I recently read Colin Calloway’s book on The Indian World of George Washington, and that got me thinking about two very different depictions of our nation’s first President. I write about the Senecas, with whom these particular depictions originate, in Native America. In the late 1790s, the great Seneca prophet Handsome Lake experienced a series of visions that became the basis of the Gaiwiio, the good news of peace and power, the “old time” religion still practiced by many Haudenosaunee Iroquois traditionalists in New York State and  Canada. This was a critical moment in Seneca history, and the emergence of this gospel, and Handsome Lake’s message, was one of enormous significance, bringing hope and an explanation for their historical experience to Haudenosaunee peoples. As related in the 1850s to the early anthropologist Lewis Henry Morgan by the Tonawanda Seneca Jemmy Johnson, George Washington “stood preeminent above all of the white men” because “of his justice and benevolence to the Indians.” Johnson told Morgan that the Senecas believed “that the Great Spirit had received” Washington “into a celestial residence upon the plains of heaven, the only white man whose noble deeds had entitled him to this heavenly favor.” The only one. Not in paradise, but just outside. Washington resided there, silent and content. “No word ever passes his lips. Dressed in his uniform, and in a state of perfect felicity, he is destined to remain through eternity in the solitary enjoyment of the celestial residence prepared for him by the Great Spirit.”

Canada. This was a critical moment in Seneca history, and the emergence of this gospel, and Handsome Lake’s message, was one of enormous significance, bringing hope and an explanation for their historical experience to Haudenosaunee peoples. As related in the 1850s to the early anthropologist Lewis Henry Morgan by the Tonawanda Seneca Jemmy Johnson, George Washington “stood preeminent above all of the white men” because “of his justice and benevolence to the Indians.” Johnson told Morgan that the Senecas believed “that the Great Spirit had received” Washington “into a celestial residence upon the plains of heaven, the only white man whose noble deeds had entitled him to this heavenly favor.” The only one. Not in paradise, but just outside. Washington resided there, silent and content. “No word ever passes his lips. Dressed in his uniform, and in a state of perfect felicity, he is destined to remain through eternity in the solitary enjoyment of the celestial residence prepared for him by the Great Spirit.”

It is quite an image, and one difficult to reconcile with the man known by many Indians as the “Town Destroyer,” a name originally claimed by his great-grandfather for the fighting he did along the Potomac frontier in the 1670s, and which our Washington appears to have appropriated and used when it served his purposes. From his birth to his death, Washington lived in a world carved out of Indian land. Washington spent nearly his entire career thinking about and fighting against native peoples, engaging them in diplomacy, and laying plans and conceiving of policies to acquire Indian lands for himself, for his fellow investors, and, later, for his nation. Indeed, Washington was instrumental in the dispossession of native peoples. The country he played so fundamental a role in founding rose on lands lost by native peoples.

During the colonial period, during the era of the Revolution, during the Confederation and under the new Constitution, Americans could disagree intensely over the conduct of Indian policy. This long-running debate, however, for white Americans was always over means, not ends. The debate boiled down to defining the nature of the Indians’ defeat.

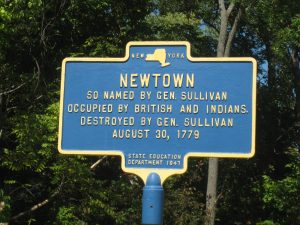

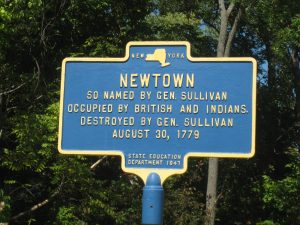

Washington’s treatment of Native America makes clear that the answer would involve violence. During the Revolution, Washington ordered invasions of the Iroquois that resulted, if we choose to believe Haudenosaunee voices, in the rape and murder of Onondaga non-combatants by New York militiamen following Colonel Goose Van Schaick. It resulted in what can justly be called war crimes against Senecas and Cayugas as well the destruction of their crops and orchards, and dozens of towns in 1779 as part of the infamous  Sullivan campaign. Washington hoped that Sullivan’s men would “distract and terrify” the Indians and, in Washington’s own words, “extirpate them from the Country.” Sullivan’s soldiers drank a toast promising, among other things, “civilization or death to all American savages.”

Sullivan campaign. Washington hoped that Sullivan’s men would “distract and terrify” the Indians and, in Washington’s own words, “extirpate them from the Country.” Sullivan’s soldiers drank a toast promising, among other things, “civilization or death to all American savages.”

As my kids sometimes say, “That’s pretty racist.” Not a pretty picture at all. So how did this guy end up outside the Senecas’ heaven, close to, but not quite inside, paradise?

To best answer that question, I suggest that we flip the narrative, and try to look at these important events in American history as native peoples might have experienced them. As I point out in Native America, we can start with the words we use.

Words like ‘Indian,” for example, or phrases like “Native American,” of course are flawed. They obscure more than they reveal, and they would have meant little to peoples whose names for themselves often translated as “people” or “the real people,” or “the real human beings.” But the problem with words goes even deeper than this. Too many historians, for too long, have relied upon flawed dichotomies: there was a “pre-contact” or “prehistoric” period that came before “contact” and before the arrival of Europeans ushered in the “historic” era. Native peoples obviously had long histories on this continent before Europeans arrived. They interacted and exchanged with and fought against native neighbors near and far, and these contacts bred a host of cultural practices that pertained to their “contact” with others. They did not simply drop these aboriginal practices when Europeans arrived.

Language can be difficult, and words tricky things.

Colonists “settle” but Indians do not: they are depicted nomads who wander and roam when they in places were more fixed and tied to place than the newcomers. Europeans plant crops, but Indians do not, according to conventional wisdom; colonists serve as soldiers while native peoples fight as warriors. Language can emphasize difference, and an emphasis of difference can be misleading, for example, because it might make violence seem inevitable, or reinforce racial and racist stereotypes. In reality, the differences between natives and newcomers at the outset might not have been as great as our flawed language leads us to believe. Both, for example, relied upon an agriculture centered upon corn to stay alive. Both supplemented their agricultural produce with sources of protein they acquired systematically. Native peoples, for instance, managed forests, burned underbrush, and generated new growth that attracted game that hunters could more easily harvest. Newcomers, meanwhile, turned their livestock loose and allowed it to forage and fend for itself. When the settlers got hungry, they went out into the woods to hunt down their nearly feral cattle and hogs.

Some more words. The “Founding Fathers,” the patriots, and white settlers who encroached on native peoples’ lands, Indians saw not as freedom fighters but as “perfidious cruel rebels” and, tellingly, as “white savages.” They referred to them not as champions of liberty but as “Butchers,” and “Killers,” and “Madmen.” They called them “Big Knives” or “Long Knives,” names that chillingly reflected the violence with which they were associated. Native Americans in this part of the country in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries feared that Americans acted with genocidal intent, and they said it again and again and again. One solution to the Indian question, for some white settlers, you see, was extermination, and groups of white Americans expressed that desire and acted on it in ways that confirmed the nightmares of native peoples. You can think of the murder and mutilation of children carried out by the Paxton Boys late in 1763, acts of horrific violence that have brought my students to the edge of tears. Children murdered by white vigilantes armed with tomahawks.

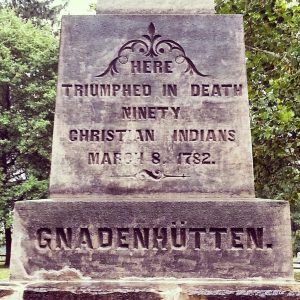

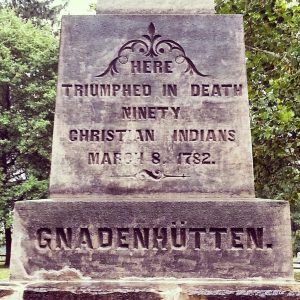

Or the massacre at Gnaddenhutten, 1782. Gnaddenhutten– “The Houses of Mercy.” That’s what that name means. No mercy there for the Christian Indians who lived and prayed and worked there. The soldiers from Pennsylvania surrounded the Christian Indians at  Gnaddenhutten. They had them at their mercy. So they held a vote on whether or not to kill the one hundred Christian Indians they had taken captive. This was, for many native peoples, what American democracy looked like. I have written about the massacre at Gnaddenhutten on this website. It is a devastating history. One could write a history of Native Americans that uses the violence meted out on native children as the vehicle driving the narrative, from the earliest period to the present.

Gnaddenhutten. They had them at their mercy. So they held a vote on whether or not to kill the one hundred Christian Indians they had taken captive. This was, for many native peoples, what American democracy looked like. I have written about the massacre at Gnaddenhutten on this website. It is a devastating history. One could write a history of Native Americans that uses the violence meted out on native children as the vehicle driving the narrative, from the earliest period to the present.

I tell my students about these violent episodes. These events allow us to mess around with words. Murder at Gnadenhutten becomes an expression of democracy. Frontier settlers become savages. I try to decenter things, to upset expectations. And I think we need to do this if we are to understand why so many native peoples so forcefully and effectively resisted the newly independent United States. And, also, how the Senecas,–the victims of a brutal invasion ordered by Washington and by acts of vigilante justice for decades thereafter– might pass a silent George Washington, the man who ordered the burning of their towns and forced them to flee their homeland, on their way into heaven.

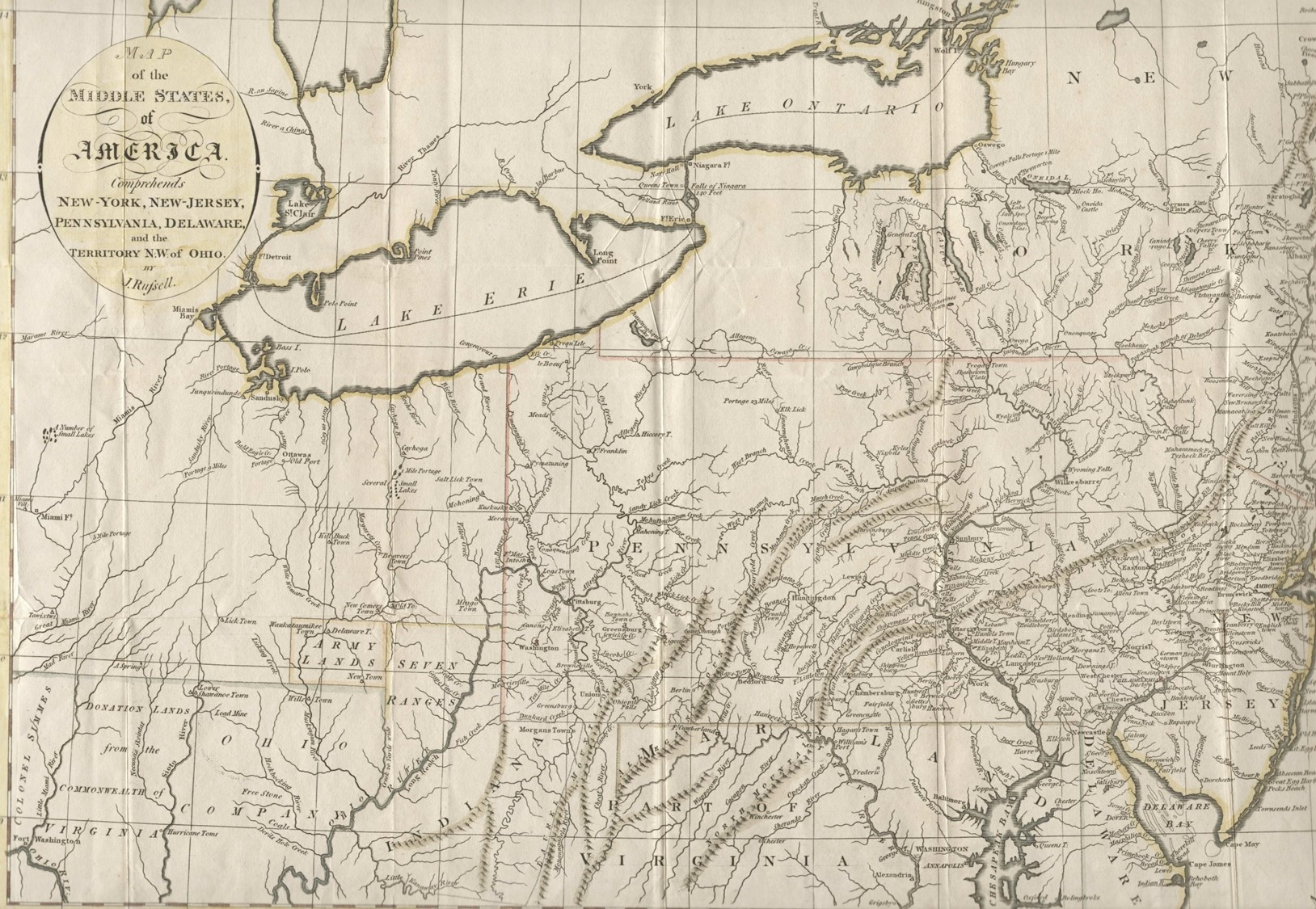

After the war, after he resigned his commission, Washington’s advice was sought out and given on Indian affairs. In a letter he wrote to James Duane of New York in the fall of 1783, he called for effective and meaningful oversight of the settlement of the western territories. He always had distrusted squatters, and feared the unregulated expansion of white settlement. He wanted peace and order on the frontier, to acquire land without conflict. “To suffer a wide extended Country to be over run with Land Jobbers, Speculators, and Monopolisers or even scatter’d settlers,” he wrote “is pregnant of disputes with the Savages, and among ourselves, the evils of which are easier, to be conceived than described.” Native peoples, he asserted, had sided with Great Britain against the American states and all good advice. A “less generous people” than we, he said, would drive them out. Recognizing that this would involve a renewal of conflict with native nations that had been battered but not defeated during the war, Washington suggested that the Indians be told that the past will be forgotten. The United States, however, whether they liked it or not would “establish a boundary line between them and us beyond which we will endeavor to restrain our people from hunting, or settling, and within which they shall not come, but for the purpose of Trading, Treating, or other business unexceptionable in its nature.” Indians would give up lands in the process, to the United States or to the states with the best claim to those lands. The sale of Indian lands allowed states to pay their soldiers. The sale of Indian lands allowed New York to abstain from taxing its citizens before the War of 1812. Indian dispossession made New York the empire state.

But the result of these Confederation policies was chaos. The Articles of Confederation, the new nation’s first constitution, established a limited government in which the states retained all rights they had not explicitly granted to the national government. In Article IX of the Articles, which listed Congressional powers, the states granted the national government the “sole and exclusive right and power” of “regulating the trade and managing all affairs with the Indians, not members of any of the States, provided that the legislative right of any State within its own limits be not infringed or violated.” Who might these Indians be? New York? Virginia? North Carolina? Georgia? This crazy ambiguity allowed aggressive states like North Carolina, Georgia, and New York, and even entities like the upstart “State of Franklin,” to conduct their own Indian policies, negotiate their own treaties, and extract their own land cessions, at times in defiance of Congress and, in the case of Georgia, at the point of a gun. Land speculators, squatters, cattle rustlers, timber cutters, state politicians, congressional commissioners, and Indian killers—they all assaulted the Native American estate. And Congress itself, in the treaties it convened with Indian nations it claimed to have defeated, operated on a “conquest theory,” asserting that because the Indians had aligned themselves with Great Britain, and Britain had lost, so too had the Indians. Native peoples seethed with resentment at the treatment they received from national and state officials during the Confederation, as congressional commissioners cast aside long-established protocols for conducting diplomacy, and thumped Indian leaders in the chest demanding cessions.

This could not stand, for these native nations maintained the capacity to resist. Washington certainly supported efforts to replace the Articles of Confederation with a more powerful central government based on the imperial model. He agreed with the Virginians who saw the faults in the Articles. Like James Madison. In his white paper laying out the “Vices of the Political System of the United States,” Madison placed as number two on his list “encroachments by the States on Federal authority,” and he gave as an example “the wars and treaties of Georgia with the Indians,” state aggressions against the powerful Creeks that threatened the entire Southern frontier. Washington frequently expressed a similar complaint.

The new constitution of 1787 eliminated the ambiguity of the Articles of Confederation. In Article I, Section 8, we the people granted to Congress power “to regulate Commerce with Foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian tribes.” That’s it. That is all it says.

To flesh out that spare language, Congress in 1790 passed the first of several Indian trade and Intercourse Acts. (The first was enacted in 1790, the last in 1834). The law, which reflected perfectly the views of Washington and his secretary of War Henry Knox about the conduct of Indian policy, provided rules governing those instances when native peoples and newcomers came into contact. Legal land sales required the oversight of an appointed federal commissioner and the subsequent ratification of the transaction by the Senate. Trade without a license obtained from federal agents was prohibited.

It is important to say a few words about this important piece of legislation, the nation’s first Indian law. Washington, in a letter written to the Senecas in December of 1790, saw the new law as a watershed. The Iroquois had indeed lost much to the State of New York during the Confederation years but now, he wrote, “the case is entirely altered—the general government only has the power to treat with the Indian nations, and any treaty formed and held without its authority will not be binding.” The Trade and Intercourse Act would provide “security for the remainder of your lands.” The United States, he continued, “will never consent to your being defrauded,” “will protect you in all your just rights,” and “considers itself bound to protect you in all the lands” you still possess. Washington never claimed any power over the internal workings of native nations. Nor did the Constitution grant to the national government any powers over the internal workings of native nations. Sovereign native nations were a force Washington and his contemporaries recognized.

Washington needed a peaceful and orderly frontier, but the government he commanded was a tiny thing. The total number of non-uniformed employees of that national government in 1801, the first year for which we have good figures, was less than three thousand, and the vast majority of these worked in customs or other revenue-related functions, or the postal service. The number of federal officials in all of New York working in Indian affairs, for instance, could be counted on one hand. The government and its agents, then, could do little to curb encroachment, or prevent theft, or timber cutting or cattle rustling, by white people in Indian country. Even if the will was there—and that is a matter that is debatable—the institutional apparatus was not.

The states continued to purchase Indian lands. Settlers continued to encroach. Conflict erupted in Georgia, the Carolinas, and in the Ohio Country, where growing numbers of militant native peoples came together in a spirited resistance against American expansion. This territorial and physical aggression unquestionably frustrated Washington, but aware fully that power claimed but not exercised was power lost, he largely held his tongue. Controlling state governments was one thing; controlling the violence of settlers still another. Thirteen Senecas, to cite one example from some of my own work, were murdered by white frontiersmen between 1784 and 1790 and probably another half-dozen more in the couple of years that followed that. Native peoples found their life, liberty, and property in jeopardy. For them, these were times that tried men’s souls.

And here’s the thing. These grievances were significant, and Washington understood this. He mentioned them in his annual messages to Congress. He worked to negotiate treaties to resolve them, always looking for additional cessions of land. Indians in the so-called Northwest Territory shared many of these grievances. So while the government hoped to extract cessions and purchase the land upon which settlers settled and squatters squatted, native peoples increasingly committed themselves to protecting their homelands by force. So they were ready when, in September of 1790, General Josiah Harmar led a force of 1450 regular soldiers and Kentucky militiamen out against the native towns along the Wabash and Maumee rivers in what today is the state of Indiana. Native peoples from many nations—Shawnees, Miamis, Ottawas, Potawatomis, Weas, and Kickapoos—ambushed Harmar’s force along the Maumee and killed 180 of his men. The defeated American force returned home by the end of October.

The defeat of Harmar’s invasion emboldened those native peoples willing to resist American forces, and swelled their ranks. Potawatomis and Shawnees, along with Delawares and Miamis, attacked a settlement called Dunlap’s Station just north of Cincinnati in January of 1791, while Potawatomis joined with Ottawas and Chippewas to attack targets elsewhere along the Ohio. By the spring, land speculators in the Ohio country complained that they found it difficult to recruit prospective settlers. “The Indians kill people so frequently,” they wrote, “that none dare stir into the woods to view the country.”

Native peoples had their own fears, of course. When Kentucky militiamen attacked a cluster of villages in northern Indiana where Potawatomis and many other native peoples lived, they threatened them with extermination. If native peoples refused to make peace, Brigadier General Charles Scott said, “your warriors will be slaughtered, your towns and villages ransacked and destroyed, your wives and children carried into captivity.” Many of those who lived in the Ohio country saw in the United States, whatever its claims to desire peace, a truly existential threat, the menace of genocide.

Meanwhile, Congress had already laid plans for another military invasion to take place in 1791. Arthur St. Clair, whose chief qualification was his seniority, led American forces into the Miami River Valley in September. Most of his soldiers were militiamen, poorly trained and poorly supplied. Before dawn on November 4, a force that consisted of Potawatomis, Shawnees, and large numbers of others—Ottawas, Chippewas, Wyandots, Mingos, Delawares, Miamis, and a few Chickamauga Cherokees—attacked St. Clair’s much larger force. The soldiers panicked and ran. Over 640 soldiers were killed or captured or unaccounted for. Another 250 were wounded. Fewer than 500 men made it to safety unharmed. They killed only a small number of Indians in the largest defeat ever suffered by American military forces at the hands of native warriors. Twenty percent of the American military had been wiped out in one day.

By 1792, native peoples from many nations had gathered at a site called the Glaize, near today’s Defiance, Ohio. There they reflected upon the meaning of their victories over the American forces. Native peoples with grievances against the Americans settled there, and their numbers included Potawatomis, Shawnees, Delawares, Miamis, Sacs, Foxes, Ottawas, Hurons, Munsees, Conoys, Mingos, and Cherokees and Creeks. The presence of the southern nations showed that the diplomatic connections between militants north and south remained strong. American agents feared that the powerful and well-armed Creeks and Chickamaugas would join with the Shawnees and other northerners to attack American settlements. The Indians gathered at the Glaize, according to the Shawnee leader Painted Pole, would unite to resist further invasions. The inability of the American government to control its vicious backcountry settlers, and its own rapacious desire for Indian land, had unified its many enemies into a powerful native force.

With the British still occupying forts on American soil, and imperial officials brazenly discussing the policy of creating a neutral Indian barrier state north of the Ohio River, with native peoples hostile towards the United States insulating Britain’s holdings from American expansion, the situation was dire indeed. It is stunning. Britain hoped to snap off that part of the United States north of the Ohio River to create a neutral Indian barrier state. If powerful groups like the Senecas, with the potential to receive easily British arms and ammunition from Fort Niagara joined with the victorious northwesterners, the entire frontier could be set ablaze. Washington ordered another invasion of the Ohio Country. Late in the summer of 1794, American general Anthony Wayne led his force of 3000 soldiers toward the Maumee Valley. There, on August 20, he defeated the confederated tribes at the Battle of Fallen Timbers. Although casualties were roughly the same on each side, the Americans took the field, and razed the Indian towns. The fleeing warriors headed toward the British post at Fort Miami. British agents had remained active in the Northwest since the close of the Revolution, and they had armed and encouraged the natives’ resistance to American expansion. Now, however, they kept closed the gates to their forts and refused to fire upon the pursuing Americans. Once again, the British abandoned their native allies and demonstrated, if the point still required demonstration, that native peoples in the Old Northwest needed the British more than the British needed them.

They now had no choice but to make peace with the United States. A year after the battle, at Greenville, the Potawatomis, Shawnees, Delawares, Ottawas, Chippewas, Miamis, Weas, Kickapoos, Piankashaws, and Kaskaskias agreed to a peace that “shall be perpetual … between the United States and Indian tribes.” They paid as the price of that peace a massive cession of lands to the United States. The confederated tribes gave up tracts of land in Indiana and Illinois, and, more significantly, all of southern and eastern Ohio.

The Treaty of Greenville revealed the sort of changes that the President and the Secretary of War hoped to bring to their defeated enemies. Each of the nations signing the treaty would receive an annuity, a yearly payment of money and other items the tribe could use to supply its wants. If the tribes should “desire that a part of their annuity should be furnished in domestic animals, implements of husbandry, and other utensils convenient for them, and in compensation to useful artificers who may reside with or near them, and be employed for their benefit,” they need only to inform the federal agent stationed nearby and “the same shall at the subsequent annual deliveries be furnished accordingly.” The United States would thus see to the civilization of the Indians, by transforming them from wandering hunters into settled farmers on the American model. Because farming required less land than the hunt, the thinking went, more land soon would be opened for white settlement and expansion. To make this argument, of course, required the Americans who wrote the treaties, like Wayne, and those who ratified and proclaimed them, like the members of Senate and the president, ignore the vast Indian cornfields that American forces destroyed, or the herds of cattle and swine that even now native peoples relied upon for food. To save the Indians, Americans would civilize them, and civilization required that they live upon less land. Americans took native land in the name of helping native peoples become civilized. Taking, as one historian put it, became giving.

There were still the problems in Iroquoia that caused Senecas to contemplate joining the Indians to their west. Their disaffection was real, the threat they posed to the United States significant. As Anthony Wayne invaded the Maumee valley, the American commissioner Timothy Pickering met with the Six Nations at Canandaigua in western New York. He hoped to resolve long-standing difficulties with the Senecas. Their lands formed the central issue at the council. Through the Treaty of Canandaigua, signed on November 11, 1794, Pickering and the Senecas redefined the boundaries of the Seneca estate. The new western boundary of their lands ran “along the river Niagara to Lake Erie.” This gave to the Senecas access to the river and the islands and access to British Canada to their west, a freedom, they hoped, that gave them an outlet and the opportunity to avoid the fate of other encircled Indian tribes. The Senecas did not wish to become “mere makers of baskets and brooms.” This was an important concession. The ability to move through space, to interact with Haudenosaunee communities distant from them, was of immense importance to Iroquois peoples. Pickering also agreed to pay to the Senecas “a quantity of goods to the value of ten thousand dollars,” and, further, that “with a view to promote the future welfare of the Six Nations,” an annuity of $4500.

As with the treaty negotiated eight months later at Greenville, the United States sought to civilize the Six Nations and transform them into farmers on an American model. To the Senecas, however, the 1794 Treaty of Canandaigua recognized their sovereignty. This is why it is so critical. It is why they honor Washington still and commemorate the treaty every year. Pickering, on the president’s behalf, pledged that the United States would never claim the Senecas’ lands, “nor disturb the Seneka nation, or any of the Six Nations, or their Indian friends residing thereon and united with them, in the free use and enjoyment thereof.” The Free Use and Enjoyment of their lands: it is a critical phrase. They could, they hoped, live upon their lands without the interference of outside authorities, and with the protection of the United States against unlawful intrusion. The treaty, the Senecas believed, recognized their right to exist upon their ancestral lands as a nation free from outside interference. It recognized their nationhood.

1794, by any standard, was a momentous year in the history of the Early Republic. There’s the Whiskey Rebellion, and the foreign policy problems occasioned by war between France and Great Britain. And Indian affairs. That year, Washington said that he had hoped to oversee the orderly expansion of American settlement while pursuing a policy “calculated to advance the happiness of the Indians and to attach them firmly to the United States.” He wanted peace, and to see to the “civilization” of native peoples. To this end, congress enacted and he signed the Trade and Intercourse Acts, designed to ensure order along the frontier and peace in relations between native peoples and the citizens of the young republic. He abandoned the conquest theory advanced by the Continental Congress in the immediate aftermath of the Revolution for a system based on treaties that, he hoped, would regulate American expansion while guaranteeing native nations the lands that they did not cede—at least until the next treaty council.

Yet Washington that same year lamented “the insufficiency of the existing provisions of the laws toward the effectual cultivation of peace with our Indian neighbors.” By 1796, the final year of his presidency, Washington still hoped to restrain “the commission of outrages upon the Indians,” but he feared that “scarcely anything short of a Chinese wall, or a line of troops, will restrain Land jobbers, and the encroachment of settlers upon the Indian territory.”

A Chinese Wall was out of the question.

The policies advanced by Henry Knox and he failed to achieve their cardinal goals for a number of reasons. Many native peoples, of course, already considered themselves civilized, and saw little attractive in the arrogant assumption that they must abandon their culture in order to survive. Others dressed like their white neighbors, bore Anglo-American style names, and lived in American-style housing. Many of them spoke English. They may even have listened to missionaries who worked to save their souls. Many already were members of Christian congregations. But they borrowed selectively, took what they wanted, and they lived on the margins of American society in communities of their own making. Though they incorporated substantial amounts of Anglo-American material culture into their lives, they remained quietly indifferent to what many Americans felt they had to offer native peoples.

Those native peoples who did work with the Americans—the leaders who, hoping to avoid the horrors of wars they feared they could not win, or the continuing loss of their lands—signed treaties guaranteeing them all that remained until they were ready to sell. They may have attended to the missionaries, accepted agricultural implements and livestock, and tried to make changes in their ways of living because they believed that doing so offered the best chance for their people to survive. But making these changes raised all sorts of challenges.

The frontier, we must remember was a violent and at times a frightening place. Many settlers living on war-ravaged frontiers simply could not trust their Indian neighbors, no matter how small a sliver of their original lands they retained. Settlers in the Ohio country, for example, experienced the horrors of warfare just as did Indians. Some of them witnessed the death of friends and neighbors in Indian attacks. More of them heard horrifying stories of Indian attack. These settlers had occasion to fear Indians and they found in their fears justification for horrible acts of terror. They could, as did those Ohio country settlers in 1782, conclude that the singing of psalms by Christian Indians at the Moravian mission at Gnadenhutten was not the expression of praise for a peaceful and loving God, but the ranting and boasts of savages who had wet their hands in the settlers’ blood.

These acts of violence, along with the failure of the young republic to control its land-hungry settlers, and the continued suffering in many native communities, gave encouragement to those leaders who called for an armed resistance against the Americans. By 1794, much of this resistance had collapsed, and native peoples paid an enormous price for it. Warfare, and the resulting dislocation, devastated native communities. The Cherokees surrendered over 20,000 square miles of their territory. The Six Nations, combined, lost much more, and the population of both nations declined significantly between 1776 and 1794. The birth of the new republic, an “empire for liberty” in Jefferson’s view, proved catastrophic for many native peoples. Washington always wanted to dispossess Indians, to acquire their lands. He hoped to do so peacefully, through treaties, with a minimum of cost and violence. Unlike, say, Jefferson, who wrote at length about native peoples, he never gave much thought to their history and culture. Native peoples were, for him, an obstacle, and a problem to be solved. A creature of empire, his solutions were imperial, even if his was an imperialism tempered by his limited control over his countrymen, and a recognition of the power, and the nationhood, or native peoples. Some of these natives succeeded against long odds in remaining upon their lands. That was the case with the Senecas and the Tuscaroras I visited yesterday, who in their casino enterprises, their tribal businesses, in their programs for cultural preservation, continue to assert their untrammeled right to the “free use and enjoyment of their lands” as their departed relatives move past Washington, who signed the treaty that recognized their enduring nationhood, on their way into paradise.

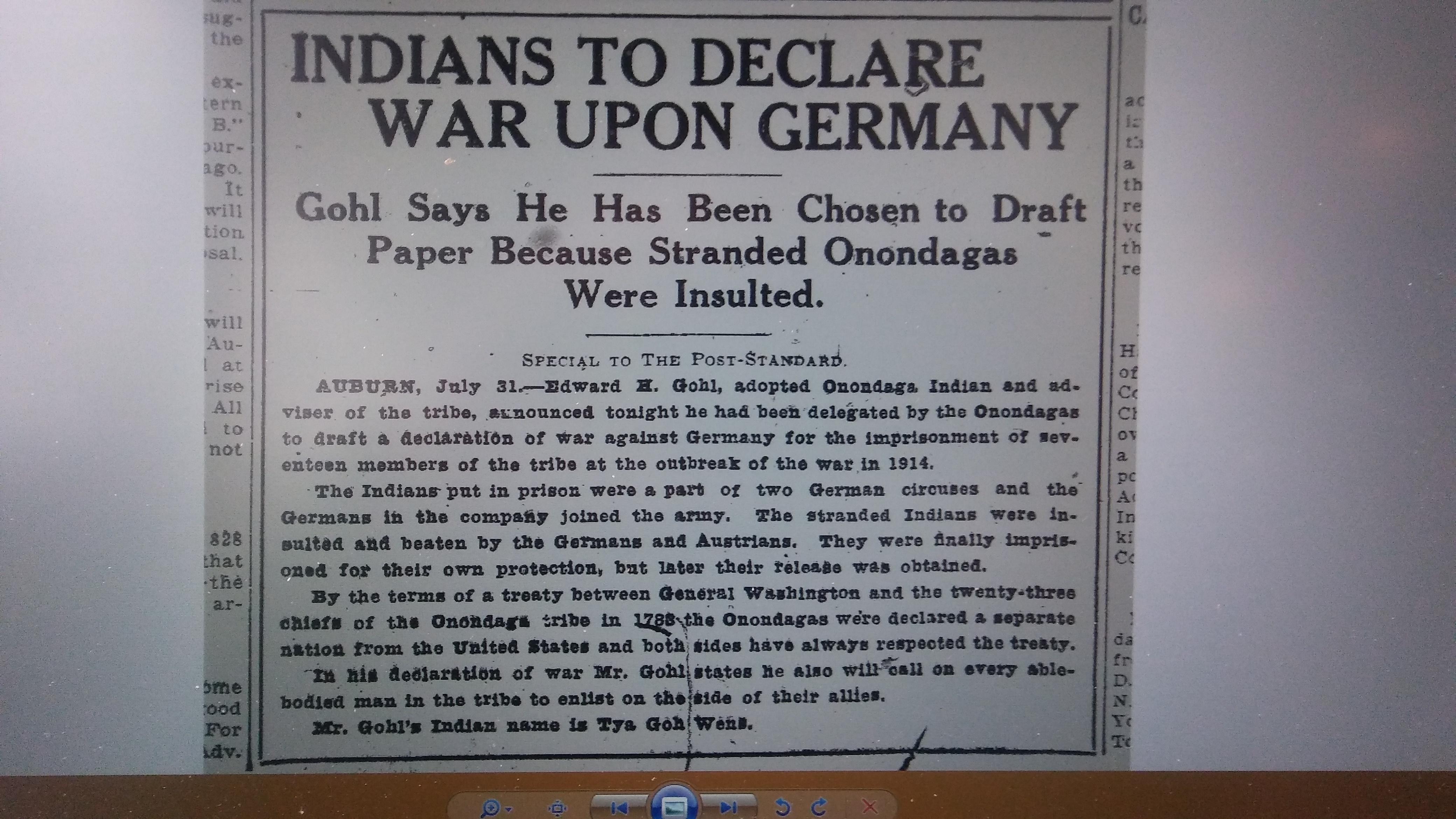

performers, was the Onondaga

performers, was the Onondaga  You can read a profile

You can read a profile

Wherever your school is located, you likely are near a badly biased state historical marker, full of loaded language, displaying common, stereotyped views of native peoples. Your students can research these sites, or the events that took place there, and revise them.

Wherever your school is located, you likely are near a badly biased state historical marker, full of loaded language, displaying common, stereotyped views of native peoples. Your students can research these sites, or the events that took place there, and revise them.

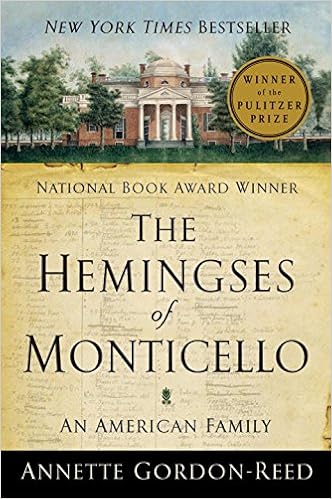

The book won the Pulitzer and the National Book Award, deservedly so in my view. But Lonsberry gave up after attempting to read it, he

The book won the Pulitzer and the National Book Award, deservedly so in my view. But Lonsberry gave up after attempting to read it, he  reconsidering its American history standards. The state became the

reconsidering its American history standards. The state became the