One of the most important events of the modern Indian rights movement began today at the small hamlet of Wounded Knee, on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. You should be teaching students in your American History class about Wounded Knee, not as an explosive event, but one with origins reaching back to the nineteenth century.

The occupation, indeed, had deep routes.

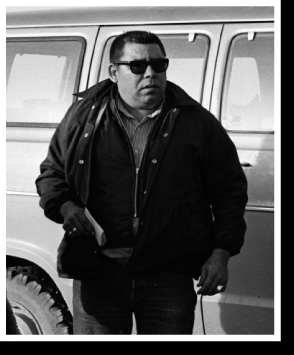

Several months after the occupation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 1972, the activism of the Nixon years reignited in South Dakota. In January of 1973, a white man killed a Sioux named Wesley Bad Heart Bull outside a bar in Custer County. Local authorities charged the attacker with manslaughter, nothing more, and AIM, the American Indian Movement, arrived to protest. Led by Dennis Banks, they asked the prosecutor to consider more serious charges. When he refused, a riot broke out. The protestors set the local Chamber of Commerce building on fire; local police and county sheriffs responded with tear gas and violence. Twenty‐two people were arrested, nineteen of them Indigenous peoples. In the aftermath of the Custer riot, elders at the Pine Ridge Reservation invited AIM to aid them in their struggles against tribal chairman Dick Wilson, the head of an Indian Reorganization Act government notorious for its corruption and strong‐arm tactics. THe New Deal era IRA led at times to tribal governments that did not fit with the traditional values of an Indigenous community, and that certainly was the case at Pine Ridge. Wilson maintained a personal police force, for example, the well‐armed GOON squad (Guardians of Ogalala Nation) to control and intimidate dissenters. He had defeated efforts by the Reservation’s residents to impeach him. His authority challenged, he called upon federal authorities for support: federal marshals with automatic weapons came to Pine Ridge, setting the stage for a showdown.

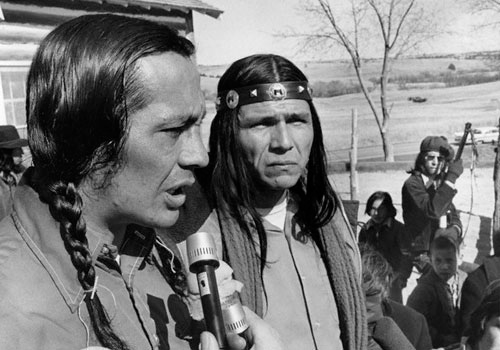

Led by Russell Means and Dennis Banks, AIM hoped to bring the attention of the world to the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. If they had little familiarity with tribal traditions—both had spent much of their lives in cities—they knew well how to draw the media and generate interest. On February 27, 1973, they and a group of their followers, perhaps 300 in all, occupied the small village of Wounded Knee, the site of the massacre of Sioux Ghost Dancers eighty‐three years before. Most of the occupiers came from the surrounding Lakota reservations, but they received support small numbers of Kiowas, Pueblos, Potawatomis, Senecas, and many others. Two Rappahannocks who had lived in New Jersey traveled west to join AIM at Wounded Knee. The occupiers had a handful of rifles; one of the occupiers had an AK‐47 with an empty banana clip. Some had served in Vietnam and felt keenly the injustice of the colonial system existing at Pine Ridge, where reservation residents had few rights and no redress. Desperate means called for desperate measures. Wilson’s GOONs and federal forces quickly surrounded the occupiers with an impressive array of the latest military technology: armored personnel carriers, high‐powered rifles, machine guns, grenade launchers, and armor. The federal authorities fired off more than 130,000 rounds of ammunition during the occupation. In cities like San Francisco and Washington, the Nixon Administration was willing to exercise restraint in its response to Native American protests. Federal authorities had avoided using a heavy hand during the occupation of Alcatraz and the Bureau of Indian Affairs headquarters in Washington, D.C. Not so on a remote reservation in South Dakota.

On March 11, the occupiers issued a statement declaring the independence of the Oglala Nation. “We are a sovereign nation by the treaty of 1868,” the occupiers said, and “we want to abolish the Tribal Government under the Indian Reorganization Act. Wounded Knee will be a corporate state under the Independent Oglala Nation.” They rejected the “reorganized” government of the Pine Ridge Reservation and objected to a corrupt government out of touch with tribal traditions and willing to harass and violently persecute its opponents. Means and Banks attracted a considerable amount of attention but they could not achieve their fundamental goals, for the federal government would not see to the removal of Wilson, or address the fundamental structural causes of so much misery on Indian reservations. The occupation of Wounded Knee lasted seventy‐one days. At its end, two of the occupiers had died, and one federal marshal received a wound that left him paralyzed. Given the number of rounds fired, that so few were killed and injured was something of a miracle.

The occupiers left Wounded Knee in May of 1973. According to Banks, “Wounded Knee was the greatest event in the history of Native America in the twentieth century. It was,” he continued, “our shining hour.” Leonard Crow Dog, the spiritual leader and another of the occupiers, agreed that “our seventy‐one-day stand was the greatest deed done by Native Americans.” Still, Crow Dog noted, “we never got our Black Hills back, the Treaty of Fort Laramie was not honored, nor did the government recognize us as an independent nation.” In the words of historian Paul Chaat Smith, “there was a clear‐eyed, if often unspoken, acknowledgment that frequently our elders are lost or drunk, our traditions nearly forgotten or confused, our community leaders co‐opted or narrow,” but “they knew only one thing for sure: business as usual was not working, their communities were in pain and crisis, and they had to do something.” AIM brought considerable attention to the problems Indigenous peoples faced. Thanks to the organization’s efforts, many American people became aware for the first time of their nation’s long history of injustices toward American Indians. These achievements were significant.

Still, federal authorities relentlessly harassed and prosecuted the leaders of AIM. After the occupation, Dick Wilson resumed his campaign of repression against what he viewed as outside agitators. This violence led to the killing of two FBI agents in June 1975. After some shady legal maneuvering, a federal court tried and convicted Leonard Peltier, an AIM member, despite significant doubts about his guilt and procedural irregularities at his trial. Peltier remains in prison today. Protests against Wilson’s regime did little to remove the fundamental problem: the United States, though willing to embrace self‐determination, and to consider piecemeal changes in its policies toward Indigenous peoples, never abandoned the notion that Indians remained wards of the nation. It is important to remember this. The federal government in the second half of the twentieth century favored self‐determination and, in specific cases, implemented programs and policies that addressed historic injustice and the poor conditions under which many Indigenous peoples lived. But it would only go so far. A tension existed, between self‐determination and wardship, between sovereignty and colonialism, that individual Indigenous peoples, tribal, local, state and federal governments, and the federal courts would wrestle with over the coming years. Indigenous peoples survived termination’s direct negation of their political rights, and gained more control over their lives, but the ambiguities created by the conflicting forces of sovereignty and colonialism remained.