And the sins you forget, you may commit again.

Are there historical sins that can never be forgiven? Are their historical crimes so great that the guilt can never be washed away?

Last week a story appeared in the New York Times announcing that the “Holocaust is Fading from Memory.” Many adults, according to a recent survey, “lack basic knowledge of what happened—and this lack of knowledge is more pronounced among millennials, whom the survey defined as people ages 18 to 34.” 41% of Americans, as well as 66% of millennials, had never heard of Auschwitz. And, as Matthew Rozsa pointed out in Salon, it’s not just a Holocaust problem. Americans of all ages just do not know their history well at all.

I am not willing to fault the young people for that. Our education system, presided over by the overly-credentialed but unwise and unimaginative adherents of a testing regime, who celebrate STEM fields, who equate positive outcomes with “employability,” and who consistently challenge the relevance and even the necessity of training in the liberal arts and humanities, have done us all a huge disservice. We know little of where we have been, who we hurt, how we hurt them, who benefited, and how the processes of history have unfolded. We don’t know what we have done, how, and to whom. And it seems unlikely that without that knowledge we will ever be able to stop.

There are just a few weeks left in the semester. At the end of my Indian Law and Public Policy course in a few weeks we will discuss apologies for the historic treatment of America’s peoples. And in my course on the Early Republic, which I am teaching for the first time in twenty years, we have reached that point in the semester where I am discussing Antebellum slavery and the slave regime in the south. I like to ask students about apologies for slavery, too, given the horrible brutality of the entire system.

I have been at this a long time, and I can anticipate the answers. Apologies bring complications. Lawsuits, for instance. Or all the exceptions. My ancestors were not even here back then, and so on. As a nation, and as individuals, I encounter many people who do not like to second-guess, who are willing to say that the past is in the past and it is time to move on.

But if Americans do not know those histories—of dispossession and colonization in the first instance and enslavement and white supremacy in the second—and if they do not understand the chains binding the past to the present, the likelihood of them understanding what they might apologize for is remote at best. Why do something when you lack the knowledge to understand the problems that exist?

We like villains, for instance. We like to place blame. Doesn’t take much thought at all. Andrew Jackson was a real bastard, we might point out. But we might also suggest that he was hardly the only person to call for “Indian Removal.” And he was hardly the only person to benefit. Those of us who live on what was once native land should know that well. We do not, generally speaking, but we should. To many Americans the injustice that made them who they are remains invisible. I have met many people who sense that there is something off-putting and creepy about President Trump’s fixation with Andrew Jackson, but to ask them to explain why is another matter entirely.

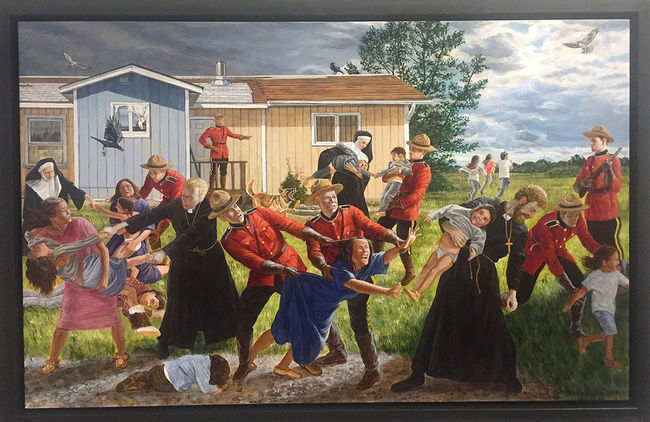

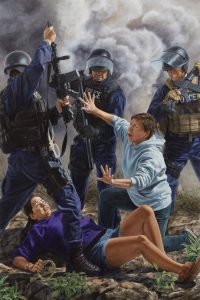

I have been listening to the “Finding Cleo” podcast produced by CBC Radio. It is a searing story of the legacies of Canada’s brutal decision to carry away 150,000 First Nations children into boarding schools, foster care institutions, and adoptions, in order to assimilate them. The podcast follows the victimized siblings of one small girl who also fell victim to Canada’s “Sixties Scoop.” Today is the product of many yesterdays, of many decisions, policies, and actions, the consequences of which whipsaw through time, spreading wreckage as they go. If your students watch the “The 13th,” they will recognize that slavery is hardly part of the past, that the injustices upon which the South’s “Peculiar Institution” rested are still very much with us. Incarceration Nation. Prison reform has received more attention than in the recent past, but the racial disparities in American prison populations quite simply is not a source of concern to many Americans. We watch our duly elected buffoon preside over the country, and bounce from crisis to crisis, while his trampy kids and corrupt appointees run a smash and grab ring. Important problems, the legacies of our nation’s sins, remain unaddressed, because too many people do not care, and too many people know too little to care.