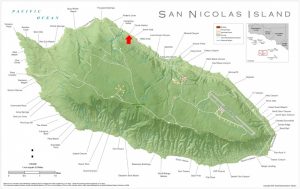

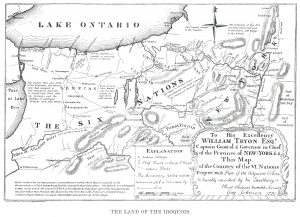

I like to show this map to my students. It is the Tryon map of the Six Nations, drawn five years before the colonis ts imperial officials hoped to control declared their independence. I ask my students, when they look at it, to forget all that they know about the subsequent history of the Empire State. Look at this map, drawn at one point in time. “Read it like a text. What do you see?”

ts imperial officials hoped to control declared their independence. I ask my students, when they look at it, to forget all that they know about the subsequent history of the Empire State. Look at this map, drawn at one point in time. “Read it like a text. What do you see?”

It’s such an obvious question that there is usually a brief silence. So I ask them to look at the map and tell me, “what, on this map, is New York? Where on this map is New York?” We talk, and quickly it becomes apparent. You cannot miss it. New York, as a geographic entity, did not exist much past Schenectady, and much beyond the Hudson River Valley. Much of what we call the New York today was, in 1771, “The Land of the Six Nations,” Iroquoia.

It is helpful to keep this in mind, because a large part of the imperial project, the core of what many scholars now call settler colonialism, was the erasure of native peoples from the American landscape, either through assimilation or annihilation. The settlers will expand, and the Indians disappear, their disappearance itself legitimizing the settlers’ claim to the land. Indians are always part of the past, always in the process of disappearing, of being swept into the dustbin of history.  They are erased, the settler state’s claims to sovereignty legitimatized, and the concerns of native peoples today more easily dismissed.

They are erased, the settler state’s claims to sovereignty legitimatized, and the concerns of native peoples today more easily dismissed.

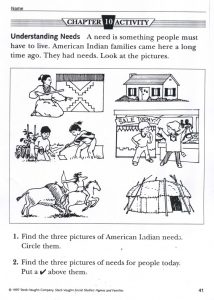

If you are a student, try this exercise. Ask some of your classmates to define an Indian or Native American. Have them tell you what comes to mind when you mention the word “Indian” or the phrase “Native American.” Play with them a word association game. In New York State, where I live, occasionally a student will mention gaming or smoke shops, but by and large the images they will conjure will be drawn from the past. It is something that many of us are taught from a very young age. Find “three pictures of American Indian needs” in the assignment here. The dutiful child will highlight the wigwam, the bison, the blanket weaver. Now “find the three pictures of needs for people today.” Erasure. Indians as part of the past.

smoke shops, but by and large the images they will conjure will be drawn from the past. It is something that many of us are taught from a very young age. Find “three pictures of American Indian needs” in the assignment here. The dutiful child will highlight the wigwam, the bison, the blanket weaver. Now “find the three pictures of needs for people today.” Erasure. Indians as part of the past.

So when you dress up in an “Indian Costume,” it certainly is in bad taste. It is crude and offensive. Like Leilani Downing, a model, in her costume here from 2014. “I just got massacred by a cowboy. Note Fur is FAKE!!!” she wrote. What the hell? It is nice that no animals were harmed in the making of that costume but, really, what was she thinking? It is offensive, to be sure, to wear these costumes. But more than that, when you dress up in a costume rooted in stereotypes that are themselves rooted in the past, you are aiding the colonial project, aiding in the erasure of native peoples in the present, aiding in their consignment to the past.

And if they are part of the past, it becomes easier to dismiss the legitimate claims of native peoples as being out of time and place and, as a consequence, irrelevant. Just this week (and it is only Wednesday!) we have seen millions of baseball fans cheering for a team with a terribly offensive racist logo, read about a police killing of a young Native American woman in Washington State who was several months pregnant when she was shot, and watched heavily armed troopers, backed by a concentration of corporate and state power in North Dakota, attempt to shut down peaceful protests against an oil pipeline burrowing under sacred lands. These stories, to say the least, are not front-page news.

You should have a good time on Halloween. Soon enough, you will be freezing your asses off, trooping around the neighborhood, holding a flashlight, as your kids go door-to-door collecting candy. Soon enough you will be silently judging your neighbors for the quality of the candy they distribute. This night is for you. Have a blast. But be thoughtful, and careful. You can be creative. You can be funny. You can be iconoclastic. Hell, you can push against the limits of what is acceptable. But please keep in mind that though your costume might seem innocent, and that you may really have loved Disney’s “Pocahontas” when you were a kid, that these are manifestations of a much larger, and pernicious, dynamic. They depict native peoples as part of the past, and thus contribute to making it more difficult for many Americans to recognize the importance of native peoples’ calls for justice today.