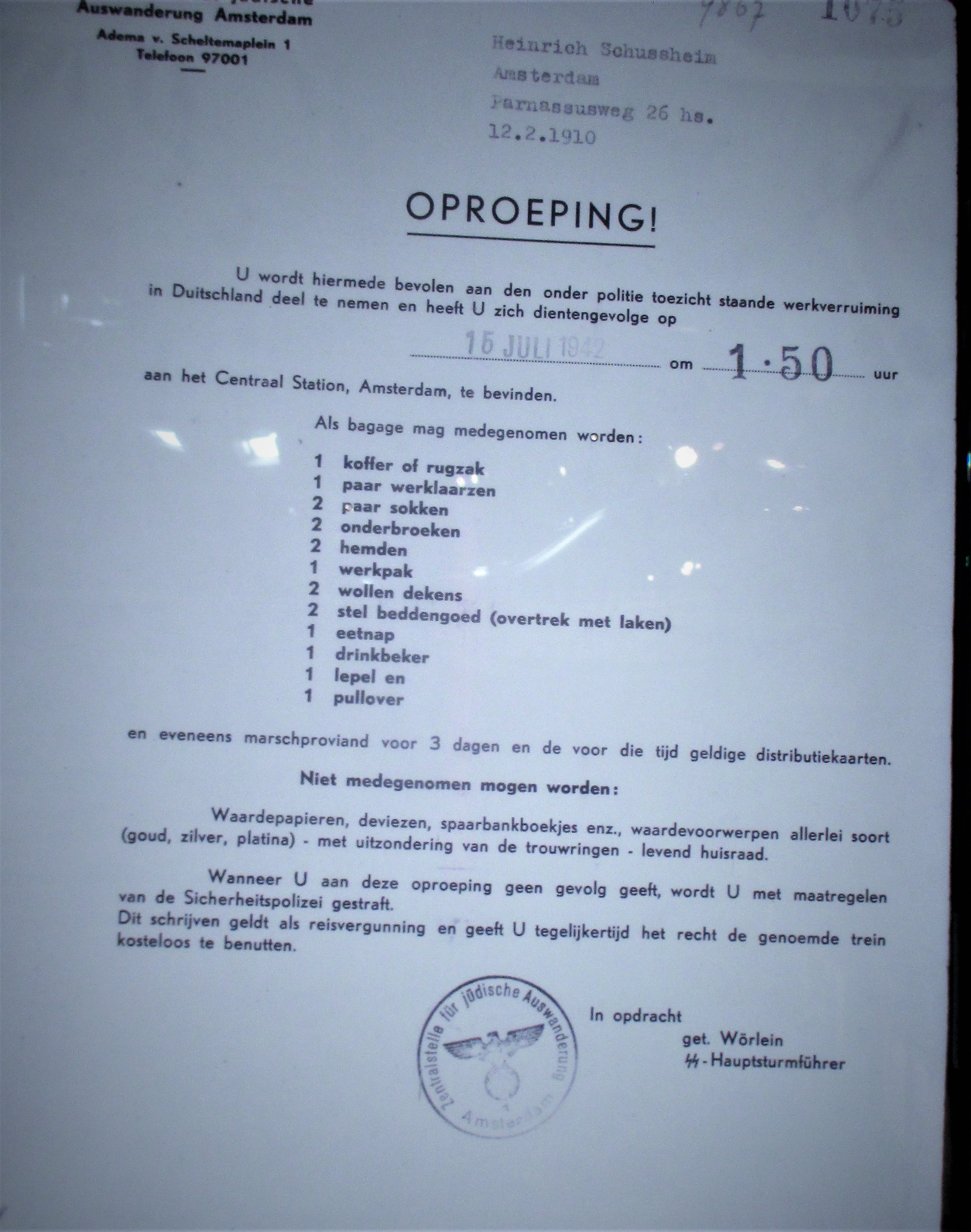

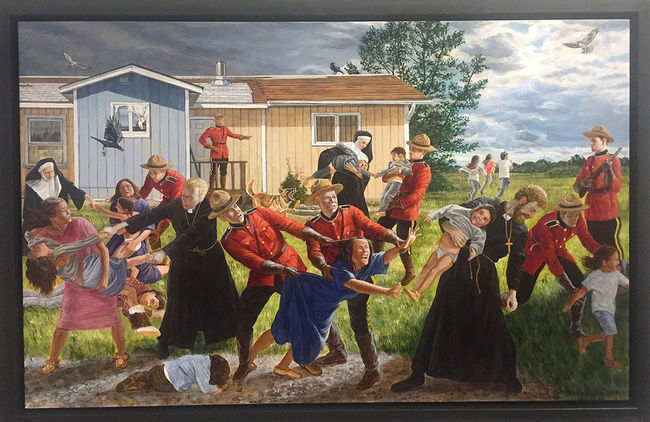

In Amsterdam last week I visited the Dutch Resistance Museum, dedicated to chronicling the history of the German occupation of Amsterdam, the Holocaust in the Netherlands, and those courageous citizens who chose to resist. The Nazis deported 107,000 Dutch Jews to labor camps. Only 5500 survived.

It was a wrenching museum experience. It must be especially so for those who lost family and friends in the Holocaust. I visited on the Friday of a week in which the President of the United States told four women of color who serve in Congress to go back to where they came from. All four of them were American citizens. When the President spoke at a “rally” in North Carolina the crowd eagerly and enthusiastically followed his racist lead. “Send her back,” they chanted, about a US Representative who migrated to the United States as a child and has been a citizen longer than the President’s wife. We have no need, the President said, for people who hate America, who criticize me in “disgusting terms.” Love it or leave it. Criticism is unwelcome. It is easy and intellectually lazy to make facile comparisons between President Trump’s America and Nazi Germany, but there can be no denying the rhetorical similarities. The President and his supporters parroted in their chants and howls the excesses of the Nazis and their sympathizers. All this was abundantly clear from looking at the exhibits at the Dutch Resistance Museum.

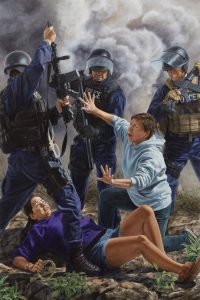

I am not one of those who is surprised and disappointed by Donald Trump. This is precisely what I expected from him, what he has shown himself to be. I am disappointed, but not surprised, that significant numbers of people have no problem with his many well-documented faults, who will bend themselves over backwards to defend him. Completely abdicating any sort of critical thought, or empathy, and ignoring entirely the obligations of informed citizenship, they march along merrily towards despotism. Ignorant of the traditions and history of American constitutionalism, by the tens of millions they roar their support for this tyrant, egged on by a well-oiled propaganda machine that promotes as it shapes this President. Meanwhile, fearful of the backlash that followed Hillary Clinton’s apt description of Trump’s followers as “deplorables,” Democrats offer tepid resistance that thus far does not extend to a concerted effort to remove him from office for high crimes and misdemeanors, including obstruction of justice, violations of the emoluments clause, and allegations of rape. He has assembled an unholy alliance of corporate elites, grifters, racists, and creeps, unopposed effectively by a timorous Democratic party leadership that should call its supporters out into the streets. Any reflection on the history presented in Amsterdam makes clear that we are not doing enough to counter his policies, and the tens of millions of Americans who continue to embrace his racist and cruel policies. I find it difficult to laugh at the many people who make fun of this president, and the crazy things his supporters say. No, I think now. They are dangerous.

I refuse to believe that our current crisis is not a product, in some small part, of assaults on the teaching of history and the liberal arts generally–fields that emphasize to students the importance of questioning and analyzing sources, investigating and researching deeply, and reading and thinking critically. True, the bulk of Trump’s support comes from non-college educated Americans. “I love the poorly-educated,” he once said. But it seems to me that he does not want you to think. You do not need to see or hear the evidence, he says, whether the unredacted Mueller Report or his tax returns or the testimony of cabinet officials lawfully subpoenaed by Congress. You must not question him.

I am teaching my Humanities class in Oxford this summer. We take our cue from Pericles and discuss how the purpose of government is to secure the commonwealth, the good of the whole. That requires that American citizens exercise what the Revolutionary generation saw as “virtue”: the ability to set aside one’s self-interest for the good of the community. Corruption, in this sense, is virtue’s opposite. In order to exercise this virtue, citizens must be independent, able to exercise their will freely, and they must be active, engaged, and informed. Those who are ill-informed, and constitutionally illiterate, and who do not think and reason about the way things are and the way things ought to be, make perfect tools for a tyrant. A citizen, for instance, who knows nothing of the language of Article II of the United States Constitution is unlikely to challenge the president’s spurious and frightening claim that it gives him “the right to do whatever I want.”

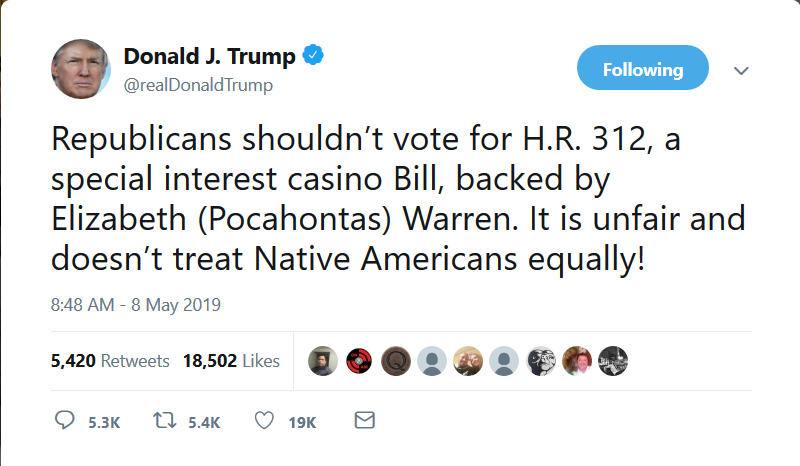

Evidence of this assault on engaged citizenship, and the kind of education that promotes it, is visible everywhere you look. The conservative Republican governor of Alaska has effectively shit-canned his state’s higher education system. Ted Cruz, that Texas Senator who combines sadism with unctuousness, has proposed legislation to label the activists in “Antifa” as a terrorist organization, while white supremacists and nationalists continue to regularly gun down ordinary Americans with their military hardware. Scott Walker, the former governor of Wisconsin who with his allies in that state eviscerated its flagship university system, has been placed by President Trump on the board of the Smithsonian’s Woodrow Wilson Foundation. The Wilson Center is non-partisan and highly-regarded, while Walker has railed against “the absolute crap taking place on college campuses across the country.” So strongly does Walker oppose the teaching of critical thinking and research on college campuses that he included in this tweet, in all caps, “I AM PROUD TO BE AN AMERICAN,” with a large American flag, four tiny American flags, and four statues of liberty (an ironic choice to be sure, given the Republicans’ penchant for caging children carried here by their asylum-seeking parents).

It is a common refrain. You hear it again and again and again. Liberals are corrupting the young. They are teaching “Socialist” and radical lessons in colleges and universities. The policies “radical socialist liberals” favor are dangerous and destructive, even though they are already in place in much of the western world. Liberals are “Un-American,” or “America-Haters” and, especially if they are people of color, they should go back to the “shit-hole countries” and other places they came from. And they teach history in a way that encourages students to hate their country.

These Republican charges are vile nonsense. Republicans want to silence dissent and impose their own white nationalist views of the majority of Americans who find them repellent, even if that means controlling the media, restricting the right to vote, and incarcerating ever growing numbers of Americans. We who educate do not need to become activists. Always we must remember the canons of our discipline. But nevertheless, in the course of doing our jobs as we ought, we will resist and challenge these policies. If truth has a liberal bias, as Stephen Colbert once joked, history shows these Republican operatives for what they are: a grave threat to the Constitution. That tens of millions of Americans continue to support these policies, despite all they might have seen and heard if they kept their eyes and ears open, demonstrates the magnitude of the threat we face. It is a challenge we can and must confront. Our job is, as I have written on this blog, to promote intellectual courage, so that our students will ask probing and important questions, dig relentlessly for answers, and assess carefully and critically what they see and hear. Courageous thinkers will challenge the assertions of those with power. They will demand of them the evidence that supports their reasoning. They will not accept pat answers, slogans, and sound bites. Because they call those in power to account, they are seen as a threat. And, time and again, Republicans have acted on that threat. As historians, most assuredly we can say we have seen this before.