I have been thinking a lot about a quote from Angela Russell, a citizen of the Crow Nation in Montana who participated in the African American Civil Rights Struggle, but who was also inspired by Native American protests like the “Fish-In” movement in the Pacific Northwest, where Indigenous peoples courted prosecution under state fish and game laws to demonstrate their commitment to their federal treaty rights. Reflecting on what she saw around her in the 1960s and 1970s, she wrote “that it was the Indians who probably originated demonstrations and public protesting.” She could think of “countless examples in Indian history of demonstrations and protest.”

I like this quote a lot, as simple as it is, because it forces us to think about what we mean when we talk about Native American activism, in terms of content, chronology, and context. If you take a second, and think about the images that come to mind when you read the word “activist” or “activism,” I am willing to bet that the images that come to mind do not embrace the breadth and depth of the Native American experience.

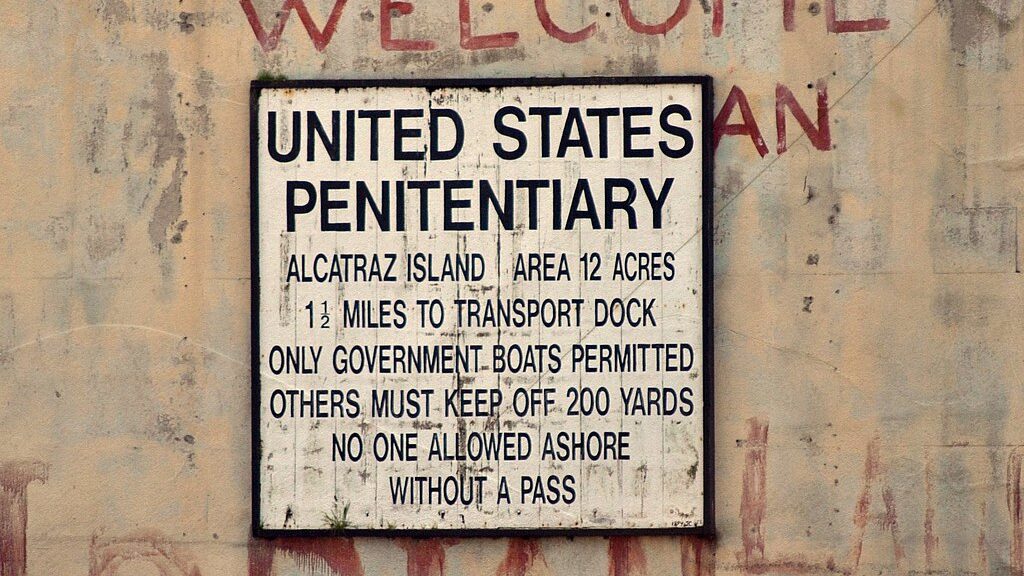

So, activism. What does it mean? And what does it mean in the specific context of Native America? As members of political communities the existence of which long predated the United States, they quite often have organized, and protested and fought to protect and defend their nationhood, their sovereignty, and their very identities as members of native nations. At times this has taken forms that will likely be familiar to all of you, images similar to what came to mind when I asked you to think about the meaning of the word “activism”: protest and demonstration designed to either bring attention to an issue or to provoke a tension, in Martin Luther King’s words, that makes clear the fundamental injustice of the current state of affairs in a given time and place. We saw examples of this nearly a century ago when Haudenosaunee peoples joined in something called the Indian Defense League of America to cross the Lewiston Bridge over the Niagara River between New York and Canada to demonstrate their treaty right to cross and re-cross the international boundary without interference or impediment from settler states. You have seen it in the occupation of Alcatraz Island in 1960 and 1970, the standoff at Wounded Knee in 1973, and, more recently, at Standing Rock in 2016 and now at Oak Flat in Arizona. These all share in that they were big, dramatic, attention getting events.

Daniel Cobb, a fine historian who has written extensively about this subject, defined activism as “politically purposeful acts.” That is a broad definition, perhaps too broad, but useful nonetheless for understanding the long history of Indigenous peoples’ assertions of their continued right to exist in a society that sees them as little more than a part of the past, or as a source of raw materials, or a stockpile of romantic images about the past cashed in or exploited to serve the needs of white people, or the occupiers of lands laden with mineral wealth and fossil fuels who need to get off and go away so that we can feed our societal addiction to petroleum.

Activism in Native American communities, in an American society that challenges their very right to exist, questions their nationhood, and in the not so very distant past invaded their homelands, dispossessed them, removed from them their children, infected them with diseases, and destroyed the basis of indigenous economies, can take many forms as they challenge those forces that have done so much damage and try to undo the lingering demands that colonization makes through the exercise of sovereignty and self-determination.

I write about the Onondagas. Over the centuries they have weathered invasions of their homeland, infectious imported diseases, attempts to dispossess them, and eradicate their entire culture and, yet, they still are there. In the face of state and federal policies they have consistently asserted a powerful autonomy and live lives of independence. It is an incredible story. If any number of people had had their way, the Onondagas would no longer exist. They would be gone. But there they are. Challenging the settler state; asserting autonomy and functional independence—this activism is significant and challenges the status quo. Assertions that we are still here, despite all the US and the state has done, are significant acts. There are others.

The Red Power movement—Alcatraz, the BIA takeover, and Wounded Knee—along with a notion that Native peoples are victims and helpless and tragic– has received so much attention that it has obscured the other varied efforts of native peoples to act on the principles of self‐determination, sovereignty and nationhood, to promote the interests of their communities. Women in Native American communities in the 1960s, for example, organized and marshaled evidence to counter something called the Indian Adoption Project, which resulted in part in between 25 and 35% of Native American children being removed from their families, either into the foster care system or adoption. This movement by Native American women was arguably the most successful activism of the era, pushing Congress to enact the Indian Child Welfare Act, a measure of great significance in the preservation of Native American families, even if it remains under siege by conservative evangelicals who continue to see Native American families as degraded, debauched, and unfit.

All sorts of activism. And then there is the quiet work of asserting sovereignty and defending nationhood. These, too, are politically purposeful acts. The Cherokees, for instance, used the award money it received from the Indian Claims Commission to assert itself as a regional economic power. The Cherokee Nation in 1967 built a hotel and restaurant on its land, and employed its own people in the construction and management. A tribal complex followed, which included an arts and craft center and tribal government offices. In 1969, the Cherokee Nation founded Cherokee Nation Industries to provide jobs in manufacturing for Cherokee Nation citizens. Landless and urban Indians in Washington, in a powerful 1973 report that charged the state government with carrying out a campaign of “ethnic genocide by assimilation,” and supporting the process of “destroying our identity,” announced that they would hold on to “the scraps and parcels” of their culture that remained and to work “as earnestly as any small nation or ethnic group was ever determined to survive and retain its identity.” They were critical of better-known activist groups like AIM, whose protests indeed garnered for them much attention. Unlike AIM, they did not see protest as the way to better their nations. They spoke of institution‐building. Because the Puyallup Reservation was so close to Tacoma, the tribal government had created a number of programs for the urban Indian population: the Indian Education Center, established in 1971, with representation coming from the Puyallup, Nisqually, and Muckleshoot communities; the Tacoma Area Native American Center (TANAC) incorporated in 1972 “with the express purpose of providing community organization for Indians and Alaskan Natives which in turn would promote unity and cooperation among all Indian people”; and groups for Native American students at Tacoma Community College. There were a host of organizations in Seattle: service organizations like the Chief Seattle Club, the Seattle Indian Center, and the United Indians of All Tribes Foundation; education and employment programs, advocacy groups, legal aid, health, and recreation. This is sovereignty in action. And it has occurred all over North America.

Native peoples have used that sovereignty to create and reinvigorate communities, revitalize language and culture, provide for the well‐being of their people, engage in sustainable economic development, and lay plans for a future in which they will play an important role in American society. The United States, and state and local governments, today routinely express their willingness to support self‐determination. This in itself is a significant break from a not‐so‐distant past when federal officials anticipated the disappearance of tribal governments and the assimilation of native peoples into the American mainstream. At times, non‐Indian Americans speak of justice, of building long‐term relationships with their native neighbors. But the recent past has shown as well that despite the significant accomplishments of native peoples in governing their communities and promoting their people’s interests, the promising signs of cooperation, and the increasing presence and acceptance of native peoples on the national stage, that in general non‐Indian Americans will support freedom and autonomy for native peoples only to the point where the exercise of these rights begins to threaten their own interests. Native peoples can meet this challenge. They have little choice. For nearly half a millennia, Europeans expressed their expectations that native peoples would disappear. For much of the nineteenth century, American policy‐makers anticipated Indian extinction. And even within the last half‐century, American officials looked towards the “termination” of American tribes. No longer. Sovereign tribes are stronger today in terms of their culture, their economic strength, their governing capacity than they have been for a long time. They are more active in defining and shaping their identities—with all the ambiguities and complexities that accompany that endeavor—than at any time in the past. I close, then, with a statement that would have been difficult to express at earlier periods when missionaries spoke of converting and transforming Indians, or when soldiers plotted to burn their fields, or reformers carried off their children to boarding schools, or settlers and bureaucrats swiped their lands: native peoples have a future that Native peoples have shaped for themselves, through their own actions, and their own activism.