Welcome Back!

It is the first week of classes at Geneseo, and as part of my spring cycle of courses, I am teaching once again my course entitled “American Indian Law and Public Policy.” The course is required for the minor in Native American Studies, fulfills the college’s Social Sciences and “Other World Cultures” general education requirements, and is an optional course for students minoring in Public Administration. Of course, it is also an elective open to history majors. The syllabus necessarily changes a bit each semester. The course is a blast to teach, and I have what looks like a good batch of students this semester. Here is the syllabus:

HIST 262 American Indian Law and Public Policy Spring 2017

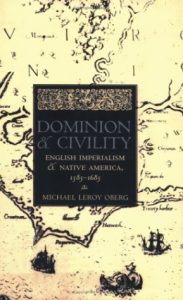

Instructor: Michael Oberg

Meetings: MWF, 12:30-1:20, Milne Library, 105

Office Hours: Monday and Wednesday, 2:30-3:30, Sturges 15 A/B

Contact: oberg@geneseo.edu

245-5730

Twitter: @NativeAmText

Website: MichaelLeroyOberg.com

Required Readings:

Stuart Banner, How the Indians Lost Their Land: Law and Power on the Frontier (2007)

Luke Lassiter, Clyde Ellis, Ralph Kotay, The Jesus Road: Kiowas, Christianity and Indian Hymns, (2002)

Steven Pevar, The Rights of Indians and Tribes, 4th edition, (2012).

Paul Chaat Smith, Everything You Know About Indians is Wrong, (2009)

Circe Sturm, Becoming Indian: The Struggle over Cherokee Identity in the Twenty-First Century, (2011).

Readings on Canvas, and

Additional Readings, for Current Events discussions and assignments:

News Articles on www.indianz.com

News Articles in Indian Country Today.

News Articles on Pechanga.net

Course Description: This course will provide you with an overview of the concept of American Indian tribal sovereignty, nationhood, and the many ways in which discussions of sovereignty and right influence the status of American Indian nations. We will look at the historical development and evolution of the concept of sovereignty, the understandings of sovereignty held by native peoples, and how non-Indians have confronted assertions of sovereignty from native peoples. We will also examine current conditions in Native America, and look at the historical development of the challenges facing native peoples and native nations in the 21st century. This course is required for the Native American Studies Minor, and counts for both the S/core and M/core general education headings. As a result, it is intended to meet the following learning outcomes:

Students Will Demonstrate:

- an understanding of knowledge held outside the Western tradition;

- an understanding of history, ideas, and critical issues pertaining to Non-western societies;

- an understanding of significant social and economic issues pertaining to Non-western societies;

- an understanding of the symbolic world coded by and manifest in Non-western societies;

- an understanding of traditional and/or contemporary cultures of Latin America, Africa, and/or Asia and the relationship of these to the modern world system;

- an ability to think globally.

And

- understanding of social scientific methods of hypothesis development;

- understanding of social scientific methods of document analysis, observation, or experiment;

- understanding of social scientific methods of measurement and data collection;

- understanding of social scientific methods of statistical or interpretive analysis;

- knowledge of some major social science concepts;

- knowledge of some major social science models;

- knowledge of some major social science concerns;

- knowledge of some social issues of concern to social scientists;

- knowledge of some political issues of concern to social scientists;

- knowledge of some economic issues of concern to social scientists;

- knowledge of some moral issues of concern to social scientists.

Your grade will be based on a number of components. Participation, an important part of your grade, is much more than attendance. I view my courses fundamentally as extended conversations and these conversations can only succeed when each person pulls his or her share of the load. You should plan to show up for class each week with the reading not just “done” but assimilated; you should plan not just to “talk” but to engage critically and constructively with your classmates. Our conversations will depend on your thoughtful inquiry and respectful exchange. Remember, as well, that conversations are most fruitful when they involve a mix of well-thought out hypotheses and tentative, partially-formed ideas. Because this course requires of you an extensive amount of reading, I am basing a large portion of your grade on your participation. This course will reward both preparation and experimentation. We are all here to learn, and I encourage you to join in the discussion with this in mind. Obviously, you must be present to participate, and once you miss more than three classes you will no longer be able to receive any credit for participation.

The individual assignments will be discussed below. The grading scale is as follows:

Participation: 100 points

Response Papers 2 papers at 25 points each 50 points

Current Events Papers 2 papers at 50 points each 100 points

Final Project 150 points

A 400-380 A- 379-360

B+ 359-350 B 349-330

B- 329-320 C+ 319-310

C 309-290 C- 289-280

D 279-240 E 239 and below.

With any of these assignments, I encourage you to visit with me during office hours if you have any questions. You should be clear on what I expect of you before you complete an assignment. The door is open. If you cannot make it to my office hours, please feel free to contact me by email, which I check several times a day. The assignments are described in detail, below.

Discussion Schedule

18 January Introduction to the Course

The United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

Reading: Banner, How, Introduction; Pevar, Rights, Ch. 1-2; UNDRIP (http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf)

20 January Native Nations in the United States

Reading: Banner, How, Introduction, Chapter 1; Articles of Confederation, Article IX; United States Constitution; Northwest Ordinance (1787); Federal Trade and Intercourse Act (1790); Treaty of Canandaigua (1794).

23 January The Marshall Court and the Definition of Native Nations

Reading: Banner, How, Chapters 2-5; Johnson v. McIntosh (1823).

https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/21/543/case.html

25 January The Removal Era

Reading: Banner, How, Ch. 6 ; Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831); Samuel A. Worcester v. State of Georgia, (1832).

https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/30/1

https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/31/515

27 January Current Events Discussion

The Reservation System

Reading: Banner, How, Ch. 7; Treaty of Medicine Lodge Creek (1867); Ex Parte Crow Dog (1883).

https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/109/556/case.html

http://digital.library.okstate.edu/kappler/vol2/treaties/kio0977.htm

30 January Policing the Reservations

Reading: Major Crimes Act (1885); US v. Kagama (1886).

https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/18/1153

https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/118/375/case.html

1 February The Policy of Allotment

Reading: Banner, How, Ch. 8; Talton v. Mayes (1896); Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock (1903); United States v. Celestine (1909).

https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/163/376/

https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/187/553/case.html

https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/215/278/

3 February Current Events Discussion

Water Rights in the Arid West

Reading: Pevar, Rights, Ch 12; Winters v. United States (1908).

https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/207/564/

First Current Events Paper Due.

6 February The Meriam Commission Report

Reading: The Problem of Indian Administration, Chapter 1 and any one chapter from Chapter 8-14.

http://www.narf.org/nill/resources/meriam.html

8 February Current Events Discussion

The Indian New Deal

Reading: Banner, How, Epilogue; Indian Reorganization Act, 1934.

https://tm112.community.uaf.edu/files/2010/09/The-Indian-Reorganization-Act.pdf

10 February The Termination Era

Reading: HCR 108; Pevar, Rights, 333-337; Tee-Hit-Ton Indians v. United States (1955).

http://digital.library.okstate.edu/kappler/vol6/html_files/v6p0614.html

https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/348/272/

13 February Williams v. Lee and the Modern Era of American Indian Tribal Sovereignty

Reading: Williams v. Lee (1959); Native American Church v. Navajo Tribal Council (1959); Pevar, Rights, Chapter 14 and pp. 329-332

https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/358/217/

http://openjurist.org/272/f2d/131/native-american-church-of-north-america-v-navajo-tribal-council

15 February The Era of Self-Determination

Current Events Discussion

Reading: McClanahan v. Arizona Tax Commission, (1973); Morton v. Mancari (1974).

https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/411/164/case.html

https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/417/535/case.html

17 February The Supreme Court’s 1978 Term and Tribal Sovereignty

Reading: US. v. Wheeler (1978); Santa Clara Pueblo v. Martinez (1978); Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe (1978).

https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/435/313/

https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/436/49/

https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/435/191/case.html

20 February Red Power

Reading: Smith, Everything (Entire Book)

22 February Congress, the Executive, and the Revolution of 1978

Reading: AIRFA; Indian Child Welfare Act; Pevar, Rights, Ch. 17

Adoptive Couple v. Baby Girl (2013)

https://www.oyez.org/cases/2012/12-399

https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/42/1996

http://www.nicwa.org/Indian_Child_Welfare_Act/ICWA.pdf

24 February Tribal Regulation of Non-Indian Activities on Tribal Land

Current Events Discussion

Reading: Montana v. United States (1981).

https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/450/544/

27 February The Powers of Tribal Governments

Reading: Pevar, Rights, Chapters 3-9

Reading: Merrion v. Jicarilla Apache Tribe (1982)

https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/455/130/case.html

1 March The Power of Tribal Governments, Continued

Current Events Discussion

Reading: Duro v. Reina (1990); Fergus Bordewich, Killing the White Man’s Indian, (CANVAS).

https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/495/676/

3 March The Power of Tribal Governments, continued

Reading: Atkinson Trading Company v. Shirley (2001); US v. Lara (2004)

https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/532/645/

https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/541/193/

6 March The Violence Against Women Act in Indian Country

Reading: NCAI Materials on VAWA (watch videos and read documents); Denver Post series, “Promises, Justice, Broken” (some of you may find this very disturbing to read)

8 March Issues in American Indian Education: Boarding Schools and their Legacy

Reading: Read any two of the papers included in Reyhner, Lockard and Gilbert, eds., Honoring Our Elders: Culturally Appropriate Approaches for Teaching Indigenous Students, (Flagstaff: Northern Arizona University Press, 2015).

http://jan.ucc.nau.edu/~jar/HOE/

10 March Issues in American Indian Education, Continued

Current Events Discussion

Reading: Continued discussion of papers in Reyhner, et. al.

Second Current Events Paper Due!

Spring Break

20 March Issues in American Indian Religion

Reading: Lassiter, Ellis and Kotay, The Jesus Road, (entire book).

22 March Issues in American Indian Religion

Reading: Pevar, Rights, Chapters 11, 13; Employment Division, Department of Human Resources of Oregon v. Smith (1990); Lyng v. Northwest Cemetery Protective Association (1988).

https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/494/872/case.html

https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/485/439/case.html

24 March Issues in American Indian Identity: The Mascot Issue

Reading: Do a Google News Search, and read about the Mascot Issue in the news sources listed above.

27 March Issues in American Indian Identity: Acknowledgment

Reading: Den Ouden and O’Brien, (Canvas)

29 March Issues in American Indian Identity

Reading: Sturm, Becoming Indian (entire book).

31 March Economic Development in Indian Country

Reading: Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development, The State of Native Nations: Conditions under US Policies of Self-Determination, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), Chapter 11. (On Canvas)

3 April Public Health in Indian Country

Reading: IHS, Trends in Indian Health, 2014 Edition, (Browse); Donald Warne, “The State of Indigenous America Series: Ten Indian Health Policy Challenges for the New Administration in 2009,” Wicazo Sa Review, 24 (Spring 2009), 7-23. (All on Canvas)

5 April Gaming

Reading: California v. Cabazon Band of Mission Indians (1987); Randal K. Q. Akee, Katherine A. Spilde and Jonathan B. Taylor, “The Indian Gaming Regulatory Act and its Effect on American Indian Economic Development” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29 (Summer 2015), 185—208 (Canvas); Pevar, Rights, Ch. 16.

https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/480/202/case.html

7 April Thee Land: The Iroquois in Western New York

Reading: Oneida Indian Nation v. County of Oneida (1974); Anne F. Boxberger Flaherty, ““American Indian Land Rights, Rich Indian Racism, and Newspaper Coverage in New York State, 1988-2008,” American Indian Culture and Research Journal, 37 (no. 4, 2013) (Canvas)

https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/414/661/case.html

10 April The Land, Continued.

Reading: City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation (2005).

https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/544/197/dissent.html

12 April The Land: Buy Back and the Cobell Settlement

Reading: 2016 Status Report, Land Buyback Program.

14 April Taxation

Reading: Pevar, Rights, Ch. 10

19 April Resistance: “You Are On Indian Land.”

Film Discussion. Watch Film in Class:

https://www.isuma.tv/the-national-film-board-of-canada/you-are-on-indian-land

21 April Resistance, Continued.

Reading: Taiaiake Alfred, Wasase, (Excerpts).

24 April What Is to Be Done?

What Is To Be Done?

Reading: Harold Napoleon, Yuuyaraq: The Way of the Human Being (1996),

26 April Catch Up

28 April Catch Up

1 May Catch Up

4 May Final Examination Period

The Assignments, Described in Detail:

Current Events Reports: A quick glance at the large number of news articles at www.indianz.com and at Indian Country Today should make it clear to you that there are constant new developments affecting the lives of native peoples and their neighbors across the nation and in Canada. You should also be able to see something of the force of history that still shapes these communities and their relationships to the United States and individual state and local governments. I expect you to try to keep up with some of this, to inform yourselves about what is going on in Native America. To that end, I expect you on two occasions during the semester to write a current event report of no more than 1200 words based on no fewer than five related news articles that you found of interest. We will discuss current events at the opening of nearly every Friday class meeting. In your brief paper you should describe the basic issues concisely and accurately, and describe the significance of the events or developments you describe in terms of what you have read and what we have discussed in class. The five papers need not be closely connected in time, nor do they need to all come from the same paper, in that you may feel free to follow a story that has developed over an extended period of time.

For your paper, you should use 11 or 12 point type, double spaced, with one-inch margins all around. You should cite accurately at the top of the paper the five or more articles you looked at. The best papers will develop an argument supported by evidence in the form of quotes from the articles you read.

Response Papers: You also will write two response papers, each worth twenty-five points, over the course of the semester. These papers will be brief meditations (approximately 1000 words) on one of the assigned readings:

Smith, Everything You Know About Indians Is Wrong, due 20 February

Lassiter, et. al., Jesus Road, due 20 March

Sturm, Becoming Indian, due 29 March

Napoleon, Yuuyaraq, due 24 April

Again, double-spaced, 11 or 12 point type. What do you see as the critical issues these books raise?

Research Project: You will complete a final project that consists of a paper of 10 to 15 pages in length, endnotes and bibliography not counted, formatted according to the guidelines spelled out in the Turabian Manual. You will play the role of an adviser to a new president (Republican or Democrat—your choice) on American Indian policy. Your paper should answer three questions: 1). What are the principal problems facing Native American communities today? 2).What are the sources of those problems? In other words, why do these problems still exist? And 3). What can and should be done about these problems within the confines of the American constitutional system?

You should have at least 20 sources for your paper.