One of my very good former students told me about “The Secret Path,” a multimedia project pro duced by Gord Downie, the lead singer of the Canadian rock band The Tragically Hip in the fall of 2016. An animated film, a musical album, a graphic novel, The Secret Path tells the story of Chanie Wenjack. Twelve years old when he fled from the Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School, Chanie wanted to return to his family at Ogoki Post, four hundred miles away. He did not know how long a journey he had, and he never made it home. He died from exposure, exhaustion, and hunger along the tracks that he thought would lead him to his family in October of 1966. Just a kid.

duced by Gord Downie, the lead singer of the Canadian rock band The Tragically Hip in the fall of 2016. An animated film, a musical album, a graphic novel, The Secret Path tells the story of Chanie Wenjack. Twelve years old when he fled from the Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School, Chanie wanted to return to his family at Ogoki Post, four hundred miles away. He did not know how long a journey he had, and he never made it home. He died from exposure, exhaustion, and hunger along the tracks that he thought would lead him to his family in October of 1966. Just a kid.

The Secret Path is a simple but searing portrait of the experience of children in Canada’s residential schools. From the late nineteenth century into the 1980s (Cecilia Jeffrey closed in 1974), Downie wrote,

“All of those Governments, and all of those Churches, for all of those years, misused themselves. They hurt many children. They broke up many families. They erased entire communities. It will take seven generations to fix this. Seven. Seven is not arbitrary. This is far from over. Things up north have never been harder. Canada is not Canada. We are not the country we think we are. “

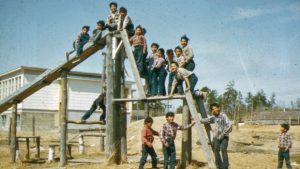

Children at Cecilia Jeffrey were subjected to medical “experimentation and treatment of ear disease” in the 1950s, government documents later revealed. Children suffered, emotionally and physically.  Their families did, too, and a lot of people knew about it. If you are interested in this history, or the parallel history of boarding schools in the United States, you should watch the film, listen to Downie’s music, and learn from the panel discussion treating the painful legacy of these institutions, filled with children taken by law from their parents aboard “Trains of Tears” which transported them hundreds of miles from their homes. Between 20,000 and 50,000 children were sent to residential schools in Canada. As in other parts of the history of native peoples, the numbers can stagger, become too abstract. What Downie does so well is force us to look at the entire broken and horrible process from the perspective of one child.

Their families did, too, and a lot of people knew about it. If you are interested in this history, or the parallel history of boarding schools in the United States, you should watch the film, listen to Downie’s music, and learn from the panel discussion treating the painful legacy of these institutions, filled with children taken by law from their parents aboard “Trains of Tears” which transported them hundreds of miles from their homes. Between 20,000 and 50,000 children were sent to residential schools in Canada. As in other parts of the history of native peoples, the numbers can stagger, become too abstract. What Downie does so well is force us to look at the entire broken and horrible process from the perspective of one child.

There is a large literature on the history of American Indian boarding schools. The bibliography will guide you to some of the books I like. The best treatment of the famous Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania remains the unpublished dissertation written by Genevieve Bell, “Telling Stories out of School: Remembering the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, 1879-1918,” (Ph.D diss., Stanford University, 1998). You will likely have to get it through your college library’s interlibrary loan.

Bell showed that we have not told the story of the American boarding schools as effectively as we might, that the important insights from this vast scholarship have not trickled down to high school and college American history textbooks. For one thing, we have allowed Richard Henry Pratt, the founder of Carlisle, to shape too much of the narrative. Pratt liked to boast that he would “kill the Indian and save the man.” He liked to produce before-and-after pictures, showing “savage” children from the western wilds and the same children, cleaned up and with their hair cut, in the military uniforms worn by Carlisle students. Pratt wanted his supporters to believe that he was “civilizing”

wild Indians.

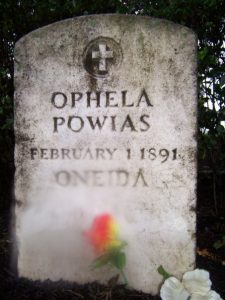

The reality was more complex, a point Bell makes convincingly. The most numerous children at Carlisle came from native communities in the east–Oneidas, for instance, or eastern Cherokee. These children spoke English and already were familiar with agricultural work on a white American model. Many of them already were Christian. They studied Latin and Trigonometry. Many of them wrote English beautifully.

But the institutions still were cruel. Institutions in general where “the other” was corrected, improved, educated, reformed, rehabilitated, or detained, were routinely brutal. Children died at these schools, far from home, some without knowing how much their parents and siblings missed them, without knowing how much they were loved.

I took this picture on a very rainy day nearly a decade ago in the graveyard that still stands on the site of the former Carlisle Indian School. I was inspired to visit the site one day while I was in the area after reading Calvin Luther Martin’s The Way of the Human Being, which I mentioned in my previous post. In that book’s closing pages, Martin and his wife visited the graveyard at Carlisle. Having left his teaching job at Rutgers, and having spent some time teaching the real people in Alaska, Martin looked at the columns and rows of tombstones as if they were the seats in a classroom. He presented to them, in a sense, his last lecture.

I took this picture on a very rainy day nearly a decade ago in the graveyard that still stands on the site of the former Carlisle Indian School. I was inspired to visit the site one day while I was in the area after reading Calvin Luther Martin’s The Way of the Human Being, which I mentioned in my previous post. In that book’s closing pages, Martin and his wife visited the graveyard at Carlisle. Having left his teaching job at Rutgers, and having spent some time teaching the real people in Alaska, Martin looked at the columns and rows of tombstones as if they were the seats in a classroom. He presented to them, in a sense, his last lecture.

“I took my position at the front of the class and looked around, professor for the last time. Before me, attentive students in silent formation. The last class at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. They died before becoming blacksmiths and carpenters, shoemakers and tinsmiths, tailors, printers, harnessmakers, plumbers, bricklayers, or laundresses, cooks, and seamstresses. But they were already real people, I thought, as I fought back my anger–people who understood the way of the human being in this place. I was a man, a historian, standing before a cemetery created by blundering good will.

I paused and reconsidered. I had to leave them with something more satisfying than my bitterness. . . I apologized to these kids. I apologized not as an angry historian but simply as a sorrowful human being. What else can one possibly be, standing in a graveyard? I called some by name as I did so. I told them we were traveling west, and I invited any lingering spirits to come along. All I heard were the cars, though sometimes, more powerfully, the wind.”

The United States, several years ago, apologized for its historic treatment of native peoples. You probably missed it. The apology received little attention. Largely the work of then-Senator Sam Brownback, a Kansas Republican, the resolution included the formal “Whereas” statements that appear so often in Senate documents: Indians had been treated badly, they had been dispossessed, and, “Whereas the United States government condemned the traditions, beliefs, and customs of Native Peoples, and endeavored to assimilate them by such policies as the redistribution of land under the General Allotment Act of 1887, and the forcible removal of Native children from their families to faraway boarding schools where their Native practices and languages were degraded and forbidden,” the United States apologized “to all Native Peoples for the many instances of violence, maltreatment and neglect inflicted on Native Peoples by citizens of the United States.” Nonetheless, “nothing in this joint resolution,” the Senators agreed, “authorizes or supports any claim against the United States.”

It was an empty, cynical, and shallow gesture. We do not talk about the boarding schools, and other painful parts of our history, frankly enough. We do not learn from this history. The government boarding schools are gone, but there are still a few run by church and other organizations, like St. Labre in Montana. Their approach is different than those used in an earlier period but, still, it is important to remember how recent this history is. The Thomas Indian School on the Cattaraugus reservation in western New York remained open into the 1950s. It is not unusual to speak of and, in New York State, to meet boarding school “survivors.”

Canada is doing more than the United States to talk about its troubled past. Still, problems remain. Just a couple of days ago, APTN ran a story with the headline “Ontario Government Has No Idea How Many First Nations Kids it Puts in Group Homes.” Three teenage girls had died in these schools in less than six months, one in a fire, two by suicide. If American officials and Canadian officials would have had their way in the not-so-distant past, nobody would be discussing the fate of Indian children, for the schools would have succeeded in assimilating native children into the Canadian or American mainstream. According to Ry Moran, the director of the Canadian National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation at the University of Manitoba, these schools “tried to end indigenous peoples. They tried to end cultures.” Speaking at a panel discussion available on The Secret Path website, Moran noted that “the railways were used in this country to establish Canada, but they also were used to transport kids,” many thousands of them, who were forcibly taken from their families. It’s a story, Moran argues, that still too few Canadians know. (The National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation is creating an archive, an amazing but troubling archive of arrogance, cultural imperialism, and ethnocentrism: You can check it out right here).

Americans, too, do not know these stories well enough. Colonialism. It is a force. It produces comforting myths that blind Americans to the truth. “It could not have been as bad as we might have heard.” I have heard that from audiences where I have spoken. We do not like to confront the legacy of our past cruelties. More powerful work like that produced by Downie may force more of us to do so.