I gave the following keynote address to the annual meeting of NYSACAC, the New York state organization for high school and college admissions counselors, which took place at SUNY-Geneseo earlier this month. In some ways, it encapsulates what I tell my students each semester on the first day of class in my Humanities class.

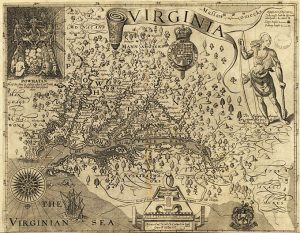

I am delighted to be here, and to join those who have welcomed you here to our beautiful campus. Geneseo, as a place, shows up in the historical documents long before Rochester existed, long before Monroe or Livingston counties, long before there was much of anything European established in what became the broader upstate region. It lays in the heart of the ancestral homeland of the Senecas, the keepers of the western door of the Haudenosaunee, the Iroquois Longhouse.

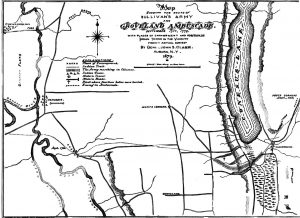

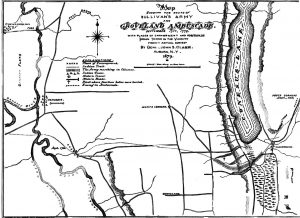

Seneca soldiers and diplomats who lived in this Genesee valley played a role in the history of two empires, the French and the English, in the Iroquois League and Conf ederacy, and in the history of the native confederations that threatened the existence of the British Empire in America and then the young United States in the 1790s. They continued to live in this valley, at least some of them, even after Major-General John Sullivan led Continental forces through the Finger Lakes in 1779, burning crops and villages, and scorching the earth, as he went. They were here in the 1790s and into the 1800s, before they moved to Allegany and Cattaraugus and Grand River in Canada.

ederacy, and in the history of the native confederations that threatened the existence of the British Empire in America and then the young United States in the 1790s. They continued to live in this valley, at least some of them, even after Major-General John Sullivan led Continental forces through the Finger Lakes in 1779, burning crops and villages, and scorching the earth, as he went. They were here in the 1790s and into the 1800s, before they moved to Allegany and Cattaraugus and Grand River in Canada.

Stories from the past. I could tell you more: about Mary Jemison, the white woman of the Genesee. She lived for a time as a captive, and adoptee, a refugee, and a Seneca homesteader down the road in what became Letchworth State Park, where you can see a statue of her and a replica cabin. There are some documents with her mark on them in the county courthouse at the end of Main Street, where she deeded Seneca lands she claimed to white men associated with the Ogden Land Company, among whom numbered one of Geneseo’s founding fathers. Her Seneca sons, who died violently, two of the three at the hands of their brothers, victims of the alcohol that could cut jagged holes in the fabric of Native American life. There are New York State historical markers all over this county. Biased, to be sure, but all telling historical stories about this part of New York State.

For nearly two decades, I have told stories like these to students at this school. I have taught a lot of students over the years, and told a lot of stories. I am a historian. That’s what we do. I am interested in the past, and its connections to the present. How things came to be. Continuity and Change measured across time and space in peoples, institutions and cultures. But all of that is just a way of saying that I am a guy that makes my living by asking questions. And I love the questions—the search for evidence, the complexity and the lack sometimes of definitive answers, and the stories—the stories are at the heart of all that we historians do as teachers and writers.

I imagine that in your line of work you have stories that you can tell, too, stories of young people who have all sorts of challenges in front of them, or who survive trauma and neglect, some who have succeeded wildly and some who have broken your hearts. I am sure you have stories of kids who are coming to you before they leave home to go to school, or to work, or into the service, or off to some experience—a gap year or a slack year or an adventure–and who want to begin writing their own stories for themselves, and perhaps by themselves, for the very first time. These are stories, too, of continuity and change, of how things came to be, of being and becoming. Some of these young people are becoming competent and capable. Or they may be developing generosity and compassion, and some of them might be frightened and uncertain, sometimes for reasons that go deep into theirs and their family’s past, layers upon layers of stories you may have to disentangle if you want to understand them, where they are coming from, and where they hope to go. Some of them do not know what their story is going to look like, or how to begin writing it.

Like you, I have seen students who fall into all of these categories, students who, whatever they are feeling, can do so much to make this world—our world—a better place.

I can also imagine, and only imagine, the time constraints that you, and our colleagues who are out there in the classroom, work  under in an era of increasing demands and declining resources. My teacher friends do so much, with so little, so often for people outside the building who have little understanding of what a good job actually looks like, who measure success in ways so foreign to the lived experience of you and your students. And so it is with some trepidation that I propose to you today, if we are truly “dedicated to serving students as they explore options and make choices about pursuing postsecondary education” as Article I, Section 1 of your association’s by-laws read, that there is more that we can and should do for these young people who are so important to all of our futures.

under in an era of increasing demands and declining resources. My teacher friends do so much, with so little, so often for people outside the building who have little understanding of what a good job actually looks like, who measure success in ways so foreign to the lived experience of you and your students. And so it is with some trepidation that I propose to you today, if we are truly “dedicated to serving students as they explore options and make choices about pursuing postsecondary education” as Article I, Section 1 of your association’s by-laws read, that there is more that we can and should do for these young people who are so important to all of our futures.

My oldest daughter is one of these young people, She is at this point in her life where she interacts with her counselor a bit in high school, and talks with an occasional admissions representative. She has entered this period that is so rich with opportunity and potential but also fraught with vulnerability. She is finishing up her junior year in high school. She has visited colleges and will visit some more and has begun to think when her way-too-busy schedule permits about what she might like to do with the rest of her life. She has received all sorts of advice on what sort of story she might write, and she has received a lot of advice on how to navigate the college admissions process. She has been plopped down in front of computers to navigate Naviance and see what her next step might look like. Programs to get her thinking about how to begin her story.

And based upon what I have seen as a parent and a professor, it seems to me that there is one area that is so essential to success in a college classroom, and especially at a liberal arts college like this one, that does not get talked about at high school enough: the importance of cultivating and encouraging intellectual fearlessness; to develop in young people the courage not to shy away from those things that seem to them–to all of us—to be extremely difficult. To master basic skills, of course. To be honest, curious, inquisitive, and relentless to be sure, but most of all, in terms of the questions they ask, the evidence they consider, the ideas they engage with, and the theses they advance, to be as fearless as they can be. Now, on campuses like this, in this country, in this global community, more than ever.

Geneseo, as I have said, is still a liberal arts college. It’s a phrase that gets thrown around a lot. We integrate the liberal arts into the curriculum whatever a student’s major. We here at Geneseo wear that label, a liberal arts college, proudly, and many of us still hope our students will, too.

But that is a difficult—an increasingly difficult—thing for them to do. I imagine that some of the students you advise have heard the jokes about liberal arts and humanities majors. They have worried parents who fear that their kids will not be able to take care of themselves without a “marketable” degree. Some of your students, before they arrive on campus, will already have been asked, “What are you going to do with that degree?” Sometimes those questions can come from innocent curiosity, like, really, what are you going to do with that degree. But these questions can also come with a barbed tip, too, in the sense that the liberal arts and humanities are thought by some people out there to have limited value because, unlike the STEM fields and business and “the Art of the Deal,” the liberal arts are too often thought of as adding little of value.

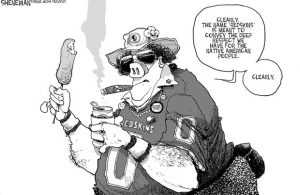

The governor of Florida, for instance, a few years ago, argued that we do not need more anthropologists. Another Floridian, a United States Senator, during his brief, quixotic run for the presidency said that we need “more plumbers and less philosophers.” The Lieutenant Governor of Kentucky told students at Eastern Kentucky University that they should not bother studying history, and that since they attended a public college, funded by taxpayers—people who work—that they should do something useful to the Commonwealth. Why should the state subsidize the study of French literature, the governor of that state asked. What value does it add for Kentuckians? Even in the SUNY system we have seen a diminishment in the perceived importance of the liberal arts, social sciences, and humanities.

And all of this is too bad, for I would argue that the study of these fields adds a lot, because they give us the cultural capital necessary to participate in a democratic society in a meaningful and constructive way. But thinking in terms of nuances, complexities, ambiguities, shades of grey; being one of the people who embraces the big questions, pursues the answers over the long haul, who appreciates the value of open debate and discussion, who endeavors to find truth, and digs like a terrier for answers—people like that can find these times we live in rough sledding. People who ask fundamental questions about why things are the way that they are and how they ought to be—they can be perceived as threatening to those in power, which is why we see this assault on institutions like the National Endowment for the Arts and the NEH, which fund in a variety of ways arts and humanities projects that explore issues that cut to the marrow of the human condition.

Our students now live in a world that you and I have helped to create for them where too many people confuse their feelings and their fears for facts, where being smart and engaged and critical and willing to ask questions can make one an object of scorn. They live in a world as well where complexity is so often dismissed, where big and difficult answers to the big questions are avoided, that asking these sorts of questions can take a certain amount of courage.

Let me give you an example. The former talk show host Bill O’Reilly used to have a segment on his shows where he sent a correspondent out to do “on the street” interviews where his goal was to expose the ignorance of the liberals he so often criticized on his show. One time the correspondent ran into a highly knowledgeable young guy, college-aged, who was more than willing to engage in a reasoned and informed debate and before he could get to his second sentence, Boom! “Nerd Alert!” flashed on the screen, as if being knowledgeable about public affairs and the world in which we live is a bad thing, something to make fun of.

Many Americans live in a world where they simply do not invest their time and energy to ask questions, stay informed. When we have a President who lies baldly to the press, and a press that is more concerned with ratings and clicks than in pursuing difficult stories, that is interested in fad and outrage and that has the attention span of a 2-year-old, we arrive at that dire point where the use of “alternative facts” can really be a thing that we can talk about with straight faces. We, collectively, the mature adults in the room, have modeled some very, very, poor behavior. We reason sloppily or lazily; we are dishonest, or cynical; we are cowards and grotesquely ill-informed. For instance:

- A sitting congressman told an audience that the theory of evolution and the Big Bang were “lies straight out of the pit of hell.”

- The chairman of a Senate environmental panel brought a snowball into that august chamber as proof that climate change is a hoax.

- When only 36% can find North Korea on a map, and that remaining majority is far more likely to favor military action against a nuclear power led by a deranged mad man;

- And when almost one in three Americans could not identify President Obama’s vice president, who was there for the entire eight years of his presidency,

- We have come pretty close to bottoming out.

Think about this: Americans, according to a recent survey, are more likely to be able to identify any two members of the Simpson family than any one of the five freedoms protected by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, rights that now, as they have been at many points in the past, are under assault. (I known, you think Homer, Marge, Bart, Lisa, and Maggie, but maybe not quite as readily of press, religion, speech, petition and assembly). 22% of Americans can name all five members of the Simpson family, while only one in one thousand could name all five first amendment freedoms.

We are complacent in the face of inequality and injustice. As the searing documentary “The 13th” pointed out, the United States has 5% of the world’s population, but 25% of the people who live their lives behind bars, and we are working hard to increase that percentage, if we are to believe the current United States Attorney General. But think about that: One out of every four persons who is incarcerated ON EARTH is imprisoned in the land of the free, and the home of the brave, though that freedom and that bravery is, at times, quite hard to find. People of color are imprisoned at rates far out of proportion to their share of the general population.

OXFAM reported in January of 2017 that 8 men, the wealthiest in the world, own as much as the poorest half of the world’s population. 8 men own as much wealth as the poorest 50%, 3.6 BILLION PEOPLE. The wealth of these eight men grew by half a trillion dollars over the course of the preceding five years, while the wealth of the poorest 50% fell by 1 trillion. At the height of his fame, Michael Jordan was paid more than all the factory workers in all of Nike’s factories combined.

We have seen gun-craziness, racism, rising antisemitism, fear. You know it is all there, and you can, I imagine, think of additional examples. Violence. White supremacists marching in New Orleans and Charlottesville to protect monuments explicitly commemorating white supremacy. The election of an incurious and juvenile president who has, at various times,

- insisted that freedom of the press—part of that pesky first amendment—does not allow the press to criticize him;

- that torture, specifically prohibited by American laws, should be brought back;

- that we should wall ourselves off from the rest of the world;

- claimed that women are objects who can be grabbed and groped at his pleasure; and that the norms and values and responsibilities of civil society and basic ethics simply do not apply to his family and favorites.

- I cannot keep up with it all—every time I thought I was done writing this address, another bit of news…And here is the point:

Rational, reasoned, and just public policy is difficult if not impossible without an informed, engaged, and rationally-thinking public willing to ask tough questions, to engage.

Fear. Many Americans live in fear: of immigrants and Islamist extremists–but a plastic surgeon botching your operation is more likely to kill you in the United States than a terrorist. Peanuts kill more Americans than terrorists, as John Oliver pointed out. Yet we are told to be fearful. And many of us do as we are told. People around the globe and in this country—some of them, anyways—seem to have more confidence in fear and anger and hate than in their opposites. With malice towards many, and charity for few; with little interest in heeding the call of the Old Testament prophets to care for the widows and comfort the fatherless, the weakest members of society, and to seek out injustice and correct oppression.

Our students are coming of age in this moment where a lot of really old issues—race and inequality and class and gender and violence and justice, are resurfacing in complicated and anguishing ways. The problems are out there. But to name them and to ask, “What can we do?” and to gather the information to solve them, that can be tough. And so many of these problems we face are rooted, in part, in a rejection of critical thought, in an embrace of the irrational, and a society with these problems can fall prey to demagogues with their simplistic answers, and will find it difficult to display emotional maturity, and will be prone to violence.

What are we going to do about all of this? I don’t know. But maybe if we are to make America great again, or as great as it might be, it might be the young people who you help send to a school like this one, who get a solid grounding in the liberal arts, whatever their majors, who will best see that “injustice anywhere” just may be a threat to justice everywhere. And that if it is “an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny, that binds us, one to another,” as Martin Luther King once wrote, that these kids, these young men and women, may be among those best suited to do something about it. So those of us at a school like this, we who think and reason; we, the people who read the footnotes–we can deploy that wisdom that not only makes our lives richer but makes the world a better place—–only if we have the courage to act, and to use it.

All of us, you and I, we need to do a better job with the young people we advise and teach.

After all, we live in and have helped to create a world where—when we stand up in the face of the problems before us and ask, “Why?” and when we insist on a reasoned and relevant response to that simple question—it’s like an act of subversion, and subversive acts, even the smallest ones, require a degree of courage, of fearlessness.

It can beat your down, if you let it. I see it occasionally on this campus. Despair. Hopelessness. Cynicism. Especially cynicism. I worry that it can beat down the young people with whom we work, if we do not do a better job in equipping them to be intellectually fearless. Again, look at the spectacle of public life that we are in the process of bequeathing to this generation. We might forgive them for an easy slide into a deep cynicism, but we must emphasize that cynicism is an intellectually lazy position, a colossal cop out or a reflection of a feeling of powerlessness.

But these young people do have power.

It can take courage to trust and to respect and to appreciate, as well as to care and to love, and to accept the validity of ideas presented by those with whom we would be predisposed to think we might disagree. To never underestimate others, to take people seriously, whoever that person happens to be, to accept the possibility that those with whom we disagree might have a point and, indeed, to admit that we might be wrong. To appear vulnerable in the face of those who despise us. It is not an easy thing for us, and it is not an easy thing for our students. It takes courage, and a willingness—a true commitment—to approaching everything and everyone with a readiness to see goodness and to be surprised.

It is so easy, and at a level perfectly understandable, to feel like the challenges we all face are too big and it is possible, I think, that we all feel at times like we are not enough to make a difference—that we need to be wealthier or have more expertise or access or a stronger prescription or whatever. But what if the students we worked with used their skills and their thoughts and their reason and acted as if they were exactly what was needed? If we all knew we could work to close the gap between the way things are and the way things ought to be, even a little bit, would we have the courage to act? Would we really do it?

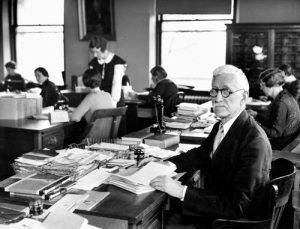

A long time ago I had a great history professor. His name was Albie Burke. He died about five years ago. And even though I left Cal State Long Beach where he taught in the late 1980s, I still got back to campus every other year or so to have lunch with him and to catch up, to talk about the Supreme Court, constitutionalism, politics, and all sorts of other things. We were both historians who sort of wanted to be lawyers. I can remember feeling nervous and unprepared before having to present some of my work in seminar, my thesis project on two really big Supreme Court cases in the field of American Indian law. And believe me, I was stressed out. We would meet in his very Spartan office, and he always made really incisive eye contact when you were speaking to him. Bright, bright, blue eyes. He would listen very quietly, never interrupting. Very comfortable with silences. And then when you finished, spilling out your guts, telling him how you were not ready, he would pause for a few beats and then say: “You will never be prepared. You still got to do it.” He’d smile just a little bit as he said that. It was a tough lesson for some of his students, I think, but his point was that you can spend all your time worrying and fretting and fearing and preparing and not doing. Fear can keep you from doing what needs to be done, in public life, and in terms of what you want for your own lives. His daughter told a similar story at his memorial service about many conversations she had had with him just like that. It is so easy to talk yourself out of pursuing your dreams, of tackling the challenges that may lie in front of you, and that lie in front of all of us.

It is this spirit that we must teach and nurture and cultivate.

How do we get there? Not by rubrics and grades and tests. Not by slapping labels on kids without making clear to them that at the end of the day they will have to decide whether that label will serve as an explanation for their failures or an obstacle, however burdensome and unfair, that they will have to overcome if they are to succeed.

I know that I have a lot to learn still. I learn a lot from my students. Maybe I do not know much at all. But I do know this: Students do not become better people, or more courageous citizens, through exams and grading. Students do not learn from many forms of assessment. The tests and the grades we assign do nothing to make them better people. And yet we do this still. The non-profit ETS brings in over 1.6 billion dollars a year.

And when grades or test scores are used to as great an extent as they are at present to determine opportunity—to open doors for some students and close doors for others—they can have the effect of reinforcing inequalities and systematic injustices that have stood for far too long.

The grades your colleagues give, and the grades I give, and the subjects that many of us teach, may in fact matter less for the scores and the content that we are mandated to cover than for what we give to our students to help them to learn to think, and reason, and ask tough questions. Students will remember how we made them feel, if we made them feel, more than any of the subject matter we teach them. I am willing to bet that if you take a minute, and think back to the time you spent in class, in high school or in college, and what you remember from those classes, that you might agree with me. I hope so.

Maybe we can be the types of teachers who worry less about grades and missed deadlines, who will believe their excuses, and give out more “A’s.” I am walking proof, after all, that there is little relationship between high school and even undergraduate achievement and later academic success. And nobody—NOBODY—will convince me that a sixteen or a seventeen or an eighteen-year old should have doors shut because they were not inspired or equipped by their overworked and underpaid teacher to complete their assignments, or able to place their rote work and assignments ahead of whatever crisis, great or small, was dominating their life. Grades and test scores, to too great an extent, measure the dutiful but not the beautiful parts of our students.

Students. I have used that word a number of times in this talk, but it is important to remember that we are talking here about young people—people like us years ago– with potential and with dreams who are still learning where their talents lie. And we need those dreamers. Stargazers. That’s what Plato called them.

Here’s what a student of mine wrote for her Humanities final just a month ago. Humanities is a course that we used to really value here, and that used to make Geneseo special and unique. I gave the students an essay by Roger Rosenblatt that appeared last fall in The Atlantic in which he reflected on his long career as a war correspondent, and the seemingly limitless capacity of people for inhumanity and barbarism. It is powerful, heartbreakingly beautiful essay. The assignment, in the end, asked students to write about human nature, justice, and the problem of evil, as the contemplated this article, and works by Sophocles, Plato, Thucydides, Augustine, More, the Bible, Shakespeare, and some others I am not remembering. “The question remains,” this very talented student wrote, “how do we account for all of the hatred, violence, and injustice that we witness? What words do we use to describe it? How can we possibly rationalize it and make sense of it? Where do we find its opposite in the world, and how do we eagerly point at that, so as to say, ‘See, this is also us. This is also me.’

“In a world and a human history overwhelmed by hatred, violence, and injustice, what counters it, I argue, is love, compassion, faith, and the courage to rise above it.”

Maybe we should refuse the rubric, and ignore the scores. Look for the beautiful. This rising generation of students is already better than us in important ways—their open-mindedness, their tolerance, their acceptance of difference. I really believe that. Encourage courage. We have a lot of influence. Or at least we have the potential to be highly influential: a cruel or an uncaring word from us, for example, even when cast off thoughtlessly or uncritically, or because we are stressed out or too busy, can do so much damage, while a kind word, a single note of encouragement, can do something that these students will remember for the rest of their lives, something that can help them write a beautiful life story.

So let’s do better. Let’s encourage fearlessness, even where we have failed to demonstrate it ourselves. I feel that I have the best job in the world. Really. There is nothing else that I can imagine doing because, like you, I get to spend my time talking to young people, many of whom are optimistic, who are neither jaded nor cynical but see the world as one with so much potential. And it is, for those with the courage to act. How cool is that?

And each and every day, I have the opportunity, if I choose to truly be present, to truly listen, to be awed by their achievements, humbled by the obstacles they have overcome to get to this college, inspired by their creative thinking, pushed by their challenging questions, and amazed by the alacrity with which so many of them seek out injustice, attempt to correct oppression, and in thousands of small ways show the vital courage to make the world—our world—a better place.

I have enjoyed this opportunity to speak to you. I thank you for listening, for giving me some of your time, and I hope that you enjoy and benefit from your time here at Geneseo, at this conference, and at this beautiful campus.

number of trucks on the road,” study author Ginger Gibson told National Observer. “There’s a whole whack of issues that don’t get considered until construction is happening and that’s too late.”