Outgoing Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell has completed her exit memo, touting the accomplishments of her department during the Obama years. Jewell does not cover everything, but the memo does reveal that government can do important work in Indian affairs, and that it can be a force for good in Indian Country. I cannot say for sure how many of the men and women staffing the new Trump administration will share that view. In any event, you can read Secretary Jewell’s memo here. Jewell clearly is most proud of the land buyback program funded as part of the Cobell settlement. If you have students–or are a student–casting about for a term paper topic, an assessment of the program could be a valuable project. Check out the 2016 Status report for the Land Buy Back program here. The Interior Department website will provide you with additional information. And although President-elect Trump has said nothing about Native American affairs since his election, journalist Mark Trahant does a nice job of setting out a policy agenda upon which–one hopes–rational public servants might agree.

Category Archives: Uncategorized

#NoDAPL

Last night I appeared on WXXI-TV’s show “Need to Know” to share my thoughts about the Dakota Access Pipeline and what the future looks like in the face of an impending Trump presidency.

Why Can’t I Dress As Pocahontas for Halloween? And Other Thoughts

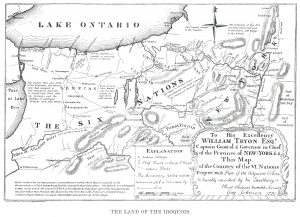

I like to show this map to my students. It is the Tryon map of the Six Nations, drawn five years before the colonis ts imperial officials hoped to control declared their independence. I ask my students, when they look at it, to forget all that they know about the subsequent history of the Empire State. Look at this map, drawn at one point in time. “Read it like a text. What do you see?”

ts imperial officials hoped to control declared their independence. I ask my students, when they look at it, to forget all that they know about the subsequent history of the Empire State. Look at this map, drawn at one point in time. “Read it like a text. What do you see?”

It’s such an obvious question that there is usually a brief silence. So I ask them to look at the map and tell me, “what, on this map, is New York? Where on this map is New York?” We talk, and quickly it becomes apparent. You cannot miss it. New York, as a geographic entity, did not exist much past Schenectady, and much beyond the Hudson River Valley. Much of what we call the New York today was, in 1771, “The Land of the Six Nations,” Iroquoia.

It is helpful to keep this in mind, because a large part of the imperial project, the core of what many scholars now call settler colonialism, was the erasure of native peoples from the American landscape, either through assimilation or annihilation. The settlers will expand, and the Indians disappear, their disappearance itself legitimizing the settlers’ claim to the land. Indians are always part of the past, always in the process of disappearing, of being swept into the dustbin of history.  They are erased, the settler state’s claims to sovereignty legitimatized, and the concerns of native peoples today more easily dismissed.

They are erased, the settler state’s claims to sovereignty legitimatized, and the concerns of native peoples today more easily dismissed.

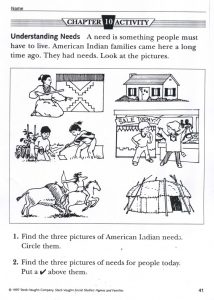

If you are a student, try this exercise. Ask some of your classmates to define an Indian or Native American. Have them tell you what comes to mind when you mention the word “Indian” or the phrase “Native American.” Play with them a word association game. In New York State, where I live, occasionally a student will mention gaming or smoke shops, but by and large the images they will conjure will be drawn from the past. It is something that many of us are taught from a very young age. Find “three pictures of American Indian needs” in the assignment here. The dutiful child will highlight the wigwam, the bison, the blanket weaver. Now “find the three pictures of needs for people today.” Erasure. Indians as part of the past.

smoke shops, but by and large the images they will conjure will be drawn from the past. It is something that many of us are taught from a very young age. Find “three pictures of American Indian needs” in the assignment here. The dutiful child will highlight the wigwam, the bison, the blanket weaver. Now “find the three pictures of needs for people today.” Erasure. Indians as part of the past.

So when you dress up in an “Indian Costume,” it certainly is in bad taste. It is crude and offensive. Like Leilani Downing, a model, in her costume here from 2014. “I just got massacred by a cowboy. Note Fur is FAKE!!!” she wrote. What the hell? It is nice that no animals were harmed in the making of that costume but, really, what was she thinking? It is offensive, to be sure, to wear these costumes. But more than that, when you dress up in a costume rooted in stereotypes that are themselves rooted in the past, you are aiding the colonial project, aiding in the erasure of native peoples in the present, aiding in their consignment to the past.

And if they are part of the past, it becomes easier to dismiss the legitimate claims of native peoples as being out of time and place and, as a consequence, irrelevant. Just this week (and it is only Wednesday!) we have seen millions of baseball fans cheering for a team with a terribly offensive racist logo, read about a police killing of a young Native American woman in Washington State who was several months pregnant when she was shot, and watched heavily armed troopers, backed by a concentration of corporate and state power in North Dakota, attempt to shut down peaceful protests against an oil pipeline burrowing under sacred lands. These stories, to say the least, are not front-page news.

You should have a good time on Halloween. Soon enough, you will be freezing your asses off, trooping around the neighborhood, holding a flashlight, as your kids go door-to-door collecting candy. Soon enough you will be silently judging your neighbors for the quality of the candy they distribute. This night is for you. Have a blast. But be thoughtful, and careful. You can be creative. You can be funny. You can be iconoclastic. Hell, you can push against the limits of what is acceptable. But please keep in mind that though your costume might seem innocent, and that you may really have loved Disney’s “Pocahontas” when you were a kid, that these are manifestations of a much larger, and pernicious, dynamic. They depict native peoples as part of the past, and thus contribute to making it more difficult for many Americans to recognize the importance of native peoples’ calls for justice today.

Grief and History

When I teach Native American history, I frequently find myself describing the consequences of the policies and events we cover for children. Boarding schools, for instance, but also the many times when children die—when children were killed. I include these harrowing stories not to shock complacent students, but to try to get the kids in the class to understand more deeply the consequences of the policies, decisions, and events they have read about upon the most vulnerable people in a community, people with whom they are perhaps well-equipped to identify.

So I tell the students about George Percy. That weak and cowardly aristocrat who settled at Jamestown led a raid by an English party against the Paspahegh Indians, whose town stood a short distance upriver from that sickly fortified settlement. Percy’s soldiers took the “Queen of Paspahegh” and her children hostage but his men began to grumble. He gave in to them, threw the children overboard, and allowed his men to entertain themselves by “shooting out their brains in the water.” I tell them of the Paxton Boys’ massacre of peaceful Conestoga Indians in December 1763. The Paxton men killed fourteen of them: men, women, and a couple of children, no more than three years old. The Paxton Boys split their skulls with tomahawks, and took their scalps as trophies. This was intimate violence, acts committed at close range. To children. To babies. In order to help my students make sense of the Ghost Dance, I tell the students about the movement that occurred on the Kiowa-Comanche-Apache Reservation. Among the Kiowa ghost dancers were a lot of parents, and they danced on the snowy ground hoping to see, once again, the children who had died, innocents slaughtered by measles, whooping cough, and pneumonia. Grief lay at the broken heart of the Ghost Dance movement. And of course that grief continues. Harold Napoleon, in Yuuyaraq: The Way of the Human Being described Alaska Native communities immersed still in a grief caused by what he called “the Great Death.”

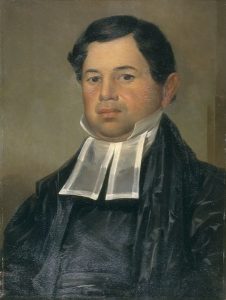

A short time ago I published a biography of Eleazer Williams, a Mohawk missionary to the Oneidas. I spent a lot of time with Williams. He struck me as a man with few principles, or as a liar, a hustler, or a confidence man. But Williams was also a man profoundly damaged by the death of his second child.

He wrote a letter to his wife in 1838. She was a Metís woman, living still along the Fox River in Wisconsin. At this point, Williams had been living apart from her for the better part of a decade. He was always traveling—Buffalo, Oneida, Albany, New York, Washington, and only occasionally back to Green Bay. This was the only letter of any length that he wrote to his wife that has survived, and in this one he began with small matters—of how the water and ice on the Fox River had done damage to the crops, he had heard. He chastised her for not having planted the potatoes on higher ground. But he also urged her to think about matters religious. Beware the shallow things. Please, he wrote to his “Dear Mary,” “Nothing in this life would make me more happy than to find that you are serving God, and living in humility, as one who is devoted to Christ and preparing for Heaven.” Focus on the important things. “Let no longer the world and its vanities be upon the upper most in your mind or thoughts—forsake them and give yourself to God and Jesus Christ who had redeemed you by his most precious blood.”

What, I wondered, was going on here? He was writing, it seemed, to a woman who had lost her faith—in religion, in him, and, I suspect, a lot of things. As I read the letter, it became clear to me why that might have been. Williams had never lacked for words, but in this letter his desperation is palpable. He would pray for her, he said. We must be a good example, he said, for the “only child we have.” I knew that Williams and his wife had a son, who would have been a teenager. “How happy it would be, should we as a family, finally by the mercy of God, to meet all, with our departed beloved Anne, in Heaven, where, we shall all be happy without end and sing praises to God for all eternity.”

Who was Anne? He had never mentioned her before. This is the only time she appeared in Williams’s papers. A dead child, presumably. It took a lot of digging. After some time in the archives, I found her. She had died in 1830, eight years before this letter. Hers was the first baptism recorded at Holy Apostles, the church Williams founded for relocated New York Indians in Wisconsin, and the first burial in the churchyard. It was in 1830 that Williams largely left home. Mary buried the child, who died when she was not quite eighteen months old, without his help.

This death haunted Williams. In the late 1840s he began to tell a story about an encounter he had with the French Prince de Joinville aboard a great lakes steamboat in 1841. In this story, Williams told Joinville as they approached Green Bay that he and his wife had an infant daughter. Joinville offered to serve as godparent. When they arrived at Green Bay, Williams learned that the baby had died several days earlier. Joinville was sympathetic, but Williams never went home. He hung out with the French prince for a couple of days. And here’s the thing: This story—Joinville, the baby—it was all a lie. It did not happen. Williams was a liar. That was easy to prove. But why this lie, about this baby?

If you study early American history, you learn how frequent the death of children actually was. Many families buried children, and I can imagine that the consequences were as emotionally devastating for many of them as it was for Eleazer Williams and his wife. New England children studying their catechisms in the early nineteenth century were warned to consider that

I, in the burial place may see

Graves shorter far than I;

From Death’s arrest no age is free,

Young children too may die . . .

My God, may such an awful sight

Awakening be to me!

O that by early grace I might

For death prepared be.”

The death of children was common.

As a historian, I find these stories sometimes difficult. I have never shared these thoughts with my friends and colleagues who teach history, but I imagine that they, too, can be overwhelmed by this history of grief, of people gone too soon. It’s heavy. My own children are all healthy. Despite my own flaws, they are fine people, better than me in so many ways. I am fortunate. But not everyone is. In a chilling article that appeared in the October issue of The Atlantic, Roger Rosenblatt reflected upon the viciousness and inhumanity he had witnessed or learned about over his long career as a war reporter. Rosenblatt told the story of Khu, a 15-year old boy who fled the war in Vietnam for Hong Kong. His parents had died, and he had nothing. They ran out of food on the ship he boarded. The captain assigned one man to knock Khu out, and then slit his throat, so that the others on board could eat him. Tears welled in the boy’s eyes, and they let him go, but they did kill another man and they ate him. Khu, Roseblatt, and his translator looked out at the lights in Hong Kong Harbor. Khu said that the lights and the boats were beautiful. That is what he was thinking. Rosenblatt asked him what else was beautiful. Khu said everything is beautiful. Sometimes even when it’s not.

I have thought of these stories today. I read Jayson Greene’s searing essay in The New York Times, entitled “Children Don’t Always Live.” Greene told the story of his daughter’s sudden, tragic death, his struggle with grief, and his continuing sadness even as he and his wife welcomed a new child, a boy who always will have a dead sister. Speaking to his young son, Greene mustered “up every drop of bravery I can: ‘It is a beautiful world,’ I tell him, willing myself to believe it. We are here to share it.”

I get that. I try to persuade my students to be hopeful and, because they are young and bright and have not seen much yet, it is not a difficult sell. Still, we cannot teach about the past without considering the pain, the grief, and the sadness that people—native and non-native alike—felt. If we want to reach our students, we need to help them feel the weight of the past, to experience those moments of brutality, violence and sadness, and those occasional moments of courage, humanity and grace. Connection, right? Reaching across the span of time, across the vast distances, in an attempt to come close to understanding the world as others experienced it.

The Lone Woman of San Nicolas Island

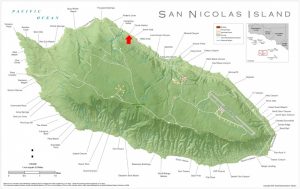

In Native America I tell the tale of the “Lone Woman of San Nicolas Island.” Thanks to some recent archaeological and historical work, we may now know more than ever before.

I grew up in Ventura, California, home of the Channel Islands National Park headquarters. Kids in my town, and I suspect around the country, learned a fictionalized version of the “Lone Woman’s” story in Scott O’Dell’s famous novel, The Island of the Blue Dolphins. In my memory, every kid had to read this book in middle school. San Nicolas is one of the Channel Islands, off of the coast of Ventura and Santa Barbara Counties, though it is owned by the United States Navy, is not part of the National Park, and is not as a result as accessible as the other Channel Islands. Nevertheless, this was part of a history that was both local and significant to me, and it was a delight to have an opportunity to include the story in the textbook.

According to the conventional story, in 1853 a party of hunters led by a Californian named George Nidever encountered an elderly Nicoleño “busily employed in stripping the blubber from a piece of seal skin which she held across the knee, using in the operation a rude knife made from a piece of iron hoop stuck into a piece of rough wood for a handle.” She welcomed the white men, who could see that she lived in a camp comprised of “several huts made of whale’s ribs and covered with brush, although it was long since they had been occupied that they were open on all sides and grass was quite high within.” She had lived there for a long time, perhaps since the uprising of 1824. The white men saw that “there were several stakes with blubber on them,” and that there “was blubber also hanging on a sinew rope.” She had baskets, and “fishhooks made of bone, and needles of the same material, lines or cords of sinews for fishing and the larger rope of sinews [which] she no doubt used for snaring seals on the rocks where they came to sleep.”

At the invitation of the hunters, she accompanied the men as they hunted otter and seals on the islands. She traveled with them for several days. When the wind began to blow too strongly, “the old woman conveyed to us by signs her intention to stop the wind.” Nidever observed that “she then knelt and prayed, facing the quarter from which the wind blew, and continued to pray at intervals during the day until the gale was over.” Nidever described a Chumash woman living her life in time with a very old rhythm.

The arrival of the woman in Santa Barbara, however, made clear how much the Chumash world had changed. Less than a century after the Portolá expedition, few Californians had seen Chumash people. The old woman became a curiosity, an exhibit for the amusement of non-Indians interested in an “extinct” people. According to Nidever, “for months after, she and her things, as her dress, baskets, needle, &c. were visited by everybody in the town and for miles around outside of it.” Chumash people were exotic enough, one enterprising ship’s captain thought, that he offered Nidever $1000 for the woman. He wanted to place her on display in San Francisco, and he was willing to split the take with Nidever. Nidever refused. He learned bits of her story. She had lost a daughter, and she had grieved for many years. It was the defining event in her life. She did not have long to live. At Santa Barbara, she fell sick five weeks after her arrival and died, Nidever curiously noted, because of “eating too much fruit.” The priests at the mission church baptized her after her death and christened her Juana Maria.

Archaeologist Steve Schwartz, according to a story that appeared in the Ventura County Star on 9 October, began digging through the notes of linguist J. B. Harrington, who visited the Islands in the early 20th century, and determined that there was much more to the story. Schwartz found in Harrington’s papers answers to a number of mysteries: Why had the woman been left alone on the island in the first place? Why, after spending several decades largely alone, did she in 1853 choose to accompany Nidever? Some stories said that when the Nicloleño were leaving the island, the woman forgot her infant and left her kin to go find the child. Schwartz thought it unlikely that a woman would forget where her infant was, and that instead the child might have been 9 or 10; a nine-year old boy wandering off seemed more plausible. She remained behind with the child. According to Schwartz, “people would come to the island, see her and try to coax her to leave, and she wouldn’t leave.” Only after this child died was she willing to go to the mainland.

And though a sort of media storm took place when the Lone Woman came ashore in Santa Barbara, newspaper research indicates that bits and pieces of her story already were circulating. She appears in an 1847 Boston newspaper, and in newspapers in India, Australia, Germany and France.

Several years ago, Schwartz was part of a team that conducted excavations on San Nicolas that he believes led to the discovery of the Lone Woman’s cave. Schwartz and his colleague Sara Schwebel are assembling a Lone Woman website developed by Channel Islands National Park that will launch later this year.

Thundersticks

David Silverman of George Washington University has already written two immensely valuable studies of native peoples. In his forthcoming study of the effects of firearms on Native America, Silverman promises to shed light on a subject that has been dealt with too simplistically by too many historians. Read about David’s exciting work here.

Ethnohistory, October 2016

The new edition of Ethnohistory includes a pair of articles that complement nicely Native America: A History. Sami Lakomaki’s “We Then Went to England: Shawnee Storytelling and the Atlantic World” critically explores native peoples’ understandings of the Atlantic World. Shawnee narratives, Lakomaki writes, “highlight the complex roles of storytelling in Native-newcomer relations and Shawnee intranational debates during a critical period when growing colonial power rapidly eroded the “middle ground” across the lower Great Lakes and political disputes factionalized the Shawnees, putting new pressures on how people constructed and forgot the past.” Also worth noting, Elsa Redmond’s “Meeting with Resistance: Early Spanish Encounters in the Americas, 1492-1524,” explores the first few decades after the beginning of the Columbian Encounter. Redmond focuses especially closely on the military components of the relationships which developed between natives and newcomers.

The new edition of Ethnohistory includes a pair of articles that complement nicely Native America: A History. Sami Lakomaki’s “We Then Went to England: Shawnee Storytelling and the Atlantic World” critically explores native peoples’ understandings of the Atlantic World. Shawnee narratives, Lakomaki writes, “highlight the complex roles of storytelling in Native-newcomer relations and Shawnee intranational debates during a critical period when growing colonial power rapidly eroded the “middle ground” across the lower Great Lakes and political disputes factionalized the Shawnees, putting new pressures on how people constructed and forgot the past.” Also worth noting, Elsa Redmond’s “Meeting with Resistance: Early Spanish Encounters in the Americas, 1492-1524,” explores the first few decades after the beginning of the Columbian Encounter. Redmond focuses especially closely on the military components of the relationships which developed between natives and newcomers.

Journal of the Early Republic

The new edition of the Journal of the Early Republic has appeared. It includes a number of pieces relevant to the material covered in Native America. You will want to take a look at Karim Tiro’s review essay covering “New Narratives of the Conquest of the Ohio Country.” Karim, a professor of history at Xavier University in Cincinnati, reviews the following books: Colin Calloway’s The Victory with No Name about St. Clair’s defeat in 1791, William Heath’s William Wells and the Struggle for the Old Northwest, and Sami Lakomaki’s Gathering Together about the Shawnees.

Lori Daggar, an assistant professor of history at Ursinus College, published an article that students might want to consult. Professor Daggar writes about “The Mission Complex: Economic Development, ‘Civilization,’ and Empire in the Early Republic.” The abstract to her article reads as follows:

The “mission complex” expanded the influence and power of the United States in the Ohio Country and beyond. It linked missionaries, humanitarians, manufacturers, federal employees, and indigenous peoples through networks of markets and capital: the material goods used in the agricultural missions offered a means both to stimulate business for eastern (and developing western) manufacturers and to develop a new consumer base in the Ohio Country. Attention to the functioning of this system, based upon free yet hierarchical relations of power, reveals how the early U.S. empire thrived off of economic growth. Paying attention to indigenous peoples’ appropriation and manipulation of the complex, moreover, reveals that some Native communities and individuals endeavored to take advantage of missionary labor, while others endeavored to facilitate their engagement with the U.S. economy by reinforcing ties with both the federal government and Euroamericans. Ultimately, analysis of the mission complex reveals that imperial state policy, as well as a myriad of Native and non-Native actors, facilitated the development and expansion of capitalist markets and forms of labor in the early republic.

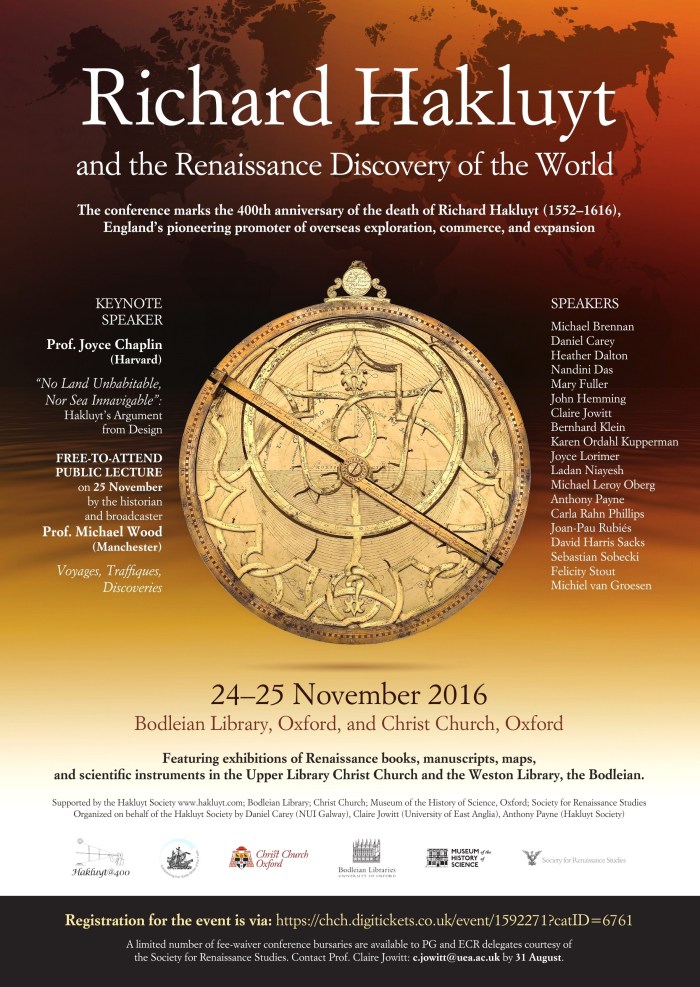

Conference Announced

Richard Hakluyt the Younger compiled the sources that allow historians to understand the encounter in the sixteenth century between English explorers, mariners, and traders, and a host of native peoples across several continents. Oxford University will host a conference sponsored by the Hakluyt Society in November commemorating the 400th anniversary of Hakluyt’s death. I will be presenting, as will Joyce

Lorimer, Carla Rahn Phillips, and many others.