I did not pay much attention to Jimmy Carter during his presidency (I was too young at the time to care much), but I have believed for many years that he is among the greatest of the American nation’s former presidents.

Ask people of a certain age what they felt about the Carter presidency you will often hear harshly critical reviews. He was weak and indecisive, unable to solve a national “malaise,” serious economic crisis, and the Iran hostage crisis. Historians are gradually coming to view him in less unforgiving terms. According to Siena College, Carter ranks 24th in their list of American presidents. He was ranked second only to Lincoln for presidential integrity. Most polls place him right in the middle: well ahead of all those gilded age and antebellum failures, and ahead of Nixon, the second Bush, and Trump as well.

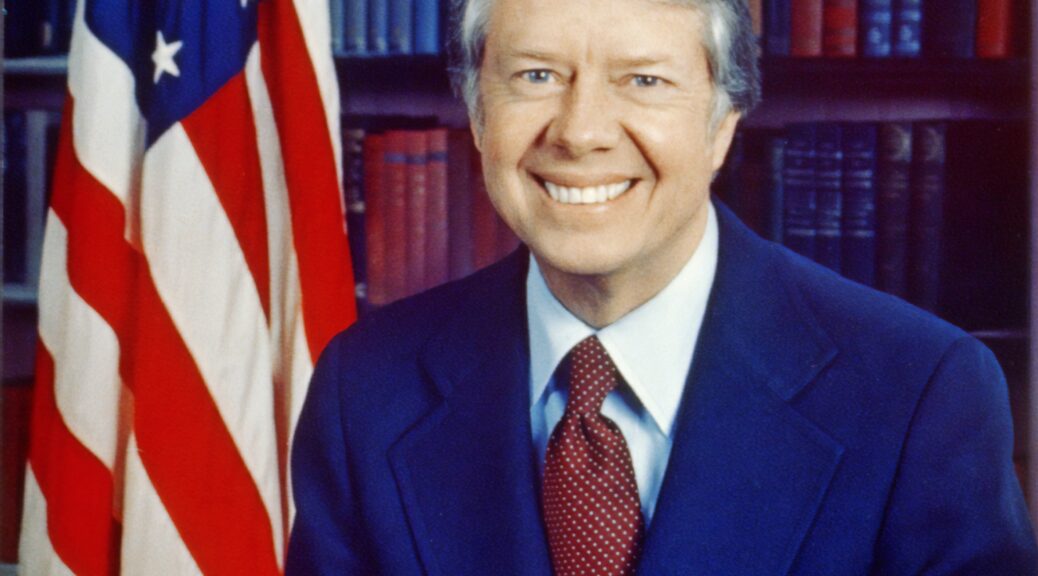

In the coming days we will see many assessments of Carter’s presidency. I expect none of those to say anything about Indian affairs. His policies with regard to Indigenous peoples in Alaska brought lasting change and significant hard feelings. (A good review is available here.) He famously posed for a White House photo with “Pretendian” Iron Eyes Cody. But President Carter also signed some of the most significant legislation enacted in any presidency.

President Carter followed and expanded on the shift towards “self-determination” in the conduct of the American Nation’s Indian policy. Congress took the lead, continuing work it had begun under Nixon and Ford, but Carter can take credit for signing the legislation into law.

Acknowledging that in the past the United States had pursued policies that “resulted in the abridgment of religious freedom for traditional American Indians,” Congress in August approved the American Indian Religious Freedom Act, which pledged the United States “to protect and preserve for American Indians their inherent freedom to believe, express, and exercise the traditional religions of the American Indian, Eskimo, Aleut, and Native Hawaiians, including but not limited to the access to sites, use and possession of sacred objects, and the freedom to worship through ceremonies and traditional rites.” AIRFA was limited in its effect by the Supreme Court, but it was an important statement from a government that historically had done so much to eradicate Indigenous religions.

Aware of the growing number of native peoples who belonged to communities that had neither signed treaties with the United States nor been the specific objects of federal legislation, Congress in early October established a set of guidelines for the “Federal Acknowledgment of Indian Tribes” that had not been officially recognized by the government in the past as Indian. The “acknowledgment” statute required that an Indian tribe, in order to be formally recognized as such by the Interior Department, demonstrate that they had “been identified from historical times until the present on a substantially continuous basis as ‘American Indian,’ or ‘aboriginal.’” They needed to demonstrate as well that the members of the community had inhabited a specific area or that they live “in a community viewed as American Indian and distinct from other populations in the area.” The petitioning tribe was also asked to establish that it had “maintained political influence or other authority over its members as an autonomous entity throughout history until the present.” Acknowledgment, the statute read, “is a prerequisite to the protection, services, benefits, from the Federal Government available to Indian tribes.” Such acknowledgment, the statute continued, “shall also mean that the tribe is entitled to all the immunities and privileges available to other federally acknowledged Indian tribes by virtue of their status as Indian tribes as well as the responsibilities and obligations of such tribes.”

Two weeks later, Congress passed the Tribally Controlled Community College Assistance Act, which provided grants for the operation of junior colleges on Indian reservations in order “to insure continued and expanded educational opportunities for Indian students.” Native communities had long recognized the importance of higher education, but access had always been a challenge. Cankdeska Cikana Community College, formerly known as Little Hoop College, was founded by the Spirit Lake Dakotas in North Dakota in the early 1970s. The college provided vocational and technical training, but also a curriculum that fostered “the teaching and learning of Dakota culture and language toward the preservation of the tribe.” Other communities established colleges throughout the West early in the 1970s, beginning with Navajo Community College. In response to the passage of the 1978 statute, a number of western tribes established new institutions of higher learning emphasizing a culturally relevant curriculum. Little Big Horn College, founded at Crow Agency on the Crow Reservation, struggled to survive with scarce resources in its early years but grew into a successful junior college. From thirty‐two students during its first semester in 1981, now more than 300 students enroll each term. All take courses in Crow Studies alongside a variety of skills‐based programs and courses designed to prepare them for transfer to four‐year colleges.

Congress in 1978 attempted to address the legacies of some of the nation’s most destructive policies toward Indigenous peoples. Early in November, Congress enacted a series of educational reforms for schools operated by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, designed to provide equal educational opportunity for Indigenous children. One week later, Congress passed the Indian Child Welfare Act, designed to halt the traumatic removal of Indigenous children from their homes through fostering and adoption. The problem was severe. Dakota Sioux at Spirit Lake, for example, had asked the Association of American Indian Affairs (AAIA) to investigate such removals, and the AAIA reported that of the 1100 Dakotas under the age of 21 who lived at Spirit Lake in 1968, 275 had been separated from their families. In states with large Native American populations, the AAIA found that between 25% and 35% of children had been removed from their homes. Indigenous peoples organized to halt this highly destructive practice, and the battle for the passage of the Indian Child Welfare Act, according to its best historian, “represented one of the most fierce and successful battles for Indian self‐determination of the 1970s.” ICWA, as it’s known, committed the United States “to protect the best interests of Indian children and to promote the stability and security of Indian tribes and families by the establishment of minimum standards for the removal of Indian children from their families and the placement of such children in foster or adoptive homes which will reflect the unique values of Indian culture.”

Decisions by the Supreme Court have already weakened many of these signal legislative achievements, and decisions looming on the Court’s calendar threaten to do even more damage. Carter certainly accomplished less than he might have hoped, but by following the lead of an energized legislative branch, he brought far-reaching change. In the assessments of his long career that appear in the coming days, this should not be forgotten.