Yesterday was the anniversary of the Pulse nightclub massacre that took place a year ago in Orlando, the largest mass shooting in recent US History. It was also the fiftieth anniversary of the Supreme Court’s decision in Loving v. Virginia, the case which struck down laws that prohibited marriage across the color line.

You may have seen the beautifully quiet and restrained telling of this story in last year’s Oscar-nominated film that starred Ruth Negga as Mildred Loving and Joel Edgerton as her devoted husband Richard. The film avoided grandiose speeches, courtroom melodrama, and focused instead on the struggle of a couple, white and black, to hold things together in the Jim Crow south.

There was more to the story, however, for Mildred Loving always claimed that she was Native American, a descendant of Virginia’s native peoples. This story is told in Sally Jacobs’ piece that appeared on WGBH. You might find Jacobs’ story useful in your classes.

[UPDATE: And you might find it useful for more than just the story. Arica Coleman, mentioned below, wrote a fantastic book on this subject, and she has accused Jacobs of plagiarizing her work. You should read Coleman’s criticism here and in the comments section which follows Jacobs’ piece. Professor Coleman presents a powerful case, and we need to hear Jacobs’ response. MLO]

Mark Loving, Mildred’s grandson, contacted the Virginia Department of Historical Resources because he objected to the description of his grandmother on a state historical marker as “a woman of African-American and Virginia Indian descent.” So said Jacobs in her piece for WGBH. Mark Loving objected to the suggestion that Mildred Loving was anything other than a Native American woman. “I know during those time that there were only two colors,” he said in an interview from last November, “but she was Native American. Both her parents were Native American. Mildred herself insisted in 2004 that she had no black relatives, according to Arica Coleman, who interviewed her for the fantastic book she wrote on mixed-race marriage.

Race is never simple, and Virginia’s history is a messy one. In 1924, for instance, the Virginia legislature passed its “Racial Integrity Act” which defined white people as having “no trace whatever of any blood other than Caucasian.” The act included the so-called “Pocahontas exception,” stating that “persons who have one-sixteenth or less of the blood of the American Indian and have no other non-Caucasic blood shall be deemed white persons.” Many Virginians, blissfully unaware that some of Pocahontas’s descendants had sired children with slaves, attempted to tie themselves firmly to Virginia’s romantic past by claiming descent from Pocahontas. Their interests had to be protected. Anyone who was not white, under the provisions of the law, was “colored.”

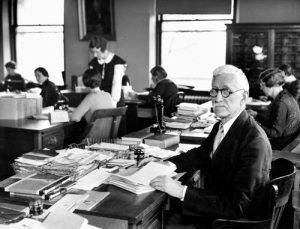

I take some time with laws like these in my classes in order to explain to them how nonsensical and ridiculous all of this is at a fundamental level. Race is a construction, an invented category. The blood that flowed through one’s veins did nothing to effect culture and belief and values and behavior. Still, Virginians enforced the Racial Integrity Act with a vengeance, and the Commonwealth’s first registrar of the Bureau of Vital Statistics, Walter Ashby Plecker, was a true believer. “Let us turn a deaf ear,” he wrote revealingly in 1925, “to those who would interpret Christian brotherhood as racial equality.” Virginia Indians, he believed, were not real Indians: they had been mongrelized, mixed with peoples of African descent, and as such he ordered his employees to alter the birth certificates of Indian children.  This was erasure, an attempt at extermination carried out with pens and paper. The certificates now would read “colored.” Plecker claimed that he had science on his side—the same “eugenics” that later fueled the Nazi holocaust—but he admitted to close friends that he routinely changed racial designations from Indian to colored without any evidence.

This was erasure, an attempt at extermination carried out with pens and paper. The certificates now would read “colored.” Plecker claimed that he had science on his side—the same “eugenics” that later fueled the Nazi holocaust—but he admitted to close friends that he routinely changed racial designations from Indian to colored without any evidence.

Plecker’s racist crusade made it difficult for many native peoples in Virginia to prove that they were Indians. The vital records upon which such a designation relied, after all, had been altered. Native peoples in Virginia asserted a third racial identity in a biracial society. They did not attend black schools because they felt no necessity to accept Plecker’s logic. Many wanted access to the better facilities available to white Virginians. Some of those who could pass as white did so, but many of Wahunsonacock’s descendants struggled in the face of this racist legal code.

During the Second World War, Commissioner of Indian Affairs John Collier complained about Plecker’s strict enforcement of Virginia’s racist legal code but Plecker was convinced that thousands of “mulattoes” in Virginia “are striving to pass over into the white race by the Indian route.” Plecker determined to keep the races pure, and the lines between them distinct. When a draft board in Richmond ordered three Rappahannock men to report to an induction station for African American soldiers in Maryland, they refused. Authorities in Virginia prosecuted the men and sentenced them to six months in prison. The government allowed Chickahominy soldiers to serve in white units only after the tribe demonstrated its own racism toward African Americans: Chickahominies who married black people faced expulsion from the community; they tried to keep African American farmers away from the reservation, and prohibited black doctors and preachers from visiting their communities. Most of the Virginia Indians who served did so in white units, but not without an enormous struggle.

There were solid historical reasons for Mildred Loving’s family to claim to be Indians. But people on the margins intermarried throughout the South. They always did, and racial identity could be fluid on the marchlands of the empires and the colonial state.

They always did, and racial identity could be fluid on the marchlands of the empires and the colonial state.

As Jacobs shows, in Virginia, along Passing Road, where the Lovings lived and loved, there is today debate about Mildred Loving’s identity. Who she is still is debated. In an attempt to navigate these troubled waters, Jacobs reported, “the state of Virginia rewrote its highway marker to describe the Lovings simply as an interracial couple and removed all mention of her being either African-American or Native-American. But that didn’t quell the controversy.”

In the face of local opposition, the state last week moved the location of the highway marker away from a roadside several miles from the Lovings’ gravesite. It’s now to be near the former Virginia Court of Appeals in Richmond, where the Loving case was once heard, over an hour’s drive away. Despite the controversy, Virginia Governor Terry McAuliffe is set on Monday to dedicate the marker, which has been in storage for over a year.

That some of your students likely will have some familiarity with the recent film version of the Lovings’ story, and the recent salutary discussion across the country of how love must trump hatred, bigotry and racism, it might be useful to discuss this important case in Native American history classes. And if not the Lovings’ story, there are similar cases throughout the American South, and throughout Native America.

If Mildred Loving didn’t have any black relatives then who was the cousin she went to go live with in the ghetto of Washington DC? Who was the father of her first child…give me a break.

I think that terms are being used to confuse people. She didn’t identify as having “African” blood which could have been true, “natives” are copper colored people or better yet aboriginal Americans are copper colored. What color was she? She certainly may be full native and “black” but not be “African American”.

They should take her out of the African American history museum. That’s would have offended her.