Specifically, of what value is the Pope’s “heartfelt” apology to Canada’s First Nations about the treatment they received in residential schools across much of the twentieth century?

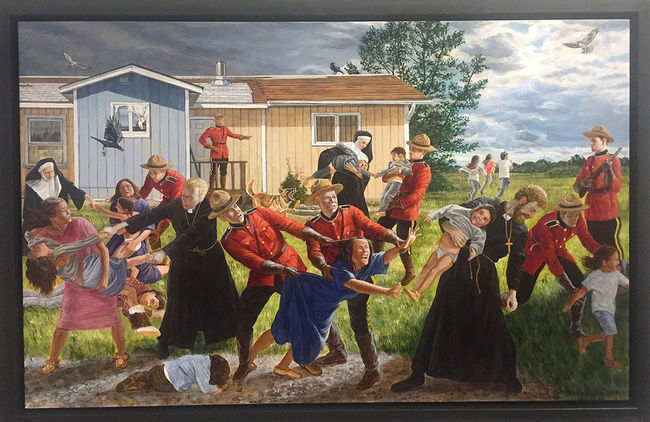

At one level, it is not a question for me to answer. I write from the privileged position of a scholar who never had to experience that which generations of Indigenous Canadians have had to live through, and continue to live with. The legacies of Canada’s system of residential schools, supported and enforced by the Catholic Church and other major Protestant denominations is clearly visible. The resources for learning this history are increasing in number and becoming more accessible to non-Indigenous audiences every day. Connie Walker’s fantastic journalism is just one of many examples.

I do not think there is any doubt about the significance of what the Pope did yesterday. Hobbled by sciatica and other ailments that have limited his mobility, the Pope visited the site of a residential school at Maskwacis, Alberta, yesterday, and issued a formal apology to the members of the commuity. (A full video of the gathering is available here.)

Pope Francis spoke of his visit as the first stop on what he called a “penitential pilgrimage.” He traveled, he said, to the community “to tell you in person of my sorrow, to implore God’s forgiveness, healing and reconciliation.” He acknowledged their long-standing ties to the land, their stewardship of the land. He acknowledged the trauma the community had experienced, and that his words might cause individual members of the community great pain. He quoted Elie Wiesel: “The opposite of love is not hatred, it’s indifference.” He hoped that the world would watch and learn from his apology, and that this was the first step in an effort to make the world a better place for all who have suffered.

“I am here because the fist step of my penitential pilgrimage among you is that of again asking forgiveness, of telling you once more that I am deeply sorry. Sorry for the ways in which, regrettably, many Christians supported the colonizing mentality of the powers that oppressed the Indigenous peoples. I am sorry. I ask forgiveness, in particular, for the ways in which many members of the Church and of religions communities co-operated, not least through their indifference, in projects of cultural destruction and forced assimilation promoted by the governments of that time, which culminated in the system of residential schools”

“Although Christian charity was not absent, and there were many outstanding instances of devotion and care for children, the overall effects of the policies linked to the residential schools were catastrophic.” He knew, he said, that these policies were a mistake, one incompatible with the Gospel. It was a “great evil.”

The Pope wished to reaffirm this point, “with shame and unambiguously. I humbly beg forgiveness for the evil committed by so many Christians against the Indigenous peoples.” But begging pardon, he said, was only a first step. The Catholic Church must “conduct a serious investigation into the facts of what took place in the past and to assist the survivors of the residential schools to experience healing from the traumas they suffered.”

It was a good statement. It was far superior to the legalistic apologies the United States has enacted from time to time. It is difficult to imagine what more the Pope might have said. Some members of the audience were visibly moved by the Pope’s apology. They had waited a long time, but at long last, the Pope had made the journey to their homelands to apologize in person. Francis said that he could not visit all the communities that had invited him. Still, some clearly appreciated his visit.

Others expressed some skepticism. An apology without action was meaningless, and they wanted to see what action followed before they passed further judgment. Some wished that the Pope would have renounced the discovery doctrine, by which the Catholic powers claimed in the late fifteenth century their lands in the Americas. Deeds, they argued, were more important than the colonizers’ words.

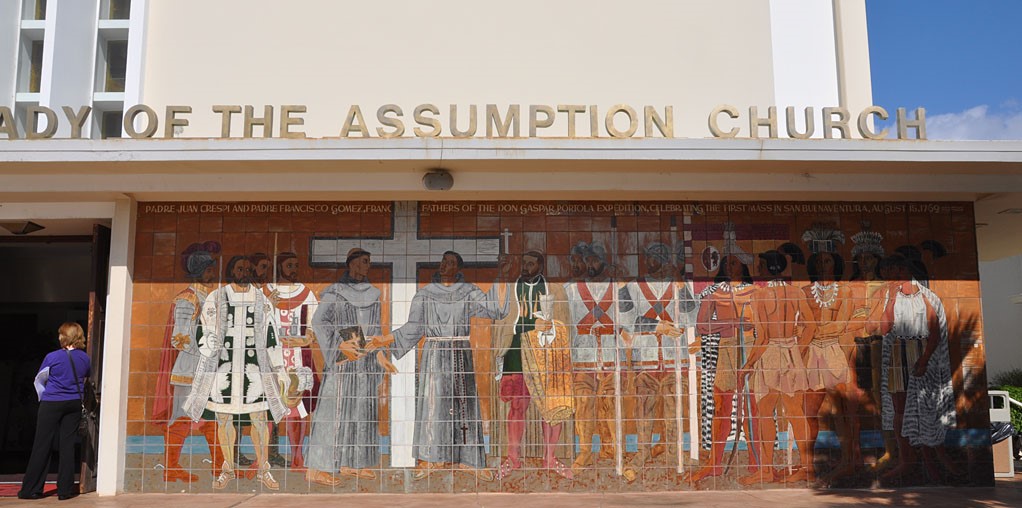

That is entirely fair. Indigenous peoples have listened to those who speak for government agencies and missionary organizations talk a good game, but they have reason to be suspicious. Look on Twitter, and you could detect the clenched reception to news that the missionary Will Graham, one of Billy’s grandsons, was going to preach on reservation’s across South Dakota. So much damage has been done by those who carried the Bible into Indian Country.

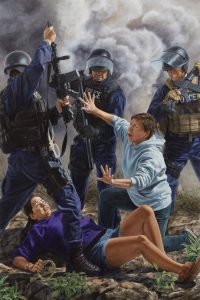

There is in the United States a substantial number of people who do not like to hear about the negative parts of US history. I am willing to bet that the same is true in Canada, as well. I have heard this sentiment a lot over the years, and it takes different forms: discussion of the negative parts of history is unpatriotic, or demoralizing, or depressing; telling these stories might come at the expense of telling more positive and uplifting stories that could bring young people to respect and revere American institutions; or, occasionally, telling the stories of those individuals and groups who have fallen by the wayside or who suffered as a result of American progress somehow diminishes the dominant narrative and those white people who populate and benefit from it. These reactionary forces are powerful. Those who bring these stories up can expect to be criticized severely, to have their integrity and their objectivity as scholars questioned, or to be dismissed with that empty-headed epithet that their work is “politically correct.” I saw this first hand when I taught in Montana at the beginning of my career in the 1990s. Speaking out on these issues, it turned out, nearly cost me my job.

The Pope’s apology is a limited response. His words can be seen as those of the Church he leads, but also as an expression of sorrow from a single man who has learned from this blighted hellscape of a story and wishes in some small way to try to set things right, to assuage the grief, to comfort those injured. The Pope’s apology, I hope, will open up dialogue and discussion. That discussion is needed badly in Canada, and even more so in the United States.

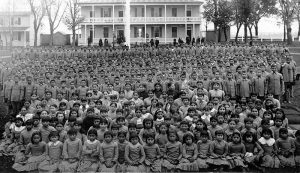

Both nations continue to deal with the unaddressed problem of missing and murdered indigenous women, and the deep structural problems that gave rise to the Idle No More movement, has undertaken efforts to talk about its painful past. I have mentioned on this blog the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation housed in Manitoba: it is a marvelous project that might equip Canadians to tell the story of Canada’s residential schools, the young people taken by law and by the authorities from their families to be educated, and the consequences and legacies of these wrong-headed and evil policies.

In the United States, in places, there are efforts to begin an accounting for the nation’s past misdeeds. Confederate memorials are coming down. Some buildings, on some college campuses, named after racist and cruel figures from the American past, are being renamed, though not without controversy. Some universities with ties to the slave trade, like Brown and Georgetown, have undertaken programs to atone for their sins. President Biden’s Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland is looking into the legacy of boarding schools in the United States.

But when it comes to native peoples, we are way behind Canada and Australia. Small gestures, no doubt, are taking place: some members of some religious congregations have pushed their churches to renounce the so-called “doctrine of discovery,” a symbolic gesture that in the end would cost these churches little. More real, perhaps, was the decision by the Society of Jesus several years ago to return land given to it by the United States on the Rosebud Reservation to the community. But a larger accounting has not occurred.

And without such an accounting, young people can only with great difficulty arrive at an understanding of the moral complexities of their nation’s past. We need more than an apology, couched in legalese, that nobody knows about. I have mentioned the congressional apology on this blog. You can read it here, and see how truly deficient a document it is. It is as if a Senate staffer went through an American history textbook, found the points where bad things happened to native peoples, and cobbled them together into a tepid and half-baked statement of regret. We are sorry, but want it understood that nothing in this apology opens us up to suit.

The resources to write and teach this history are out there, and contrary to what you might have been taught, native voices are not hard to find in the historical record. In the Agency records housed at the National Archives, for instance, hundreds and hundreds of reels of microfilm, each containing hundreds of pages of documents, allow committed researchers to reconstruct the government’s systematic programs to incarcerate native peoples on reservations, Christianize and civilize them, and take their land, all in the name of “Progress.” Scattered around the country in state, local, and organizational archives are the historical documents that reveal the herculean efforts of native peoples to survive these policies. In these records are the stories of native peoples who lived their lives under this oppressive regime. Their stories are worth talking about. Obviously if I did not believe this very strongly I never would have written Native America. We need to know these stories, for without comprehending the damage done we can hardly understand that for which we apologize. And without apologies, we cannot even begin to show repentance for the crimes of the past. The Pope has apologized in Canada. I hope it is followed by action, both in Canada and the United States.