Sometimes, when the semester begins, I think of that scene in “Back to School” where Rodney Dangerfield’s character encounters an unhinged history professor played by the great Sam Kinison. It never fails to make me laugh. Totally inappropriate for use in the classroom but, in its way, it conveys quite well that historians (and others) can disagree at times sharply in their interpretation of historical events.

When I teach my own Native American History course, I try to insert as much as possible a good dose of historiography. No more than half the students enrolled in the course in a given semester are history majors. The rest, from disciplines across the campus, are taking my class to fulfill one or more of their general education requirements. But even the history majors, in my view, are too prone to view history as a static body of knowledge, a mass of facts that I am to impart to them through lecture and discussion and that I will expect them to regurgitate on periodic examinations, rather than a dynamic field where we study continuity and change measured across time and space in peoples, institutions and cultures, and in which historians debate intensely the events that they find significant.

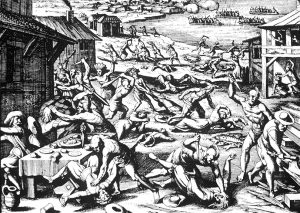

Debates about the size and origins of the aboriginal population of North America, or the consequences following from Christopher Columbus and the”Columbian Encounter,” itself a label that students can benefit from unpacking, offer an opportunity to do this early in the semester, or the nature of the Puritans’ war against the Pequots. These stories produce questions that can lead students to talk about the issues of agenda and bias, but also how evidence is used and what, indeed, constitutes reliable and valid evidence. Sharp debates among historians surround each of these issues. The Powhatan uprising led by Opechancanough in 1622, offers a fourth alternative. Today is the anniversary of that incredibly significant event.

The earliest Englishmen to write about the massacre, or uprising, or rebellion–the words themselves matter–was Edward Waterhouse. For him, the meaning of the 1622 attack was clear. The Powhatans, he wrote, were “Savages” who, “though never a Nation used so kin dly upon so small desert, have in stead of that Harvest which our paines merited, returned nothing but Bryers and thrones, pricking even to death many of their Benefactors. They were, Waterhouse continued, “miscreants,” who “put off humanity” for a “worse and more than unnatural brutishness.

dly upon so small desert, have in stead of that Harvest which our paines merited, returned nothing but Bryers and thrones, pricking even to death many of their Benefactors. They were, Waterhouse continued, “miscreants,” who “put off humanity” for a “worse and more than unnatural brutishness.

His countryman, Christopher Brooke, wrote of the Indians as “Errors of Nature, of inhumane Birth,/ The very dregs, garbage, and spawne of the Earth.” (And, No, the attack did not occur on Good Friday–that legend began as a means of conveying the innocence of the 347 colonists who died, and their sacrifice for, well, something, whether that was civilization, which was in short supply at Jamestown, or tobacco, of which there was more than enough).

You can have your students read excerpts from these documents, if you wish. Or you could have them look at how historians have made sense of the documentary record, and how they differ in their interpretations. There is Edmund S. Morgan’s indelible depiction of early Virginia, in which the events of 1622 become part of his beautifully-written exploration of American Slavery, American Freedom. Or J. Frederick Fausz’s depiction of Opechancanough’s rising as part of a “revitalization movement” triggered by the cultural arrogance of the colony’s leaders and the murder of a messianic figure named Nemattanew, or Jack of the Feathers. Fausz never published his William and Mary dissertation but there are few more influential and important works on the subject.

In the early 1990s, Frederic Gleach argued that the Powhatans reacted to English territorial expansion, and that the rising led by Opechancanough was a warning of sorts, not intended to eliminate the colonists entirely, but to teach the newcomers their place within the Paramount Chiefdom he inherited from Wahunsonacock. The anthropologist Helen Rountree, who has spent her career writing about the Powhatans, was among the earliest of the anthropologists to really try to understand the uprising in terms of Powhatan culture, and the endnotes to her books are a gold mine.

My own account, now nearly twenty years old, looked at environmental conflict between natives and newcomers, and the genocidal violence that resulted from that rivalry. The Virginia  Company’s promoters wanted originally peace and order along the early Anglo-American frontier, for hostile natives would not allow the English to profit, establish a secure foothold on American shores, or spread Christianity. Colonial promoters tended to believe that native peoples could become more like them, but they could not control the environmental conflict. Out of this conflict came warfare, and out of that warfare came racist beliefs about native peoples like those expressed in the poetry of Christopher Brooke. Articles by historians like Fred Fausz and Alden T. Vaughan, and the work of archaeologists like Martin Gallivan, can further enrich the discussion.

Company’s promoters wanted originally peace and order along the early Anglo-American frontier, for hostile natives would not allow the English to profit, establish a secure foothold on American shores, or spread Christianity. Colonial promoters tended to believe that native peoples could become more like them, but they could not control the environmental conflict. Out of this conflict came warfare, and out of that warfare came racist beliefs about native peoples like those expressed in the poetry of Christopher Brooke. Articles by historians like Fred Fausz and Alden T. Vaughan, and the work of archaeologists like Martin Gallivan, can further enrich the discussion.

The historians, anthropologists, and archaeologists who write about this topic to a great extent rely upon the same sources, but we disagree at times intensely about what they mean and the stories that those sources tell. (The bibliography in the back of Karen Ordahl Kupperman’s first book Settling with the Indians is still a tidy and convenient listing of all the published primary sources by Englishmen who observed the Powhatans at first hand).

And when our students come to us from high schools where the amount of time available for history and “Social Studies” has been reduced significantly, and the coverage of Early American history has been given especially short shrift, and Native American history is covered not at all, they cannot be faulted for arriving with little understanding of how history works, or does not work, as a discipline. They know little about what historians do, how we do it, the relationship of our discipline with anthropology, geography, and archaeology, and why all of this matters to us as much as it does.