Progress for Pocahontas’s people seeking federal recognition. The United States House of Representatives last week approved by a voice vote the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act, H. R. 984. The Senate approved its version of the measure back in March. For background on who Thomasina Jordan was, you can read this resolution brought before the Virginia House in January 2000, a short time after her death.

According to the report in indianz.com, the measure would apply to the Chickahominy Tribe, the Chickahominy Indian Tribe – Eastern Division, the Upper Mattaponi, the Rappahannocks, the Monacans and the Nansemond Tribe. “All have agreed,” according to the report, “to a prohibition on gaming and all will be able to follow the land-into-trust process if the measure becomes law.”

This measure is important, and if you have read Native America, you will know well the challenges  these communities have faced in their efforts to obtain federal recognition: Warfare, dispossession, and enslavement, to be sure, but also the efforts of people like Walter Ashby Plecker to eliminate Virginia’s native peoples from the historical record, genocide by erasure. I write about Plecker in Native America, but your students might enjoy as well this piece from a couple of years back that appeared in Richmond’s Style Weekly. It’ll be certain to get a discussion going.

these communities have faced in their efforts to obtain federal recognition: Warfare, dispossession, and enslavement, to be sure, but also the efforts of people like Walter Ashby Plecker to eliminate Virginia’s native peoples from the historical record, genocide by erasure. I write about Plecker in Native America, but your students might enjoy as well this piece from a couple of years back that appeared in Richmond’s Style Weekly. It’ll be certain to get a discussion going.

Yet despite the bipartisan support for the measure, there are still obstacles. The president, of course, is a wild card, and he is mired enough in problems of his own making that it may take a herculean effort to bring the measure to this attention. And then there are members of the Senate who, in the past, have objected to Congressional recognition of American Indian tribes. The process, they assert, should follow the protocol laid out in the 1978 Federal Acknowledgment statute. Three times the House has approved this measure. But because one of those senators, Tom Coburn of Oklahoma, has retired, Virginia Senator Tim Kaine is optimistic that this time the outcome might be different. “We are correcting a historical injustice that we’ve endured since,” said Chickahominy chief Stephen Adkins, “you know Jamestown in 1607, and we just have not been accorded the dignity that we should be accorded as native people.”

I like to assign my students the text of the 1978 statute. I use the edited version in Prucha’s Documents of United States Indian Policy, a reference work I generally assign in the survey course. The Office of Federal Acknowledgment, which oversees the BIA process spelled out in the statute, has a website that is not easy to use, but might reveal to students something of the complexity of the federal bureaucracy and the sort of work required to submit an acknowledgment petition. The standards the 1978 statute sets for federal recognition for native peoples are extraordinarily difficult for many native communities to meet. The process is expensive and time-consuming. The problems the current BIA process creates have been addressed extraordinarily well in the volume edited by Amy E. Den Ouden and Jean M. O’Brien entitled Recognition, Sovereignty Struggles, and Indigenous Rights in the United States, published by the University of North Carolina Press in 2013. There are some other works listed in the Manual for Instructors and Students if you want to read more deeply.

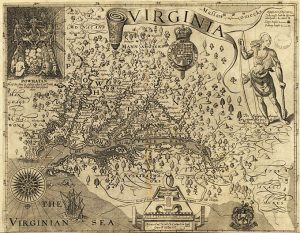

Because Congress has plenary authority over Indian affairs, it can grant recognition apart from the clunky BIA process. It has not done so since the middle of the 1990s. That is a shame. The BIA process needs repair. That is a truth acknowledged by everyone with a stake in the process. Let’s hope that this time, the Senate and the President support the recognition of these native peoples who greeted the soldiers and settlers who planted the first permanent English settlement in North America.