And it is worth worrying about.

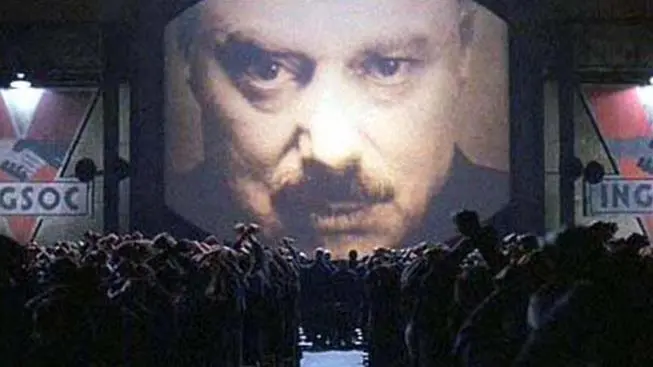

It is known as Florida House Bill 999. Those numbers are what you dial when you experience an emergency in Great Britain. In that sense, the numbering is fitting, for this bill poses a grave threat to intelligence, critical reasoning, and freedom of thought. It is no laughing matter.

The bill applies to all public postsecondary institutions in the Sunshine State. It empowers a Board of Governors to “align the missions of each constituent university with the academic success of its students; the education for citizenship of the constitutional republic; and the state’s existing and emerging workforce needs,” among other things. The Board must “provide direction to each constituent university on removing from its programs any major or minor in Critical Race Theory, Gender Studies, or Intersectionality, or any derivative major or minor.” They will also oversee an “Accountability Plan” that lists majors by the salary of their first-year graduates, and demands the collection of evidence on the universities’ promotion of “education for citizenship of the constitutional republic and the cultivation of the intellectual autonomy of its undergraduate students.”

Faculty members who choose not to toe the line can face discipline. The Board of Governors has the power to “initiate a post-tenure review of a faculty member at any time with cause.” Each state university board of trustees can make decisions for hiring and is not “required to consider recommendations or opinions of faculty of the university or other individuals or groups.” In other words, academic departments would not have a role in assessing the expertise of their would-be colleagues. Faculty cannot be trusted with hiring new faculty. Hiring decisions may not use “diversity, equity, and inclusion statements, Critical Race Theory rhetoric, or other forms of political identity filters as part of the hiring process, including as part of applications for employment, promotion and tenure, conditions of employment, or reviewing qualifications for employment.” Each school’s Board of Trustees may also “review any faculty member’s tenure status,” should they fail to conform. Shut up and take it, the state legislature is telling faculty, and if you do not like it we will ruin your life.

This is dangerous and draconian. It flies in the face of everything an education is supposed to be. Free-inquiry is not a cardinal value on Florida, where legislators with little expertise in education are crafting policies for universities.

The legislation also proposes to create the Florida Institute for Governance and Civics, which will “provide students with access to an interdisciplinary hub that will develop academically rigorous scholarship and coursework on the origins of the American system of government, its foundational documents, its subsequent political traditions and evolutions, and its impact on comparative political system.”

That may sound relatively benign, but its not. The Institute will “encourage civic literacy in the state through the development of educational tools and resources for K-12 and post-secondary students that foster an understanding of how individual rights, constitutionalism, separation of powers, and federalism function within the American system of government.” This includes holding on-campus forums to allow students to hear from “exceptional individuals who have excelled in a wide range of sectors of American life to highlight the possibilities created by individual achievement and entrepreneurial vision.” This is all coded language. Horatio Alger would be proud. There is no systemic injustice in America, and students in Florida should learn that the only reason for their failure can be their inability to work hard and think big.”

Historians clearly are part of a problem that the Florida State Legislature hopes to eliminate. “General education core courses,” the legislation reads, “may not suppress or distort significant historical events or include a curriculum that teaches identity politics, such as Critical Race Theory, or defines American history as contrary to the creation of a new nation based on universal principles stated in the Declaration of Independence.” History and other courses “with a curriculum based on unproven, theoretical, or exploratory content” might be accepted as electives, but not for general education. Students should stick to “this nation’s historical documents, including the United States Constitution, the Bill of Rights and subsequent amendments thereto, and the Federalist Papers.”

The language in the legislation is vague and unclear. Critically important terms are left undefined and could conceivably lead faculty members teaching theoretical physics on the hot seat. What, to the legislators, is the meaning of “intersectionality”? Of “Critical Race Theory”? What, for that matter, do they mean by “a curriculum”? The legislature, I suspect, want the small number of people who read this bill not to worry about its contents: a proposal to shut off entire fields of inquiry aimed at understanding and proposing solutions to demonstrable and easily-documented injustices in American life. But that a bill of this sort could even be considered is a sad state of affairs for a Nation ostensibly founded on Freedom.

Action is required. While the leader of the American Historical Association bitches and whines about “presentist” scholarship, Florida lawmakers are setting fire to the very idea that students should be exposed to ideas that challenge them, make them feel uncomfortable, or aware of the obvious and yawning gap between the way things are and the way things ought to be. This country is not healthy, and the problems we face today have historical roots. Meanwhile, the entire historical profession has fallen victim to a process of slow strangulation as public university systems deal with declining state funding. Much of the extraordinary talent of a generation of historians has been squandered. Public historical illiteracy is growing by leaps and bounds.

And now, this spate of Republican bills crushing free inquiry and silencing dissent. This legislation is racist and dangerous, a threat to all who value freedom and the ability to raise troubling questions. It is incumbent upon all of us who care about the field of history to explain why. Each of us who believes in the importance of Intellectual Fearlessness, and the importance of raising big questions, more than ever, must act. Each and every chance we get.