I am wrapping up my thirtieth year in the classroom. Aware always that for every professor there are dozens of Ph.D recipients who would love to work in academia, but will never have the chance, I have worked hard to be the best teacher and scholar I can be. I am aware of the privileges I have enjoyed, and recognize the obligations that places upon me to do good work. Even with a heavy teaching load, large numbers of advisees, and spending my career at small colleges with few resources to support faculty research, I believe it is important to continually be productive and continually to grow and improve as a professor of history.

I began studying the history of Indigenous peoples as an undergraduate student at the California State University at Long Beach, to which I transferred after two years at a local junior college. I did not have the opportunity to work with members of Indigenous Nations until I began my academic teaching career at Montana State University-Billings, a small, open-admissions campus that was part of the larger Montana State University system. I taught survey courses in American history at MSU-B, the department’s required course in Historical Research Methods, and upper-division courses covering the Colonial, Revolutionary, and Early National Periods. I was an effective and popular teacher. I won the college’s Winston and Helen Cox Fellowship for the year 1996-1997, awarded annually to an outstanding junior faculty member, and one year later the Outstanding Faculty Award, presented by the Associated Students. But I most valued my work with the Crow and Northern Cheyenne students who attended MSU-B, from whom I learned much. Most of them were older students. They traveled a great distance, sometimes every day, to attend class. They struggled with the costs of college, and the burdens of caring for children and grandchildren while attending school. Almost none of them finished in four years. Some were perennial part-time students. Many of them took my course in Native American History, required for the Native American Studies major and minor, and they taught me a great deal about the power of working together.

For example, I began a research project on race relations between members of the Crow Nation and white residents in Hardin, Montana, a reservation border town in which half the population was Indigenous. A college provost demanded that faculty engage in what she called “applied research,” which seemed to mean “stuff that she felt mattered.” Early American history clearly was not on that list. So I began poking around. After Native American students at Hardin High School protested some callous treatment by non-Indian students, a white supremacist group distributed on doorsteps throughout Hardin a despicable racist pamphlet. I began to investigate the story. I could not accomplish as much as I wanted. As a single parent at that time, it was difficult to drive the 120-mile round-trip to Hardin and get much work done there, and I found it difficult to get anti-Crow white people to speak honestly and candidly about their town. But I did talk to sympathetic whites, and many Crow people, who described their lived experiences in Hardin, a town where residents remembered seeing “No Dogs or Indians” signs in downtown businesses. It was a searing experience. I never published on the topic, but the experience taught me at an early point in my career the obvious but often overlooked point that an important part of writing the history of a community involves forging relationships with members of that community. Collaboration, I learned, was integral to good community history. We can learn much from even those projects we do not finish.

Billings was a tough place to work as a professor while being a single parent. Resources were scarce, the pay was low, and the teaching load was seven courses a year. Most of us in the department worked summer jobs to help make ends meet. As much as I loved the students, I could not stay. I never completed the Hardin project because I left Billings in 1998 for a new position at the State University of New York, College at Geneseo. I had signed a contract with Cornell University Press to publish my first book, Dominion and Civility, and that provided an opportunity to make a move that was better for my family. Except for one year I spent at the University of Houston in 2009-2010, I have been at Geneseo ever since.

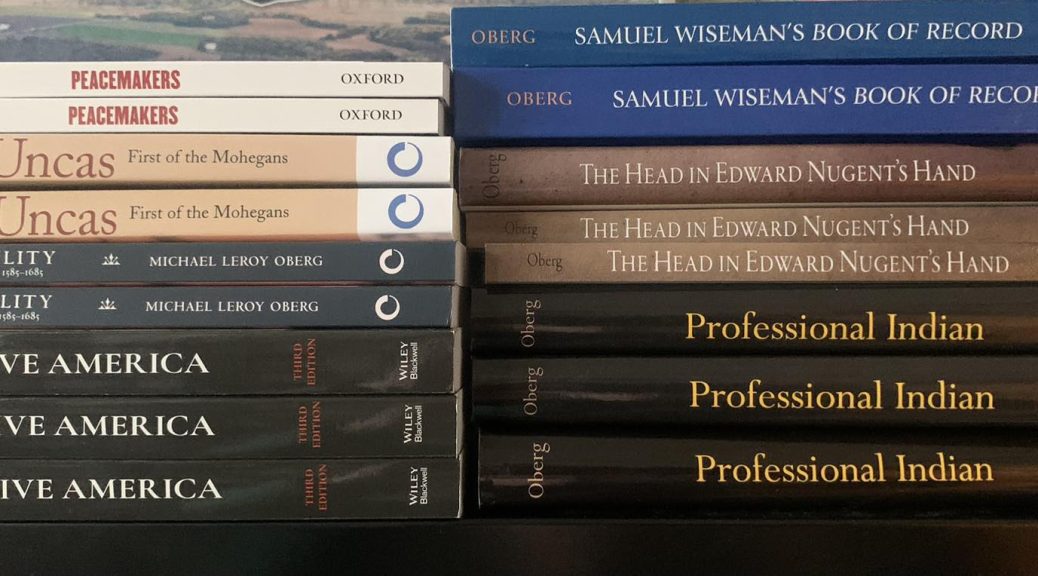

Geneseo, like Billings, is a small, underfunded, public college. Though Geneseo was a much more selective college at the time I arrived, my job was essentially what it had been in Billings: teach Colonial and Revolutionary US, Research Methods, and the college’s required course in the Humanities. I also developed and taught my Native American survey, a course on American Indian Law, and an upper-division course in Haudenosaunee history. At Geneseo, as in Billings, I succeeded in the classroom and as a scholar, winning the Chancellor’s Award for Excellence in Teaching in 2003, and the Chancellor’s Award for Excellence in Research and Creative Activities in 2013 (both the highest SUNY system-wide awards given in those areas). I was also named James and Julia Lockhart Professor from 2005 to 2008 and promoted to Distinguished Professor in 2015, the highest rank for any faculty member in the SUNY system. I published six books, including a textbook in Native American history now in its third edition, and developed the college’s minor in Native American Studies. At Geneseo, as in Billings, I greatly value the work I have done outside of the classroom with Indigenous peoples in New York State.

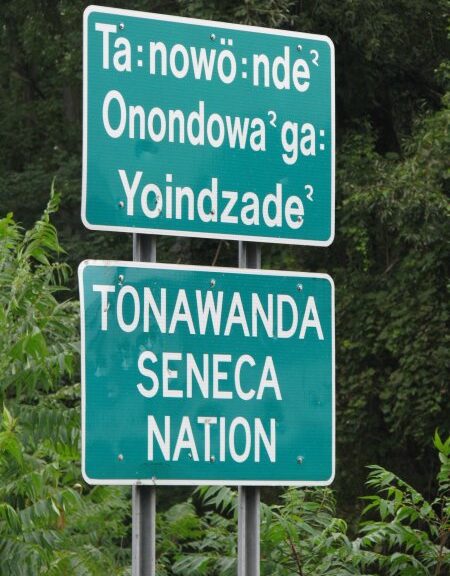

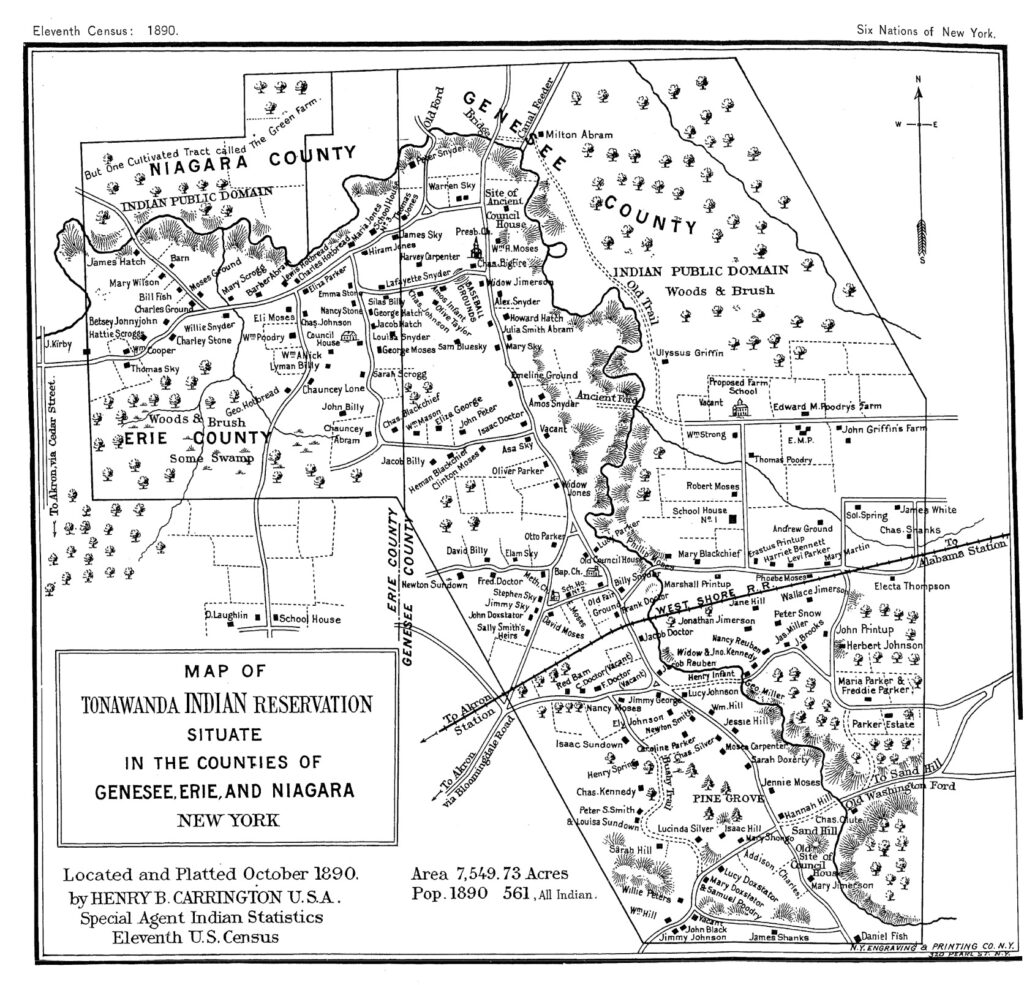

In Geneseo I was presented with opportunities that were not nearly as available in Montana. Shortly after my arrival in 1998, for example, I was invited by the Tonawanda Seneca Nation to provide research and expert witness testimony in their efforts to recover Grand Island, New York, purchased from them in 1815 by the state of New York in violation of the federal Indian Trade and Intercourse Act. It was the first of several Indigenous rights cases in which I was involved over the next two and a half decades. I was privileged to work with the Onondaga Nation, the Akwesasne Mohawks, and the Oneida Indian Nation, all on cases involving their efforts to recover lost lands. I have also worked on gaming and taxation issues involving Haudenosaunee nations in New York State. This work brought important benefits, and led to several of my book projects: Professional Indian: The American Odyssey of Eleazer Williams, and Peacemakers: The United States, the Six Nations of the Iroquois, and the Treaty of Canandaigua, 1794, both published in 2015.

Finally, collaborative work led to the book project I am hoping to finish very soon. In 2014 I began working with the Onondaga Nation on research related to cleaning up Onondaga Lake, once the most polluted body of water in North America. The Superfund law allows Indigenous nations to have a say in the cleanup process if they can demonstrate a cultural tie to the polluted site. My job was to demonstrate that connection. Over several years I completed a 700-page annotated bibliography, with links to copies of all the documents, illustrating this massive history. Working on the history of Onondaga Lake with the Nation led to work writing the history of the Onondaga Nation itself. It has been a massive project. It requires frequent trips to the reservation, 90 miles from my house. Nearly all the research is completed, and I am looking for time to finish the book, revise the manuscript, and work through the project with some of my collaborators at Onondaga Nation to produce a final draft. I have learned a great deal.

While work on the history of the Onondaga Nation takes up much of my time, since late 2018 I have served as the founding director of the Geneseo Center for Local and Municipal History. I am very proud of this work. New York, under law, requires every municipality, from the smallest crossroads to the largest city, to have an appointed historian. Many of these town and local historians are amateurs. They are elderly, and they may not have much or any training as a historian. But it seemed to me that partnering with them would benefit our students, help the historians, and increase the public’s awareness of their community’s history. As director, I have applied for five grants. Four of them have been funded fully:

* A small, $853 dollar grant that paid for our first organizing meeting.

* An $11,000 dollar grant from the Rochester Area Community Foundation to create an online Indigenous History of Livingston County in 2021 (Geneseo is the seat of county seat for Livingston County).

* A $176,000 grant from the National Endowment of the Humanities to fund the Center and to provide for 21 paid internships across New York State in September 2021.

* And a $453,000 grant from the Robert David Lion Gardiner Foundation to create the Gardiner Foundation Semiquincentennial Summer Fellowship Program. Because the Geneseo administration does not value this work, it will likely cease after this year. During its two years, I managed the program and placed fifty students from seven colleges in paid summer fellowships in local historians’ offices across New York State. I oversaw their work and help disseminate their efforts.

By the end of next year the Center will have placed 71 students from 7 colleges in high-paying fellowships across the width and breadth of New York State. Another fifty students, since early 2019, have completed independent studies on local history topics in their communities, and unpaid internships in their hometowns. Given that much of this work was done during the pandemic, I am very proud of what the Center has accomplished.

In the future, I intend for the Center to do more work to demonstrate that Native American history in New York is Local History. In collaboration with scholars at other universities, local historians, and representatives from Indigenous Nations, we have begun work on what we have dubbed “The 1779 Project” (The Van Schaick raid against the Onondagas and the Sullivan-Clinton expedition against the Senecas and Cayugas took place in 1779, a critical year for Indigenous New Yorkers during the American Revolution). We hope that by telling the stories of these American invasions of Iroquois land, we can complicate the history of the 250th Anniversary of American Independence, by placing Indigenous dispossession at the heart of New York State History in the same way that the “1619 Project” raised provocative questions about the important place of slavery in discussions of American liberty. The project, when we obtain funding, will include a book, curricula and lesson plans for New York teachers, a digital platform addressing the history of these expeditions and Indigenous dispossession in the state, and a series of book clubs and traveling lecturers giving talks about the Invasions of 1779. Our goal is to reach every school and every community in New York State by the time our work is completed.

I love undergraduate teaching. Apart from the four years I spent in grad school at Syracuse University, my entire career has been spent at undergraduate public colleges where teaching is job one. Despite the challenging times facing public higher education, when I meet my students, I remain optimistic about the future. But that is becoming more difficult than ever before.

Just this week I gave a talk sponsored by the Livingston County History Museum and the Association for the Preservation of Geneseo. I like the work both groups do, so I did not charge (I did accept an unexpected gift from both organizations.) My parsimonious college demanded that we pay $108 to have a representative from the A/V department open the cabinet that contained the microphone and the USB cord for connecting my laptop.

I know this is a small matter. I know that a hundred bucks and change is not a lot of money. But, as they say, it’s the principle. The point of all that I have written above is that I have worked very hard over the past thirty years. I have done some really good work. I know that I have taught many students, over many years, who will vouch for the work I have done. I understand all of this. But it saddens me that I have grown accustomed over the past few years at Geneseo under the college’s current leadership to going above and beyond in all my work and receive for it little recognition, no thanks, and continuous disrespect and humiliation shown by our callous leaders. What I cannot grow accustomed to is working hard and having to pay for the privilege. I would complain but I know by now that nobody in charge cares and that nothing will be done. I do not like whining, but I am thoroughly demoralized.

precision. So come to Geneseo. With

precision. So come to Geneseo. With