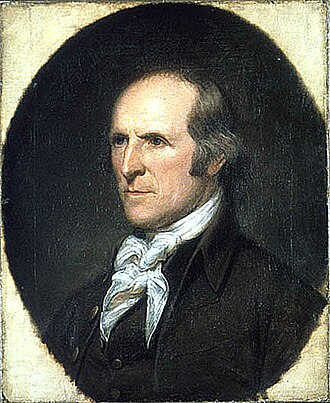

And land, of course, lay at the heart of the nation’s conflicts with Indians. Armed with the new United States Constitution, the Trade and Intercourse Acts, and worried about the prospect of Iroquois warriors supplied by the British joining the powerful Ohio River confederacies, the President was determined now to set things right. The attention of the United States focused most heavily on the western tribes in the Ohio Country, who had badly defeated American forces on a number of occasions. The Six Nations, however, were not ignored. United States officials first met with the Senecas at Tioga Point in 1790. Timothy

Pickering, who had been appointed by the President to meet with the Six Nations, was not entirely prepared to meet with as many Indians as arrived at the council, but he learned quickly what was expected of him. He followed Washington’s instructions and informed the gathered Indians “that all business between them and any part of the United States is hereafter to be transacted by the general government.” Shortly thereafter, the President met at Philadelphia with Cornplanter, the great accommodationist Seneca leader, and informed him that “the General Government only, has the power to treat with the Indian nations, and any treaty formed, and held, without its authority will not be binding.”

In 1791 Pickering again met with the Iroquois, this time at Newtown. Pickering once again tried to conciliate the Six Nations, and he discouraged them from joining the powerful Ohio Valley communities who recently had done so much damage to the American armies sent to subdue them. If Pickering overstepped his bounds in approving two leases of Iroquois lands to non-Indian members of the tribe, nobody seemed that concerned about the affair. Certainly, in 1794, Washington felt comfortable reappointing Pickering to meet with the Six Nations at Canandaigua.

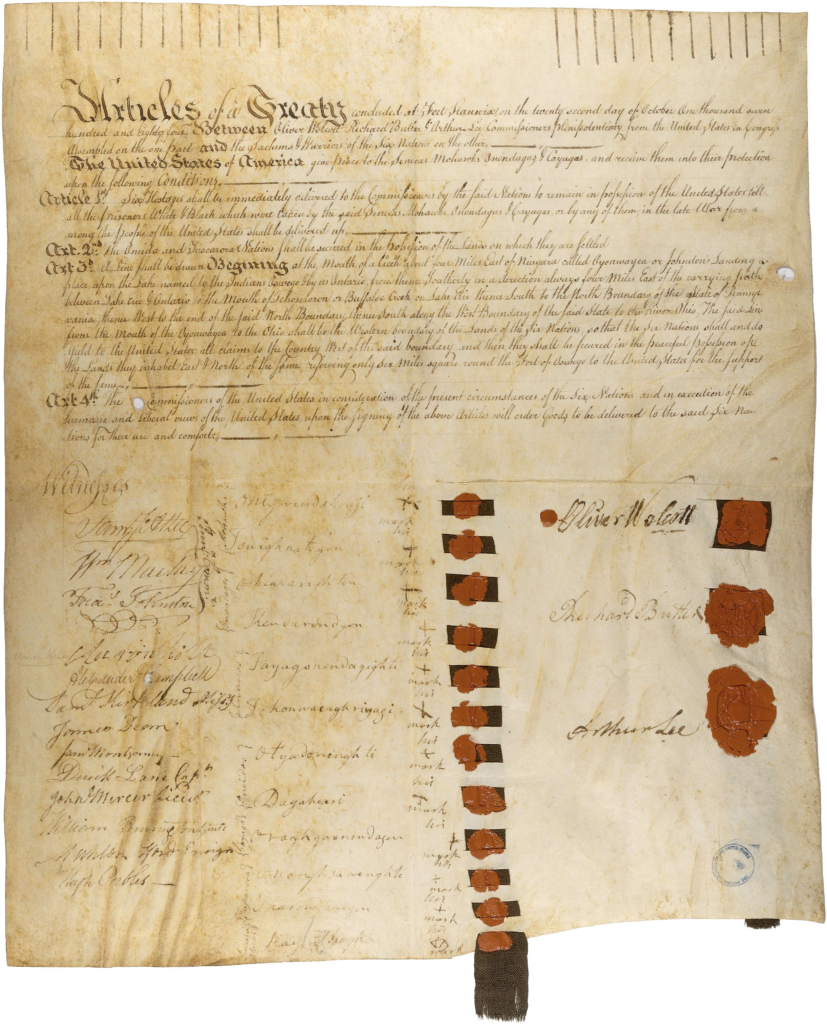

When Pickering gathered with the Six Nations at Canandaigua in the autumn of 1794, he hoped to resolve the long-standing difficulties with the Senecas. Seneca land, anthropologists Jack Campisi and William Starna point out, “was the central issue and Seneca neutrality the crucial concern. The participation of the other tribes was more ceremonial and clearly incidental to the treaty’s primary purpose.”

Still, the Oneidas attended the Council at Canandaigua and they raised concerns that Article II of the finished treaty ultimately addressed. Indeed, the Oneidas arrived early at Canandaigua, giving Pickering an opportunity to meet with them before the formal commencement of the treaty. They told Pickering that they felt troubled. “Our minds,” Captain John told Pickering, “are divided on account of our lands.” These difficulties could not be blamed upon the Oneidas. “’Tis you, Brothers of a white skin,” Captain John said,

who cause our uneasiness. You keep coming to our seats, one after another. You advise us to sell our lands. You way it will be to our advantage.

Pickering responded to the Oneidas’ speeches on the 13th of October. He told the Oneidas that they should, in effect, become civilized by learning to work the land like white men. They should as well learn to read and write, for it would then be less likely that “bad whites” could dispossess them through agreements the Indians did not understand. Pickering did more than lecture the Oneidas on their shortcomings, however. He was sympathetic to their plight. He reminded them that they did not need to part with their lands. He reminded them of a law of the United States intended to guard

the Indians from the impositions of White People. The most important article of this law respects your lands. This article declares that no sale of Indian land should be valid, unless made at a public treaty held under the authority of the United States.

In Article II of the completed Canandaigua Treaty, the United States acknowledged “the lands reserved to the Oneida, Onondaga, and Cayuga Nations, in their respective treaties with the state of New York, and called their reservations, to be their property.” The United States, moreover, would never claim these lands and “the said reservations shall remain theirs, until they choose to sell the same to the people of the United States, who have the right to purchase.”

Much of this should sound familiar to you. We have discussed some of this in the earlier posts in this series. But it is important to note that New York officials did not believe that the Trade and Intercourse Acts bound them, and they continued to take any opportunity to acquire Iroquois land that presented itself. In 1793, the state had acquired land from the Onondagas in a duplicitous treaty. The state of New York had been trying to obtain the Oneidas’ lands as well. In January of 1793 a small number of Oneidas petitioned the New York State Assembly. They did not have enough land to live upon by hunting, they said, and they hoped that the state would permit “that we might lease it out to your people, and receive the proceeds to ourselves.” They had no interest in selling their lands, and wished the state to appoint “some good men as agents to assist us in leasing our land.” Landlordism would allow the Oneidas a revenue now that hunting had failed them.

The state appointed commissioners, but they came to purchase the Oneidas’ lands, not to arrange a lease. When commissioners John Cantine and Simeon DeWitt met with the Oneidas, they immediately sensed that large numbers of Oneidas were opposed to any grant to the state of New York. The Commissioners moved quickly, recognizing “that the only prospect of success in our mission would depend on the agency of persons who had influence with them.” They hired James Dean and Samuel Kirkland to serve as interpreters, “whose connection and acquaintance with the Indians are well known, and whose fidelity in cooperating with us left no doubt that everything that could consistently be done was done to obtain the Object of the State.” What those objects were, and what the state commissioners told the Oneidas, were two different things. The state needed the lands of the Cayugas, Onondagas, and Oneidas if it were to develop the state’s frontiers. In return for acquisition of these lands, the state said it would pay to the Oneidas an annual rent for their lands.

The Oneidas’ response must have disappointed the state commissioners. The community was divided. Jacob Reed told Cantine and DeWitt that the petition was a mistake, the result of a misunderstanding between them and their federal superintendent Israel Chapin. The Onondagas and Cayugas had asked Chapin to petition the state legislature “for the privilege of leasing their lands, as their hunting failed and had become insufficient for their support.” Chapin, apparently, had assumed that the same would be advantageous for the Oneidas and, Reed said, Chapin “made the same request in their behalf.” Whether or not Reed had his facts straight, none of the Oneidas seemed to want to enter into a relationship on the terms the state commissioners offered. Reed apologized to the commissioners for troubling them and said “we were misled in our Petitions and we therefore sink it in the Earth and thus annihilate.” Captain Peter, another Oneida sachem, and Good Peter’s son, pointed out that the state had said that it would not ask the Oneidas for land again “for hundreds of Years.” Slyly, he suggested that “perhaps we have misapprehended your meaning—perhaps instead of years you Meant nights.” The Oneidas, Captain Peter continued,

do not chuse to dispose of any more of our lands. It is common for brothers not to agree when they are about making bargains. We cannot think now of selling any more lands we therefore hope that you will not press us to it.

Cantine and DeWitt appear to have been deeply frustrated. They continued their appeals, but the Commissioners’ arguments did not sway the Oneidas. As Jacob Read told them,

Brothers–You know it is a common case that people undertake business and do not succeed in it–that often bargains are almost completed and then dropt–Let this be the case now since we cannot agree to part with our lands[,] let us part in peace–We wish you to possess your minds in peace–We informed you yesterday what our determination was and we intend to abide by the same–We think our reservation already small enough; we wish not to contract it any more.

Of course the New Yorkers did not possess their minds in peace, and the state’s commissioners continued to try to obtain Iroquois lands. Timothy Pickering had appointed Israel Chapin, Jr., to succeed his recently deceased father as agent to the Six Nations in the spring of 1795. Because, Pickering believed, the Canandaigua treaty had secured peace with the Six Nations, he instructed the younger Chapin that

your principal concern will be, to prevent the tribes under your superintendence, from injury and imposition, which too many of our own people are disposed to practice upon them; diligently to employ all means under your direction, to promote their comfort and improvement, and to apply the public money and goods placed in your hands with inviolable integrity and prudent economy.

Chapin was happy to have the job and told Pickering that “it will ever be my ambition to support and maintain that mutual friendship and intercourse which has so happily existed between the Six Nations and the people living on this frontier.” Still, Chapin pointed out that it was going to be a tough assignment. Canandaigua was far from Oneida, making “it difficult for the Superintendent to pay so strict attention to them as would be necessary.” He suggested that Pickering appoint an additional agent.

Chapin appears at least to have tried to do his job, though it also appears that he was in well over his head, and not a competent representative of the government of the United States. He learned that the state intended to hold treaties with the Cayugas and Onondagas, and informed Pickering of this. The new secretary of War instructed his agent to halt the proceedings and he obtained from the Attorney-General of the United States, William Bradford, an opinion declaring that New York’s actions violated the Trade and Intercourse Acts. Bradford stated that the Indian Trade and Intercourse Act of 1793 was constitutional, and that New York could not purchase Indian lands “but by a treaty holden under the authority of the United States, and in the manner prescribed by Congress.” Pickering demanded that Chapin give “no countenance to this unlawful design . . . as it is repugnant to the law of the United States to regulate trade and Intercourse with the Indian tribes.”

Before Pickering’s letter and Bradford’s opinion could arrive at Canandaigua, Chapin departed to accompany the Onondagas and Cayugas to their meetings with the state commissioners, led now by Philip Schuyler. Chapin, in a letter written on the last day of July upon his return to Canandaigua, informed Pickering of what had happened. A young man alone against the state’s determined commissioners, Chapin “inquired of Genl. Schuyler how he construed the laws of Congress in regard to holding treaties with the Indian tribes?” Schuyler “made very little reply by saying it was very well where it would correspond with that of the individual states.” Chapin clearly did not know what to do. Had he then knowledge of the contents of Pickering’s letter and the attorney-general’s opinion, he wrote, “I could have managed the business more to your mind but as I had supposed the Government of the State of New York had applied to the General Government and had obtained sufficient power to call the Indians to the treaty.” Chapin had been confused. He pledged to Pickering to leave at once for Oneida to try to “engage the treaty will not take place then under the present commissioners.”

Pickering seems to have recognized that Chapin had little chance of succeeding against the force of a determined state. “Seeing that the Commissioners” of the state “were acting in defiance of the law of the United States,” he wrote back to Chapin, “it was certainly proper not to give them a countenance; and as the law declares such purchases of the Indians as those Commissioners were attempting to make invalid, it was also right to inform the Indians of the law and of the illegality of the purchase.” Go to Oneida, Pickering said, but “the negotiation is probably finished ere now.”

Philip Schuyler rejected the federal government’s interpretation of the Trade and Intercourse Acts, and proceeded with the treaty. He learned from Chapin that the United States viewed the state’s actions as illegal. In the end, he acquired for the state nearly 100,000 acres of the Oneida homeland.

There seems now little doubt that New York violated the Trade and Intercourse Act with the 1795 purchase of Oneida lands. It is important at this juncture to account for the failure of the United States to enforce its own laws in New York state. The first point that needs to be emphasized is that the new national government, despite the fears of the Antifederalists who dominated New York politics in 1787 and 1788, was indeed a tiny entity. The 1790s, to put it mildly, was no era of big government. The total number of non-uniformed employees of the national government in 1801, the first year for which we have good figures, was less than three thousand, and the vast majority of these worked in customs or other revenue related functions, or for the postal service. Only 214 federal employees resided in all of New York state, nearly all of them in the immediate vicinity of New York City, and almost all of them employed in customs.

Chapin was on his own. The Trade and Intercourse Acts, the laws Congress charged him with enforcing, were not strictly speaking “Indian laws.” Rather, they were directed towards curbing the long list of abuses Indians had historically suffered from their white neighbors. In enacting the Trade and Intercourse Acts, Congress assumed that white settlement would advance and Indians retreat, and its intent through the laws was to insure that the process, in Prucha’s words, “should be as free from disorder and injustice as possible.” Agents simply lacked the power to secure order on the frontier and compliance with federal law. It is, sadly, an old and blood-drenched story.

Indeed, the government of which Timothy Pickering was a part had learned that it ought not to announce loudly its weakness. Take, for instance, the case of the 1794 Whiskey Rebellion, an event which has nothing to do with Indian affairs but is immensely revealing nonetheless about the weakness of the national government. The residents of four counties in western Pennsylvania had grown increasingly disaffected with a federal excise tax on whiskey enacted by Congress in 1791, part of Alexander Hamilton’s “Financial Program.” They resisted paying the tax and, on the 7th of August, 1794, President Washington decided to call out the militia in order to enforce the laws of the United States. By the time the troops finally arrived in the vicinity of Pittsburgh in October, all signs of rebellion had disappeared.The rebels may have melted away, but still the government could not successfully collect the tax. The Whiskey Rebellion, in this sense, simultaneously strengthened the Democratic Republican opponents of the administration who feared a powerful centralized government and demonstrated that the new national government was, in the end, a paper tiger. The stakes would be considerably higher were the federal government to be faced down by a defiant state.

The federal complaints against New York’s behavior in 1795 may, however, have impacted the state’s subsequent behavior. The Federalist John Jay succeeded George Clinton as state governor in the midst of the 1795 crisis. Jay, along with Madison and Hamilton, had been one part of “Publius,” the group who wrote The Federalist; Jay served as well as the first Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court. Presumably, he knew something of the Constitution. When Pickering informed the new governor that the state’s treaties with the Oneidas were illegal, Jay did nothing. The negotiations, he said, had been authorized and had commenced prior to his assuming office. But a short time later, when a group of Mohawks from St. Regis approached the new governor about their lands in the northern part of the state, Jay wrote to Pickering “to request the President of the United States to appoint one or more Commissioners to hold a Treaty with these Indians . . . to the end that the negotiation of this State with them relative to the Justice and extinguishment of their Claim or Claims may be conducted and concluded conformably to the act of Congress of 1 March 1793.” The new governor of New York clearly recognized the requirements of federal law, and specifically referred to the 1793 Trade and Intercourse Act.

Early in 1798, a group of Oneidas approached Governor Jay, seeking to sell to the state a portion of their lands. Jay appointed state commissioners to negotiate a preliminary agreement with the Oneidas. That effected, he told his visitors that he would “immediately apply to the President to have a treaty held, under the authority of the United States, for the purpose of perfecting and effecting the business.” President John Adams complied with Jay’s request, naming Joseph Hopkinson of Pennsylvania to serve as federal commissioner. The treaty was formally negotiated and approved on the first of June, Hopkinson wrote, in “the manner prescribed by the act of Congress, entitled ‘an Act to regulate the trade and intercourse with the Indian tribes.’”

When Governor Clinton replaced John Jay in 1799, he continued to follow the rules set by the federal government. In March of 1802, Henry Dearborn, Thomas Jefferson’s secretary of war, informed the President that Clinton had recently requested “that a commissioner, on the part of the United States, might be appointed to attend a treaty with the Oneida Indians, for the purchase of about ten thousand acres of land, which that nation is desirous of selling, and which has, heretofore, been leased out to white people.” Jefferson appointed John Tayler of New York to the post. Nine months later, the President laid before the Senate the Oneida treaty and along with a number of others, “all of them conducted under the superintendence of a commissioner on the part of the United States, who reports that they have been adjusted with the fair and free consent and understanding of the parties.” On New Year’s Eve, the Senate assented to the1802 accord, but President Jefferson never proclaimed the treaty, so its actual ratification remains in doubt.

The point of the foregoing discussion of the period following the ratification of the Federal Constitution is that New York, during this period, haltingly came to accept an oversight role for the United States government in land transactions with Indian tribes. The 1798 and 1802 agreements with the Oneidas, which in essence had been agreed upon in advance, the state acknowledged could not take effect until they had been approved by the United States Senate and the President. The United States government, though it possessed little effective coercive power to back up its decrees, did succeed over the course of the nation’s first fifteen years in persuading New York to follow federal law.

This compliance, however, proved short-lived, and after 1802 the state purchased Indian lands on its own without federal oversight. The National government did nothing to stop it from doing so, a phenomenon that requires some explanation. In March of 1805, state officials oversaw the negotiation of an “indenture” between the “Pagan” and “Christian” parties of Oneidas. The two parties agreed to divide their remaining lands into two parts, one controlled by each faction. As a result, state negotiators would begin to meet separately with “Christian” and “Pagan” Oneidas.

This “Christian Party” of Oneidas in March of 1807 negotiated a cession of two parcels of its land in return for a payment of an annuity based on the value of those lands. Two years later, in February of 1809, Governor George Clinton acquired from the Christian and Pagan parties additional cessions. The state acquired additional cessions in 1809 and 1810. Clinton’s successor, Governor Daniel D. Tompkins, acquired even more land from the Christian Party at a treaty held in February of 1811. The following July, “the Tribe or Nation of Indians called the Oneidas” ceded lands lying east and south of its reservation to the state. No commissioner or other representative of the national government oversaw these transactions, and none of the agreements received approval by the Senate of the United States or proclamation by the President.

The United States did maintain Indian agents in the state after 1802. Secretary of War Dearborn, in a proclamation issued on Valentine’s Day in 1803, informed Iroquois leaders that a federal agent and sub-agent “shall attend in your principal towns, a considerable part of each year, for the purpose of giving every aid in their power to such of you as shall discover a desire of making improvements in husbandry and manufactories, and to settle such disputes which may happen, that come within the limits of their power.” In Dearborn’s view, the agents would serve as missionaries in the name of civilization, trying to reclaim the Indians from their “savagery.” It is important to point out that Dearborn and his successors do not appear to have considered it the job of the agent to oversee land transactions; under the provisions of the Indian Trade and Intercourse Acts, that function would be handled by commissioners specially appointed for the purpose by the President at the request of the states. Dearborn did see the agents as playing a critical role in preserving peace on the frontier. “Brothers,” he told the chiefs,

As evil designing people often attempt to fill our ears with stories calculated to excite uneasiness in your minds, you are requested in the future not to fail giving information to the Agent and Sub Agent of any such attempt, without delay, as the most sure means of preserving the friendship which so happily exists at present between your Nations and your Father the President.

The next day, Dearborn commissioned Jasper Parrish as his “Sub-Agent of the United States to the Six Nations.” Stationed at Canandaigua, Parrish would work in conjunction with agent Callender Irvine, who served only from 1802 until 1804, and thereafter with agent Erastus Granger of Buffalo Creek. Dearborn ordered Parrish to “endeavor to obtain and confirm the good will and affections of the Indians, to introduce the arts of civilization, domestic manufactures, and agriculture.” He was to keep the Indians in his superintendence from drinking to excess, and report to the Secretary of War “every circumstance and event which may occur that is important to the government of the United States to be made acquainted with.” If Dearborn meant that land cessions be included within this list of circumstances, his agents failed him. Dearborn, in fact, complained in the summer of 1804 that he had not received regular quarterly reports from several agencies, among them Buffalo Creek. If the agents knew all that the state was up to with regards to the Oneidas, they do not appear to have communicated that information to the War Department on as regular a basis as Dearborn expected.

Chapin and Granger, indeed, did nothing to prevent the state of New York from purchasing Indian lands, a fact that has led the defendants’ experts to conclude that the United States approved of the state’s purchases. Yet there are a number of factors that can explain the inattention of the agents to the Oneidas.

First, the agents did not seem to see themselves as responsible for overseeing treaties and purchases of land from the Indians, nor would anything in their instructions, strictly construed, have naturally led them to that conclusion. Treaties, as we have seen in the case of the 1798 and 1802 Oneida treaties, generally had been overseen by commissioners specially appointed for that purpose by the President. Another problem stemmed from the declining importance of the Oneidas in considerations of frontier order. Federal officials involved in managing the frontier and preserving order had bigger problems to worry about. Parrish lived in Canandaigua, over one hundred miles from Oneida. Granger, at Buffalo, lived seventy miles farther still to the west. They focused their attention on the Senecas and those members of the Six Nations who had settled on the Seneca lands that remained after the 1797 Big Tree treaty.

Furthermore, Indian agency appears to have been part-time work for both Parrish and Granger. Like many early Americans, they were opportunistic, and they looked for chances to make money beyond their federal salaries. One way to do this was to work for the state of New York. As early as 1796, the state had hired Israel Chapin to deliver state payments to the Cayuga chief Fish Carrier. Chapin’s payment included the grant of a parcel of land one mile square. In 1804, the state forwarded to Parrish at Canandaigua “the annuities in specie due the Indians for the last two years, with directions to pay it over.” Parrish asked for Dearborn’s advice. Four years later, the two agents apparently saw in the payment of state annuities due to the Indians a healthy source of income. Granger told Governor Daniel D. Tompkins that he had learned “that the expense of transporting and paying over the annuities from the State of New York to the Oneida, Onondaga, and Cayuga Indians, has annually cost the state upward of five hundred dollars.” He and Parrish would do the job for $350. In their capacity as federal agents they already had to visit Albany and the different Indian tribes. These, Granger pointed out, “are reasons why we can do the business cheaper than any other person.” The United States government, if it was aware of the specifics, seems not to have objected to Parrish and Granger’s entrepreneurial spirit.

When the agents did return their attention to the duties of their agency, they found it an enormous job. Erastus Granger, for instance, wrote to Henry Dearborn in December of 1807, revealingly describing the difficulties he faced in protecting the Indians from their white New York neighbors. The Tuscarora chiefs, Granger reported,

Eventually Granger apprehended the culprits, and he believed that in this instance he had “broken up this gang of Villains.” Still, he told Dearborn that his efforts did not matter. The criminals, he believed, “will get clear on trial.”

made complaint to me that they had lost a number of Cattle, horses, and hogs, which they had reason to believe were stolen by the white people. At that time, I was about starting for the City of Washington, and knowing that their Cattle run in the woods, I concluded there was a possibility of their having strayed off–Accordingly I advertised them in different places. On my return to this place last spring, I learned tha tthe Cattle were not found, but more were not missing, & stronger proof of their having been stolen. I immediately undertook an investigation of the business, but before any discoveries were made sufficient to warrant a prosecution, four of the principal offenders made their escape to Canada.

One year later, in 1808, Granger elaborated for Dearborn on the problems he faced. The culprits had been caught, but none of them has been punished. The challenge, Granger said, was that “there exists in the minds of many white people a strong prejudice against Indians.” The New Yorkers, Granger said, “want to root them out of the Country, as they own the best of the land. Those people,” he continued, “are often on juries.” Exasperated, Granger believed that the desire of local whites for Indian land was too great to be controlled by two federal agents, and that the Six Nations would continue to suffer if they remained where they were. Granger called Dearborn’s attention to the Louisiana Purchase, that vast expanse of land west of the Mississippi River acquired by the United States from France five years before. If the United States, Granger suggested, “would dispose of a sufficient tract of land in that purchase to the Six Nations, so as to make it an object for them to remove, I think I could perswade them to go.”

Red Jacket, the great Seneca orator, saw the abuses his people suffered at the hands of white New Yorkers as a violation of the Treaty of Canandaigua. He complained to Dearborn’s successor, acting Secretary of War William Eustis, that

for three years past we have received injury from the white people. Our cattle and horses have been stolen and carried off; and although we have made complaint to your Agent yet we have not received any compensation for our losses.”

In Red Jacket’s view, the agents must restrain the citizens of New York from stealing Iroquois livestock, cutting Iroquois timber, and squatting on Iroquois lands. The agents, a frustrated Red Jacket said, “have told us they had not the means in their hands to make satisfaction. We want to know,” he insisted,

whether the fault is in them. if it is not, we wish you now to instruct them that whenever we make satisfactory proof of losses, sustained by the bad conduct of your people, they should immediately satisfy our minds, by a reasonable compensation, thereby forever maintaining that league and friendship so necessary to both nations.

Red Jacket’s critique of federal policy, along with Granger’s despondent admission that order would remain elusive as long as Indians remained in the vicinity of the state’s growing numbers of white settlers, reveals the dimensions of the problem that the United States faced in its desire for an orderly frontier.

Some began to consider seriously the possibility of “removing” the New York Indians to new homes in the west. Indeed, removal as a solution to the nation’s Indian “problem” had been discussed as early as 1803 by Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson acted on his ideas several years later in negotiations with the Cherokees. In 1813 his successor, James Madison, suggested to the Senecas that they abandon their remaining reservations and concentrate themselves at Allegheny.

Still, an important point must be made. Even where it discussed the possibility of removal, the national government believed that the process must follow the guidelines spelled out in the Indian Trade and Intercourse Acts. Shortly after the conclusion of the War of 1812, for instance, New York governor Daniel D. Tompkins wrote to President Madison suggesting to him the attractiveness of relocating the New York Indians to the far northwestern frontier. The acting secretary of war, Alexander Dallas, informed Tompkins that the President was interested. “I am instructed to inform you,” Dallas wrote, that President Madison desired greatly “to accommodate your wishes.” There were, however, “national views of the subject which must be combined with such a movement, on motives of state policy.” All land transactions with Indian tribes, Dallas concluded, are “delicate; and a removal of them from one region of the country to another, is critically so, as relates to the affect on the Indians themselves, and on the white neighbors to their new abode.” Any removal, in other words, must necessarily be overseen by the national government, since national interests were at stake. When William Crawford replaced Dallas a short time later he reiterated his predecessor’s message. Crawford believed, like Dallas, that settling a friendly tribe of “Civilized” Indians in the vicinity of the Western Great Lakes could do much to bring security to the region. Indeed,

the interest which the state of New York takes in this transaction, and the influence which the cession may have upon its happiness and prosperity, have induced the President to determine that a treaty shall be held, with a view to accomplish the wishes of your excellency, and to gratify the desires of the Indian tribes in question.”

Crawford undoubtedly believed that removal would benefit everyone, but he believed as well that it could occur only through a treaty called by the government of the United States.

By this point, Tompkins already had completed yet another state treaty with Christian Party Oneidas and, by the time Dallas’s letter arrived, he was well on his way to purchasing Grand Island and other islands in the Niagara River from the Senecas.

It is time to take stock, once again, and review what we have covered so far. First, the post-revolutionary interpretation the state advanced of its historic relations with the Six Nations was based on a misreading of the empire’s Indian policy, a program that sought always to centralize authority over the conduct of Indian affairs in the hands of the Crown or his chosen designates. Even during the era of the Articles of Confederation, the aggressiveness of Georgia, North Carolina, Franklin and New York in their relations with Indians within their claimed boundaries upset many members of Congress. The new constitution, written in 1787, ratified in 1788, and implemented in 1789, clarified the ambiguities of the Articles of Confederation and placed all power “to regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several states, and with the Indian tribes” in the new national government. The Indian Trade and Intercourse Acts effectively defined the federal role in Indian affairs under the constitution, and high government officials informed New York in the 1790s that its purchase of Indian lands violated federal law. Indeed, nothing any responsible United States official said in the 1790s should have led New York to the conclusion that it had the right to purchase Indian lands without the superintendence of the United States government. These federal warnings had an impact, however short-lived. Through 1802 the state conformed to the requirements of the Trade and Intercourse Acts.

Yet in the years after the War of 1812, federal oversight of Indian Affairs in New York was ineffective. The federal agents in the state, Erastus Granger and Jasper Parrish, were busy men, and the other work they did at times worked against federal interests. Granger, for instance, held multiple offices during his tenure at Buffalo and, quite accurately, can be viewed as much an employee of the state as an agent of the United States. Granger retired in 1818 and the Six Nations Agency was reduced to a “sub-agency” with Jasper Parrish remaining in charge. Parrish continued to handle the state’s Indian business, paying out state annuities in 1815 and 1816, for instance, to the Onondagas, the Cayugas, and to the “posterity of Fish Carrier.” New York State paid him $20 for his services. Later, state officials expected Parrish to guide a party of Onondagas to Albany to negotiate with the state for a sale of their lands. The point is that the defendants’ experts base their argument that the United States was complicit in Oneida dispossession in part on an assessment of the actions of two individuals (and only two) who spent perhaps as much of their time working for the state of New York as they did for the United States, and who did not feel it was their job to oversee matters relating to the transfer of Indian land.

In addition to the conflicts of interest that hampered their ability and, perhaps, limited their willingness to enforce the Trade and Intercourse Acts, was the continued difficulty of the agent and sub-agent’s assignment. Illness, at times, kept Granger from doing his job. The unwillingness of New Yorkers to listen to federal authority was a bigger problem. As early as 1805, Granger complained to Secretary of War Dearborn of white encroachments on the Cayuga Reservation. “The Indians,” he said, “complain and are uneasy.” “The settlers refuse to remove.” Furthermore, “two families of White People have lately gone and settled in the Oneida villages and set up taverns” despite the fact that a “great majority of the Nation are opposed to the measure.” Granger felt himself “at a loss how to proceed with those intruders.” He simply did not have the strength to force New Yorkers to obey the law.

The agents also had difficulty finding the supplies they needed, either in Albany or in western New York. In 1816 Granger reported to acting Secretary of War George Graham that the Indians were suffering greatly from a lack of provisions. He needed their annuity in cash immediately, for any shipment of goods and supplies would arrive too late to save the Indians. With the money, Granger hoped to purchase flour in Ontario and Cayuga counties. The money, he noted grimly, “I think will keep them alive.”

In addition to these difficulties, I would argue that the “United States” (assuming that we mean by this something more than its two isolated agents in western New York) knew little specifically about New York’s purchases of land from the Oneidas. In his annual “Statement” in 1816, Granger mentioned that the Oneida reservation was 180 miles from his place of residence at Buffalo. Notice, as well, when most of the Oneida transactions took place: early in March of 1807; in February of 1809; in March of 1810; in February of 1811; in March of 1815; and in March of 1817. Small delegations of Oneidas traveled from their reservation (180 miles to Granger’s east) to Albany (nearly 300 miles away) in the heart of New York’s winter, to negotiate with the state. Their instructions required that the federal agents travel to the different Indian reservations in the state, but only during “the warm season.” The Erie Canal was not completed until 1825, and prior to that travel would have been difficult even in good weather. There is no evidence that either Granger or Parrish attended the state treaties at Albany and, I would suggest, there is good reason to ask how long it took them to find out about these winter negotiations.

Even the information that the United States government officials eventually received about these transactions is not without its problems. For instance, in November 1818 a group of Oneidas petitioned President James Monroe, informing him that they had

sold to the State of New York a great proportion of their reservation, and being thereby constrained to live in the neighborhood of your white children, have imperceptibly acquired many of their manners and customs, arts and sciences, and having been taught by a pious and learned friend have acquired so much knowledge of the Christian religion as to have formed themselves into a congregation, and lately erected at their own expense a very expensive church.

The members of this “Second Christian Party”did inform the President that they had sold lands to the state of New York. The information came from neither Granger nor Parrish, and the most recent land transaction to which the Oneida petitioners could possibly have referred was the cession they negotiated at Albany in March of 1817. The United States, then, unquestionably learned by November of 1818 that the state at some point previously had purchased Oneida land. All the evidence suggests that it received this information nearly twenty months after the sale had occurred, and even then the information was imprecise about the nature of the transaction. Information arriving at the seat of the national government so late posed problems that could not easily be remedied.