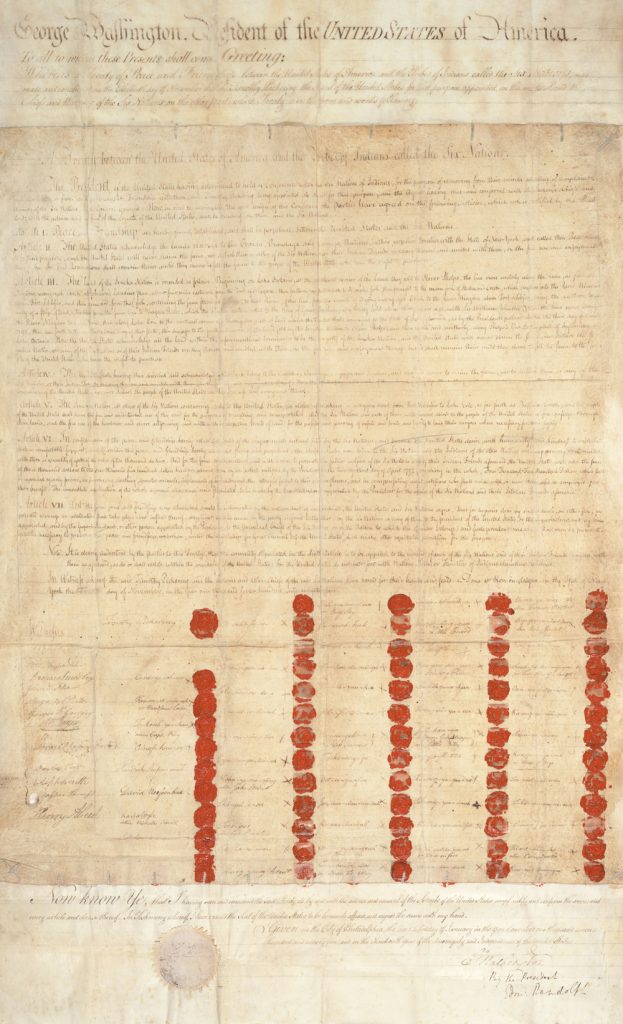

In November of 1794, the six Iroquois Nations entered into a treaty at Canandaigua with the United States that recognized their Nations’ right to the “free use and enjoyment” of their lands. That phrase is used three times in the treaty, thus making it central to the entire diplomatic accord. In exchange for a promise that they would never join with those Indigenous peoples who had warred against the United States, and a specific grant of permission allowing citizens of the United States to pass through their lands “for the purposes of travelling and transportation,” the Six Nations were guaranteed an annuity of $4500, the return of lands along the Niagara River that they had ceded a decade before, and the recognition of their sovereignty and nationhood: the free use and enjoyment of their lands.

There are two principles I would like you to understand before we go any farther, one derived from the American constitutionalism, and the other from the history, culture, and traditions of the Haudenosaunee. For the first, I will have you think for a second about what the United States constitution says about the rights of Indigenous peoples. There is the Supremacy Clause, of course, which states that treaties and acts of congress are the “supreme law of the land.” That passage does not specifically mention Indigenous peoples, but its relevance should be clear enough. There is also the passage in Article I, Section 8, through which “we the people” granted to the Congress the right to “regulate commerce” with the Indian tribes. We call this the Indian Commerce Clause.

The language in the Constitution, my students find when they read it for the first time in their lives, is brief, skeletal. It was left up to the first federal congress to enact the legislation necessary and proper to carry these constitutional provisions into effect. In 1790, Congress passed into law the first of several federal Trade and Intercourse Acts. The law was revised periodically between 1790 and 1834, but one principle remained clear: The United States claimed no real authority over what was coming to be referred to as “Indian Country.” The Trade and Intercourse Acts regulated the conduct of white people, not Indians. You want to trade with an Indian? You need a license from a federal agent. If you want to purchase land, the negotiations must be overseen by the United States and resulting agreement ratified by a two-third vote of the United States senate. Without that approval and oversight, the sale was null and void. The United States worked to regulate the conduct of its own citizens. It claimed no authority over the internal workings of Indigenous nations.

The second principle goes by the name Guswenta, and it is represented by the Two-Row Wampum. Parallel lines that do not cross, the lines represent a European ship and an Indigenous canoe. They travel the same river, and share the same space, yet the lines never cross. Non-interference, independence, and autonomy: You do not dictate to us, the Iroquois might have said, and we will exercise no authority over you. Guswenta, originally a generic word representing a belt of wampum, came to be applied to this specific belt which justly reflected the cardinal values of Haudenosaunee diplomats.

So, to come back to the Treaty of Canandaigua, we have an agreement recognizing an Indigenous right to the “free use and enjoyment” of the land that is consistent with both these formulations. Think of it this way: You have a sheet of white paper in front of you. That white sheet represents all the land from the Genesee River west to the Niagara River and Lake Erie, and from Lake Ontario in the north to the boundary of Pennsylvania. In that vast tract, the Senecas can do what they want. Americans had no power there save for whatever the Senecas gave to them, and in this treaty, that grant to the Americans is pretty limited. Free use and enjoyment: keep thinking about what that means.

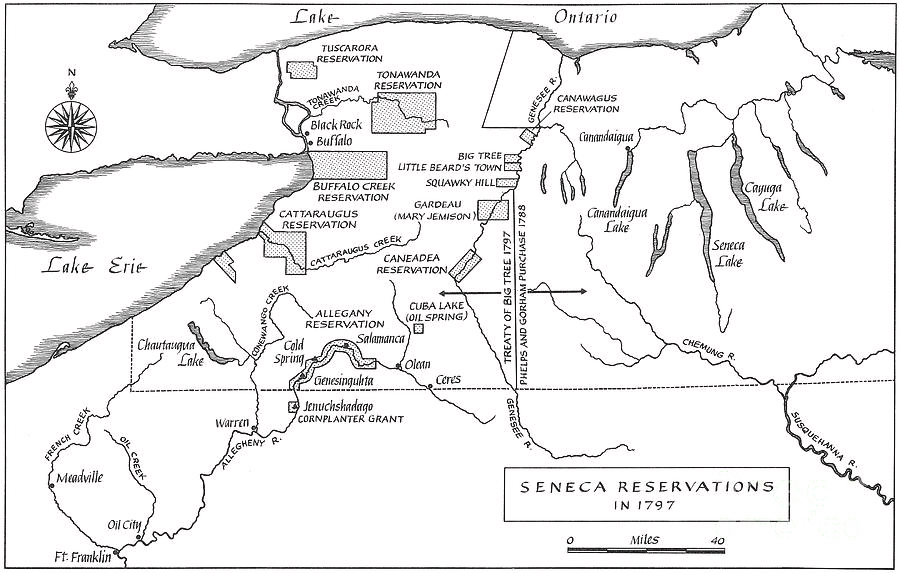

Despite Canandaigua, settlers, and more importantly land developers, coveted the rich, dark soil of western New York. The Senecas numbered a bit over 2000 people, but there were many times that number of land-hungry Americans who wanted their land. They were ready to seize the opportunity. They were willing to come and ready to take it. So, in 1797, at Big Tree near today’s Geneseo, New York, the Senecas, the westernmost of the Six Iroquois Nations, entered into a treaty with Robert Morris and his son Thomas, overseen by a federal agent in accord with federal law.

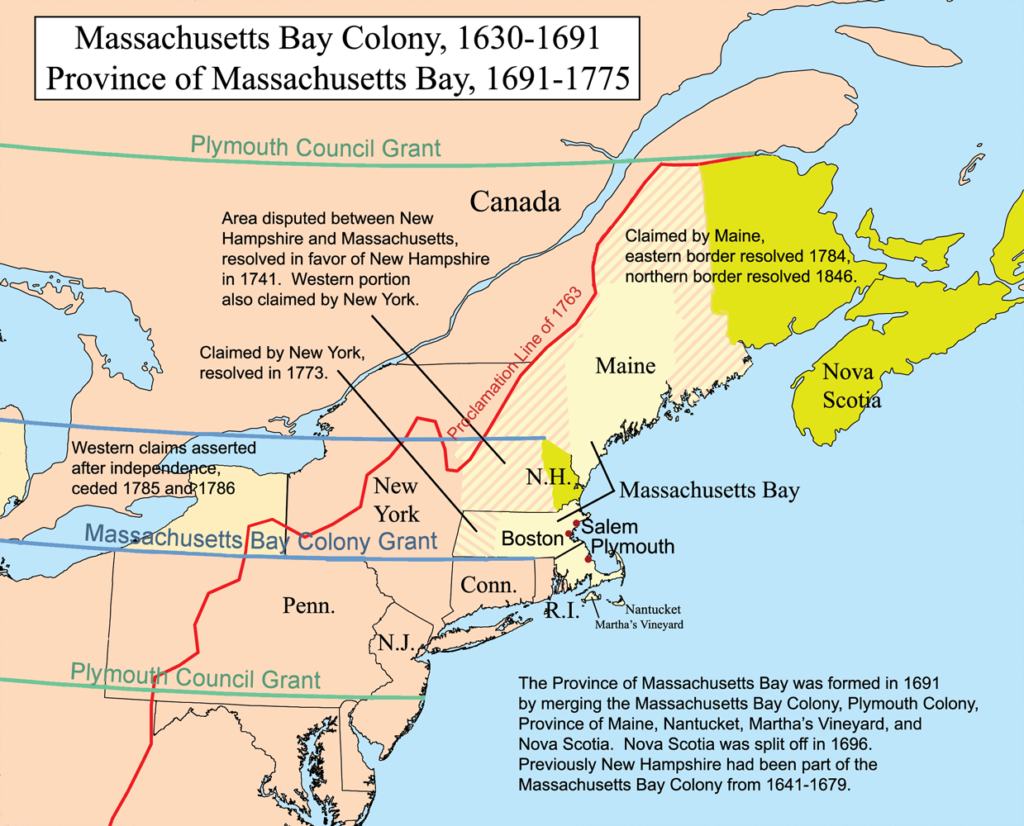

A little background is in order here. First of all, much of New York was claimed by Massachusetts, the colonial charter of which specified its northern and southern bounds but not its western. So, if you drew those northern and southern lines across the continent westward you can envision the breadth of Massachusetts’ claim. (The state of Connecticut claimed a chunk of northern Pennsylvania for similar reasons). Massachusetts and New York worked out an agreement in Hartford in 1786 which gave New York jurisdiction over the disputed territory, and to Massachusetts the right of preemption. Preemption was essentially the right to first purchase of the land, a type of title that might sit dormant until the Indians’ right of occupancy was extinguished. Massachusetts emerged from the Hartford agreement positioned to tell the Iroquois that because of our preemption rights, you can only sell your lands to us.

Claiming a preemption right over Indigenous land was consequential. It certainly had the practical effect of reducing the value of those lands by eliminating any other potential buyers. Preemption was based on notions that Europeans had a claim to indigenous land that needed only the removal of the Indians’ claim to become real. Europeans, the logic went, had title, and Indigenous peoples a right of occupancy. Where did this seemingly dotty notion come from? From the same place men of small imagination always have found justification for their awful beliefs. It’s called the “Doctrine of Discovery.” While more has been made of the Discovery Doctrine than I think is warranted, it derived from the Old Testament. Europeans owned title to the land because at the time they found it, Indigenous people were not making use of the land properly. Indigenous peoples did not break turf and twig, clear the land and plow it, and follow the Biblical command to make it fruitful. This is one reason depictions of Indigenous peoples as wanderers and hunters and nomads are not only factually incorrect, because they did plant crops and live in horticultural settlements, but pernicious as well.

Especially when preemption rights became something that could be bought and sold. Massachusetts sold its preemption rights to Oliver Phelps and Nathaniel Gorham. They acquired a lot of Haudenosaunee land east of the Genesee before their enterprise went belly up. Massachusetts foreclosed and sold the preemption right to the remaining lands to Robert Morris, widely considered the most important financial policy maker of the American Revolution. Morris hoped to sell these rights to the Holland Land Company, but before they would pay, they insisted that Morris eliminate the Indians’ right of occupancy. Morris was ill, so he sent his son Thomas to Big Tree, today’s Geneseo, to negotiate a treaty with the Senecas.

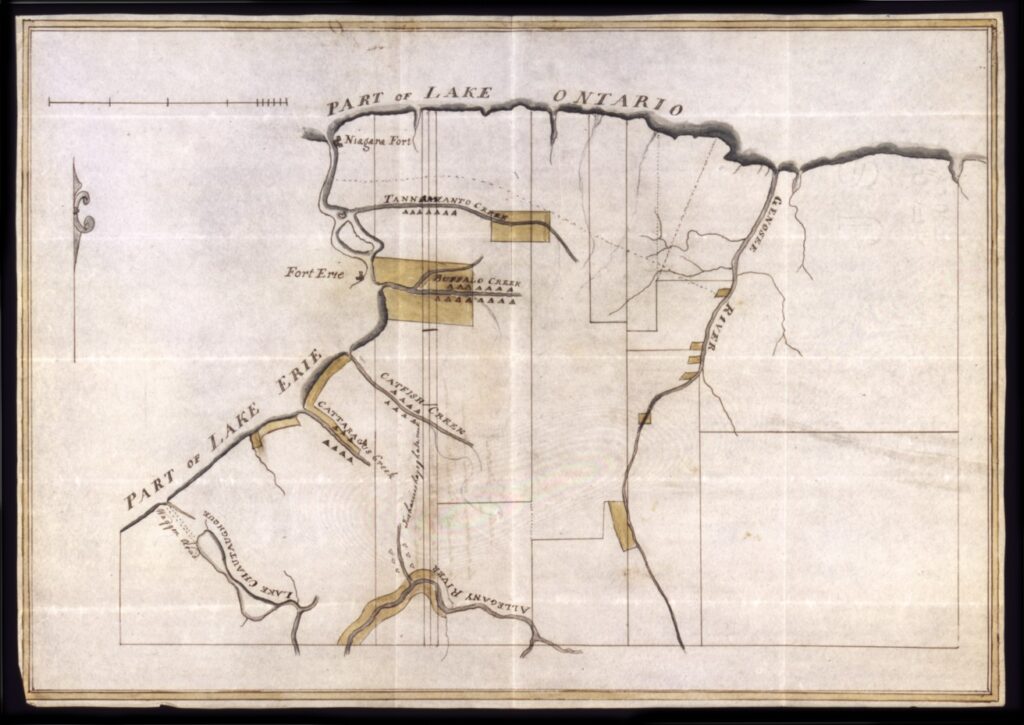

The Big Tree Treaty council was an ugly affair. Morris bribed people and dispensed alcohol freely. In the end, he emerged with a document that granted him ownership of all Seneca lands except for twelve reservations scattered throughout the western quarter of New York State. Come back to your piece of paper. Draw twelve circles on the paper. These can represent the twelve reservation defined in the Big Tree treaty. Everything not inside one of these circles, the treaty reads, the Senecas gave up to Robert Morris in exchange for the annual payment of the interest on a $100,000 investment in stock in the Bank of the United States.

Why would the Senecas do this? Some historians have emphasized the bribes and the alcohol. There can be no denying how important these were to accomplish the treaty. But I would suggest you look at it another way. Tens of thousands of Americans were on the move westward. A handful of Senecas stood in the way. The Senecas could not halt the onslaught. The Sullivan-Clinton campaign of 1779, a military invasion of their homelands, taught them the price of resistance. They faced a dilemma. They could receive something for their land or lose these lands outright to the men who were coming to take them. The Senecas met the Americans with limited bargaining power.

But think about this: In the “Rough Memoranda of the Treaty of Big Tree,” a record of the proceedings housed in the O’Reilly Papers at the New York Historical Society, Thomas Morris told the Senecas that if they agreed to sell their lands, that we the purchasers “do not mean that you should all rise from your seats and abandon your villages but that you should relinquish that part which is totally unproductive to you, reserving to yourselves in and about your different settlements only as much is necessary for your actual occupation.” The dozen circles that I asked you to draw on that page: each one of them was a settlement site, a Seneca town, of cultural and historical significance to them and that they reserved for their own exclusive use.

The Senecas made good use of this land. They reoccupied much of what they had fled from during the Revolution. In October of 1791, the missionary Samuel Kirkland completed a census of the Iroquois. For the Senecas residing on the west side of the Genesee River, he mentioned “six small villages.” “Kanawages—about 20 miles south of Lake Ontario containing 14 wigwams—Oahgwataiyegh alias hot-bread their chief. 112 lived there. 120 people were at Big Tree’s town, “about 8 miles farther south, containing 15 houses. Big tree, alias Kaondowanea their chief.” “Little Beard’s town, about five miles south and on the great flatts—containing 14 wigwams.” 112 people lived there. Also, “the town upon the hill, about 3 miles south & near the forks of the Genesee River—containing 26 houses, under the direction of Big Tree & Little Beard.” 208 lived there. There was also “Onondaough 12 miles southwardly lyong on the west branch of the Genesee—6 houses–& under the direction of Big Tree & Little Beard.” 48 lived there. Finally there was “Haloughyatilong—12 miles farther south–& on the forementioned branch containing 22 houses.” Population here was 176. Furthermore, there were 25 houses of Tuscaroras with a population of 208 living near Big Tree. This would be the site of Ohagi.

Meanwhile, there were 2048 Senecas, Onondagas, and Cayugas residing on Buffalo Creek. Francois-Alexandere-Frederic La Rochefoucauld-Liancourt, a French observer who traveled through “the Country of the Iroquois” in 1795, visited the towns that would be recognized as Seneca ground in the Big Tree Treaty. Rochefoucauld-Liancourt visited Canawaugus, where an “Indian, who speaks French, is waiting for us.” At “Captain Watsworth’s” in Geneseo, uphill from Little Beard’s Town and Big Tree, he and his companions noticed how “several parts of the forest have been burnt down by the Indians, who possessed this country from time immemorial.” As he traveled, he said, “we frequently traced or met with Indian camps, as they are called, i.e. places where troops of them, who were either hunting or travelling, had passed the night.” Wadsworth’s house was a vile hole filled with noisome odors. Liancourt encountered Wadsworth “undergoing the operation of hair dressing by his negro woman,” after he “had just sold a barrel of whisky to an Indian.” Liancourt learned that the Indians were easy prey to unscrupulous traders. “A little whisky will bribe their chieftains to give their consent to the largest cessions; and these rich lands, this extensive tract of territory, will be bartered away, with the consent of all parties, for a few rings, a few handkerchiefs, some barrels of rum, and perhaps some money, which the unfortunate natives know not how to make use of, and which, by corrupting what little virtue is yet left among them, will, ere long, render them completely wretched.”

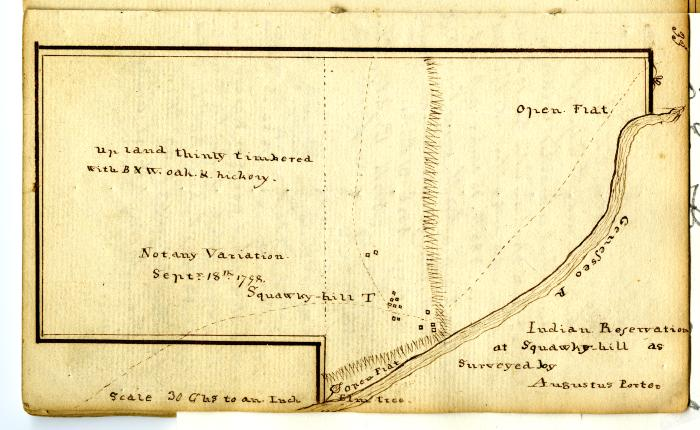

Liancourt traveled twelve miles and visited Squawky Hill and another Seneca village on “Mountmorris.” “They both contain Indian villages. That situate on the former height consists of about fifteen, and that seated on the latter of about four or five small log-houses, standing close together, roughly built, and overlaid with bark. In the inside appears a sort of room not floored; on the sides they construct shelves, covered with deer skins, which serve as their cabins or sleeping places. IN the midst of the room appears the hearth, and over it is an opening in the roof to let out the smoke.”

So back to the council at Big Tree. Thomas Morris resumed his speech . He said

“What then Brothers you may ask will be the advantages of your selling—I will tell you Brother. You will receive a larger sume of money than has ever yet been paid to you for your lands.. This money can be so disposed of that not only you but your children and your Children’s children can derive from it a lasting benefit. It can be placed in the Bank of the United States forever whence a sufficient income can annual be delivered by the President your Father to make you and your posterity forever, then the wants of your old and poor can be supplied and in times of scarcity, your nation can be fed and you will no longer experience the miseries resulting from nakedness and want. Brothers, the white people do not want your lands for the purpose of hunting but for that of cultivation—the Great Spirit has implanted in you a desire to pursue the beasts of the forest and in us to cultivate the soil. This cultivation, Brothers, does neither diminish nor destroy the Game, your hunting grounds will be of as much advantage to you in the hands of the white People as in your own, for you can reserve to yourselves the full and ample right of hunting over them forever. . . . .By selling your Lands therefore Brothers and reserving to yourselves the perpetual right of hunting on it then you retain every solid advantage for the comforts of life that which at present produces you nothing.”

In the actual text of the Big Tree treaty, 15 September 1797, we are told that the Senecas reserved for their exclusive use some lands, gave up others, “Excepting and reserving to them, the said parties of the first part and their heirs, the privilege of fishing and hunting on the said tract of land hereby intended to be conveyed.”

The US believed that by entering into this agreement, Morris had paid funds that extinguished the Indians’ right of possession. Morris had obtained the right of preemption from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and, with the Indians’ occupancy right paid for, the US believed that he was free to transfer that land to the Holland Land Company, which was better equipped than he to begin the complicated work of settling townships and overseeing its sale. Morris, the United States, Massachusetts and New York officials were remarkably consistent on this point and no significant disagreements existed.

Within a year of the treaty, Seneca women had complained that some of the reservations were too small. Speaking for the women in a 1798 council at Big Tree, Red Jacket said they were the owners of the land, “& now we are sorry our seats are so small, as we Women since the bargain it has given our minds much uneasiness to think our seats so small.” I think it is important to look into this, because clearly some Senecas wanted to renegotiate. In response to these demands, adjustments were made to the Tuscarora and Cattaraugus reservations. In 1801, Red Jacket made it abundantly clear that many of his followers had followed the advice of the United States. They expected, as a result of Canandaigua and the Big Tree annuity, “that we should be furnished with farming utensils for cultivating the ground & raise wheat & other grain—that we must have spinning wheels & learn our children to spin & knit—we were told we must make use of Cattle instead of moose, Elk etc & swine instead of beans, sheep, in place of dear, etc. etc.”

Red Jacket noted that “We finde ourselves in a situation which we believe our fore Fathers never thought of—instead of finding our game at our doors we are obliged to go to a great distance for it, & then finde it but scarce compared to what it us’d to be.” White people, Red Jacket continued, “are seated so thick over the Country that the dear have almost fled form us, and we finde ourselves obliged to pursue some other mode of getting our living, and are determined in all our Villages to take to husbandry, and for this purpose we want to be helped.” This is such an important insight: Red Jacket expected for his people to be able to draw subsistence from the lands they ceded, but now they found so many non-native people settling there that it had altered the game potential of the land. He complained of American violations of Big Tree.

So let’s take stock. You have your paper with 12 circles drawn on it. Imagine that you have shaded every inch of your page that is not one of those circles gray. Each of those circles is a Seneca reservation, in which there is no legitimate American right or claim to power to limit in any way the Senecas’ “free use and enjoyment of these lands.” Settlers, under the direction of the Holland Land Company, have access to everything not in a circle with one important exception. The Senecas retained the right to hunt and fish over the entire extent of the ceded lands. Everything you have shaded gray is territory these treaties guarantee to Seneca hunters.

Now, it is time for another Haudenosaunee concept, and that is the division of physical space into woods and clearings. These divisions, I suppose, can be drawn too starkly, but in general I believe they retain a great deal of value. Haudenosaunee people conceived of the world as divided into woods and clearings. Women exercised enormous influence in the clearings. This is where they gave birth, reared children, and planted and tended crops. It is here where the clan mothers would appoint the men who would lead their communities as sachems. Men’s realm was the woods. It was here where they hunted and, at times, fished. They passed through the woods to engage in warfare and take captives. If woman’s place in the cosmos was defined by the power to create life, men were life-sustaining killers as hunters and warriors. Indigenous communities claimed specific parts of the woods. These claims could be contested and fought over.

Here is the point: In the woods, men hunted, fished, and fought. Ownership was defined by use and use was defined by gender. To say that the men of an Indigenous community have the right to hunt and fish on certain lands, I hope you see, is analogous to saying that the community to which they belonged owns the land. It is possible to argue, then, that at Big Tree the Senecas obtained recognition of their right to the exclusive use of the clearings, where white people could not intrude and where Americans exercise no power and authority, and that they willingly would allow white settlers to share with them the woods. This helps us make sense of Red Jacket’s complaints a year after Big Tree about the Americans’ alteration of the gaming potential in the Woods and, a year later, Handsome Lake’s denunciation of land sales in the Gaiwiio, the new religion that the prophet Handsome Lake brought to the fore.

Twelve circles. Twelve towns. Twelve places that meant as much to the Senecas as any place has ever mattered to you. Buffalo Creek, Allegany, Tonawanda, Cattaraugus, Big Tree, Squawky Hill, Canawaugus, Gardeau. I could go on. I hope you drew those circles in pencil, because now we enter a period where we begin to erase the circles and shade that space they occupied gray: a strip along the Niagara River and Little Beard’s Town along the Genesee in 1802. Familiar themes appear in these cessions. The actual language of the 1802 mile strip treaty notes that the Senecas sold the land, but reserved “to themselves…the right and privilege of encamping their fishing parties on the beach of said river, for the purpose of fishing, which is the common right of both parties, and to be enjoyed without hindrance or interruption from either; and while there encamped, to use the drift-wood for fuel, bit not to trespass on or injure, the proprietor or proprietors of the adjacent lands.” They also reserved the right to cross on any ferries and any bridges to be built in the future without tolls.

You can erase two circles. Shade where they were gray.

Then we have the large sale of 1826. Again, a little background is in order. In the early 1800s, the Holland Land Company sold the preemption rights to the remaining Seneca reservations to an entity called the Ogden Land Company. To be clear, that means that the Holland Company sold to the Ogden Company the right to obtain all the land in the remaining circles you have drawn on the page. The Ogden Company operated essentially in two parts of the state: around the larger reservations in the west—Allegany, Cattaraugus, Buffalo Creek, and Tonawanda– and in the Genesee Valley, where the lands set aside at Big Tree in 1797 were much smaller. In the west, Senecas had forcefully resisted any attempt to purchase their lands. In the Genesee Valley, this resistance was more difficult to maintain. But owing to bribes paid out by Horatio Jones and Jellis Clute, and the pressure white squatters placed on Seneca lands in the Genesee Valley, by the middle of the 1820s, some there were willing to contemplate a sale of lands. Indeed, in 1823 in Moscow (today’s Leicester, NY), Mary Jemison ceded all but two square miles of the Gardeau Reservation to John Greig and Henry Gibson. Greig was an employee of the Ogden Land Company. The cession, acquired for $4286 (less than .30 an acre) was never submitted to the Senate for ratification.

How did this happen and how did Mary Jemison have the standing to make this sale? According to historian Larry Hauptman, in April of 1817 Micah Brooks and Thomas Clute successfully persuaded the New York State Legislature to pass a bill making Jemison a citizen of the State of New York and “confirming her title to the Gardeau Reservation. Four days after this bill was passed, according to Hauptman, in return for $3000 and a mortgage to secure $4286, the aged Jemison executed a deed of seven thousand acres on the east side of the reservation to the same Micah Brooks and Jellis Clute. At the urging of John Jemison, Mary’s son, Mary agreed, because of her advanced age and her inability to manage her property, to hire Thomas Clute as her guardian. In payment for his services Thomas Clute was given a great deal of land on the west side of the Gardeau Reservation. On August 24, 1817, Mary Jemison leased all of the remaining Gardeau reservation, except for four thousand acres and Thomas Clute’s lot, to Micah Brooks and Jellis Clute. Jemison’s words are revaling about this transaction: ‘Finding their [Brooks and Clute] title still incomplete, on account of the United States government and Seneca chiefs not having sanctioned my acts, they [Brooks and Clute] solicited me to renew the contract, and have the conveyance made to them in such a manner as that they should thereby be constituted sole proprietors of the soil.”

In the 1823 cession, the Senecas relinquished to Grieg and Gibson all but two square miles of the reservation, which would remain Seneca property “in as full and ample a manner, as if these presents had not been executed: together with all and singular the rights, privileges, hereditaments, and appurtenances, to the said hereby granted premises belonging or in anywise appertaining, and all the estate, right, title, and interest, whatsoever, of them the said parties of the first part, and of their nation, of, in, and to, the said tract of land above described.”

In February of 1824, Secretary of War Calhoun wrote to Jasper Parrish and informed him that the Gardeau purchase did not require Senate ratification “because it was ‘considered in the nature of a private contract [that] does not require the special ratification of the Government as in treaties between the Indians and the United States.” Calhoun believed that as a result, “there is nothing to prevent its execution by the parties concerned, as soon as they may think it proper.” Three years later, the commissioner of Indian affairs wrote the secretary of war, indicating that the Gardeau deed did not need Senate approval because it was “esteemed to be a useless ceremony; the President approving it only.”

All of this occurred before the 1826 treaty. In May of 1826, the House Committee on Indian Affairs published a report with the title, “To Hold a Treaty with the Seneca Indians.” In it, the House committee members claimed that most Senecas wanted to sell their lands, that they wanted to become “civilized” on an American model, and that a federal commissioner should be appointed by the president to negotiate with them. Oliver Forward, a Buffalo politician, was appointed federal commissioner.

The treaty council, which was held at Buffalo Creek, was something of a debacle. The treaty was signed at the end of August in 1826. In it the Senecas’ ceded all their lands along the Genesee to the Ogden Land Company. Furthermore, the size of the Buffalo Creek, Tonawanda, and Cattaraugus Reservations was reduced significantly as well. All told, the Seneca estate had been reduced by 86,887 acres, being, Forward said, “something more than one third of the lands they own in the western part of this state.”

In exchange for this enormous cession, the Ogden Company agreed to deliver over a sum of $48,260, “lawful money of the United States.” As with the Big Tree Treaty of 1797, most of these funds were invested, with the annual interest earned on the purchase price paid out to the Seneca. This annual payment, calculated at an interest rate of 6% per year, came to be known as the Greig and Gibson annuity. Although the treaty said nothing about it, the Ogden Company apparently agreed to pay as well certain life annuities to Seneca leaders who aided in the negotiation of the agreement. Ten Seneca leaders received payments each year totaling $460.00. Addressing concerns about these payments in a letter to Commissioner of Indian Affairs Thomas L. McKenney, Jasper Parrish said that the negotiations had “been conducted with perfect fairness, openness and propriety,” and that “no threats, or menaces, or bribes were made use of to my knowledge: but, as in every case of the kind, certain gratuities were made, after the conclusion of the treaty.” Only $43,050 was ever invested, leaving close to $5000.00 from the purchase price missing.

Some Senecas and their supporters immediately challenged and contested the legality and the morality of the treaty. They complained, while others sent petitions and memorials to Washington supporting the treaty. To sort all this out took some time. Those who signed the treaty, according to the author of the best account of the period, did so because they feared that if they did not sell, they would lose their lands outright to the squatters that nobody seemed able to control. Some of the chiefs who signed the treaty, moreover, believed that by doing so they would satisfy the Ogden Company’s voracious appetite for Seneca lands. They sold lands to avoid the prospect of removal to the west. They expected that after this cession, which they agreed to reluctantly, the Ogden Company would leave the Senecas in peace upon their remaining lands. The United States Senate finally voted on the treaty in late February of 1828 but the vote was a 20-20 tie. John C. Calhoun, now vice-president, was not in attendance to break the tie. The agreement thus did not receive the two-third vote required by the Constitution for ratification, but the Senators, apparently in an effort to clarify the reason for their vote, passed an unprecedented resolution that read that “by the refusal of the Senate to ratify the treaty with the Seneca Indians, it is not intended to express any disapprobation of the terms of the contract entered into by individuals who are parties to the contract, but merely to disclaim the necessity of an interference by the Senate with the subject matter.” Viewed by more than twenty senators as a private agreement between the Ogden investors and the Senecas, they apparently believed that no reason existed for them to interfere. So why vote? Makes no sense.

Protests from Red Jacket, from the Quakers, and from others continued, however, and they finally had an effect. President John Quincy Adams ordered his secretary of war to conduct an investigation. Richard Livingston undertook the task. He conducted his investigation, and found evidence of considerable corruption and fraud at the treaty council. According to Seneca informants, the interpreters at the council threatened the gathered Indians with removal if they refused to sell. Jasper Parrish, an employee of the United States in Indian affairs, reportedly offered bribes to certain Senecas in return for signatures. As a result, the flawed treaty was never resubmitted to the senate, and it never received proper ratification. Still, the damage had been done, and by doing nothing, the United States government in effect acquiesced in a fraudulent, unethical and illegal treaty that carved a huge gash of territory out of the Seneca estate.

If the Ogdens achieved their goals in the Genesee valley, they struggled in their efforts to acquire the four largest Seneca reservations. In an 1819 memorial that Thomas L. Ogden sent to President James Monroe, he referred to himself as the “proprietor” of the lands presently “occupied by the Remains of the Seneca Nation of Indians.” Ogden, four years before the Supreme Court’s decision in Johnson v. McIntosh, asserted that he was the titleholder to the remaining Seneca reservations in the state of New York, and the Indians mere occupants.

The Senecas did not share this view. Ogden wrote to Madison in the aftermath of Seneca refusals to sell their lands. Indeed the Senecas seemed uninterested in listening to the Ogden appeals to sell, and seem genuinely offended by the Ogden men. In the Memorial, Ogden seemed surprised that the Senecas asserted “an unqualified title to the lands they occupy.” To prove their points, the Senecas produced their copy of the Treaty of Canandaigua, and cited it as evidence of their title to their lands.

The Ogden Company’s position had supporters within the United States government. Shortly after Ogden’s memorial, Attorney General William Wirt wrote an opinion addressing the question of the Senecas’ land title. He said that their right to the land, “however narrow,” was still “a title in fee simple” that the Senecas held as “a title of perpetual inheritance because it will be admitted on all hands that neither the present occupants nor their heirs so long as the nation subsists can be rightfully driven from their possessions.’ But that ‘fee simple’ title was qualified in some way, and Wirt saw it as “legal anomaly” because the Senecas, he believed, lacked the ‘right of alienation.” Wirt asserted that the Senecas had a right to lease as well as to sell their land, and he endorsed significant restrictions in the ways that Senecas might legally use their property. He wrote, “They have no more right to sell the standing timber, the natural production of the soil as an article of traffic than they have to sell the soil itself.” Wirt believed that the Senecas might use their land for “the purpose of subsistence,” but not a type of property they might exploit, use or develop for their community’s good. Cutting and selling timber would “waste” or destroy the value of their reserves; therefore, not only was logging without the Senecas’ permission illegal—it was “a trespass against their right”—but even timber harvesting by the Senecas themselves or their lessees was prohibited because it violated the rights of preemption title holders.

However, Wirt’s view was not accepted by all inside the government. Livingston, President John Quincy Adams’ appointee to investigate charges of bribery, corruption and coercion in the negotiation of the 1826 treaty, argued that “It cannot be that the Company can say to the Indians ‘when the right of preemption was granted[,] your Hunter condition was a Guarrantee to the purchasers that you should always remain wandering & never till the ground or cut the timber (which until recently was as valueless except to cover the game—as the game is now & could not have entered into the estimate at the time of the Purchase).’’ It is a fascinating statement. Livingston recognized Seneca social and economic transformation, and the importance of land in that process. The final article of the Canandaigua treaty provided an annuity to be paid in livestock, tools, and supplies to help the Indians make the transformation to an agrarian style of life similar to that of white American farmers. Statements from Washington, Henry Knox, and many others echoed this desire. Indians would stay on their lands, and in the eyes of the United States become “civilized.”

Livingston believed that the Senecas were doing just that. “The Company seeks to restrict the Indians to their aboriginal use of their acknowledged right of occupancy. I assumed the liberty of telling the Indians that they had the right of occupancy in perpetuity unrestricted as to the mode of occupying and that as they had left the Hunter state & adopted the agricultural they had the right to fell their trees to make room for the plough—that it would be advancing their interests to do so—that the trees cut with such intentions would be theirs.” Free use and enjoyment, right? This is all spelled out in Livingston’s report on the 1826 treaty.

What, then, did the Senecas think that they were giving up in 1826? The Senecas understood that by relenting to the Ogden Company’s demands they would reduce the size of their reservations and allow additional white settlement in western New York. Again, think of your piece of paper. You have some circles remaining on that piece of paper, each representing one of the Seneca reservations, with much of the rest shaded gray. I have tried to persuade you that in the Senecas’ view the reservations were for their exclusive use, lands that white people could not enter without their permission. The rest, we have established, was land to which they granted white people access, but on which they retained the right to hunt and fish. I have argued that this is something very close to ownership in the Senecas’ understanding of the land. You have circles on that piece of paper and areas shaded gray. As a result of the 1826 treaty, you can erase all but four of those circles, increasing the gray area. Those represent the Genesee Valley reservations sold in the unratified 1826 treaty. Of the four that remain, you can make each about a third smaller, reflecting the amount of land with which the Senecas ostensibly parted. The four reservations remain land for their exclusive use. The treaty said nothing about Seneca hunting and fishing rights, so they retained to the right to hunt and fish on the lands they supposedly had ceded.

Perhaps we are missing the larger point, the larger significance of what happened in 1826. The United States, after all, never ratified the treaty. There is no disputing this. The Secretary of War and the Commissioner of Indian Affairs both explained why they felt ratification was unnecessary, but their reasoning has frustrated historians ever since. Even the Committee appointed in the 1880s to investigate “the Indian Problem” in New York State concluded that the 1826 treaty “was never ratified by the Senate of the United States, or proclaimed by the President, and the Indians have for a long time past claimed that the treaty was invalid for this reason.”

The Senecas who did sign the agreement made clear that they were either deceived or coerced into signing. Those who agreed to the cession did so under duress. R. M. Livingston, who indicated that the combined population of Canawaugus, Squawky Hill, Big Tree and Gardeau was 448 in August 1826, collected depositions that make abundantly clear that the Senecas opposed sale of their lands until the company promised that it would ask them to sell no more of their lands if they assented to this sale. An exception was apparently made, according to white people affiliated with the Ogdens, for the President, who could initiate discussions of a sale. Jasper Parrish, in his deposition, stated that “among other things inducing them to sign the Treaty was an agreement by the Proprietors never to urge them to sell any more land.”

In Livingston’s 1828 report, for instance, there are the following statements from Senecas:

* William Jones, a “half blood (& interpreter to the missionary establishment), testified that “among other things inducing them to sign the Treaty was an agreement by the Proprietors never to urge them to sell any more land. Deponent thinks that the Donations aided in producing their assent to sell.” Jones was given $50 a year for life if he helped effect a sale. Jasper Parrish, who worked with the state, the federal government, and the Ogdens, said “that until the stipulation was signed by which the Indians believed themselves relieved from or secured against future importunities to sell, none of them signed the treaty.”

* Captain Strong, a Cattaraugus chief, said “We understood that we were either to sell or remove.”

* Chief Warrior, another Cattaraugus chief, said that Dr. Jimison “came and said he was sent up by Judge Forward, to inform the Chiefs that if they concluded not to sell, he would write on to the Sec’y of War, and there would be a road prepared for them to the Cherokee Nation. From that time they began to feel disposed to sell.”

* Black Snake said the same thing in his deposition. “Forward told them that they had either to sell, or that a path would be opened for them to the Cherokee Country. Greig told them that if they sold what was then wanted, the Company would never ask them to sell any more.” Black Snake assented to the sale “because they dreaded the thought of being removed.”

In the treaty itself, when it says that the Senecas retained the part of the reservations they did not cede “in as full or ample a manner as if these Presents had not been executed. Together with all and singular the rights, privileges, and appurtenances to the said, hereby granted premises, belonging or in any way appertaining and all the estate rights, title or interest, claim and demand whatever of them the said parties of the first part and of their Nation of in and to the said several tracts, pieces and parcels of land above describe except as above accepted.” The Senecas understood from the treaty that possession of their remaining lands would be undisturbed and unaffected by the sale. Livingston himself, in a letter to Secretary of War Peter Porter, indicated that the Senecas determination at the treaty not to sell their lands was viewed by the Ogden Company men as “an insuperable act of nonconformity to the will of government and the just claims of the Proprietors. The terrors of a removal enchained their minds in duress, and becoming petitioners in turn they submitted to the terms dictated—to sell a part to preserve the residue.” The Senecas, Livingston continued, “esteemed” this guarantee to pressure them no more to sell lands as “a Guarantee for the quiet enjoyments of the residue of their lands.”

Let’s jump ahead. We will move more than a century forward. We will move past the State of New York’s concerted efforts to allot Seneca lands and dismantle Seneca families by placing their children in boarding schools, like the Thomas School, which remained open into the latter half of the 1950s. We will move past many of the state’s efforts to skim the cream from whatever fragile prosperity that came to Seneca lands. Frustrated by the determination of the Senecas and other Haudenosaunee peoples to hang on to their lands, their culture, and their systems of governance, the state’s leaders successfully lobbied Congress to enact legislation to limit the power of New York’s Indigenous nations. The resulting legislation, known as the “Spite Bills” of 1948 and 1950, extended state criminal and civil jurisdiction over Indigenous lands in New York State. This occurred at the beginning of a period in American Indian policy known as the Termination Era. But even these laws, which did what Haudenosaunee people had feared for so long, recognized an important point: while extending its criminal jurisdiction over Indigenous nations, the law provided “that nothing contained in this Act shall be construed to deprive any Indian tribe, band, or community, or members thereof, hunting and fishing rights as guaranteed them by agreement, treaty or custom, nor require them to obtain state fish and game licenses for the exercise of such rights.”

A final point. A couple of years ago, Justice Neil Gorsuch, President Trump’s first appointment to the United States Supreme Court, ruled in a case called McGirt v Oklahoma that treaty rights can never lapse, expire, or disappear because of the mere passage of time. Over many years, the Supreme Court held that Congress possessed plenary authority over Indian affairs. Treaty rights exist, in other words, until Congress decides to exercise its plenary power to do something specific and unambiguous to make those treaty rights go away. I have in this essay tried to show you that these rights existed, that they extended beyond reservations, and that Congress has done nothing to abolish or repeal these rights. They still exist.

New York became the Empire State through a systematic program of Indigenous dispossession. In places, this process violated federal law. Dispossession was not a product of conquest. It was not inevitable. Nor was it the American Nation’s “Manifest Destiny.” In places it was quite simply a crime against the laws of the United States. Even when the United States acquired lands in a manner that was “legal,” the practices deployed by the land companies and their allies will repel people of conscience. They used deceit and coercion. Nobody who has looked at the historical record will deny this. We who own land in this state, as a result, are the beneficiaries of an unjust process of dispossession. We have run up an enormous debt. The question, for me, really is not a matter of whether or not this debt exists, but what am I, and what are you, going to do about it. You can pass laws proscribing the teaching of certain subjects. You can dismiss this as “woke” history, as some have done. But that’s chicken shit.

It’s not an answer. It’s not an argument. It’s an abdication, and an admission, in my mind, of complicity in a crime that too many people are too unwilling to talk about.