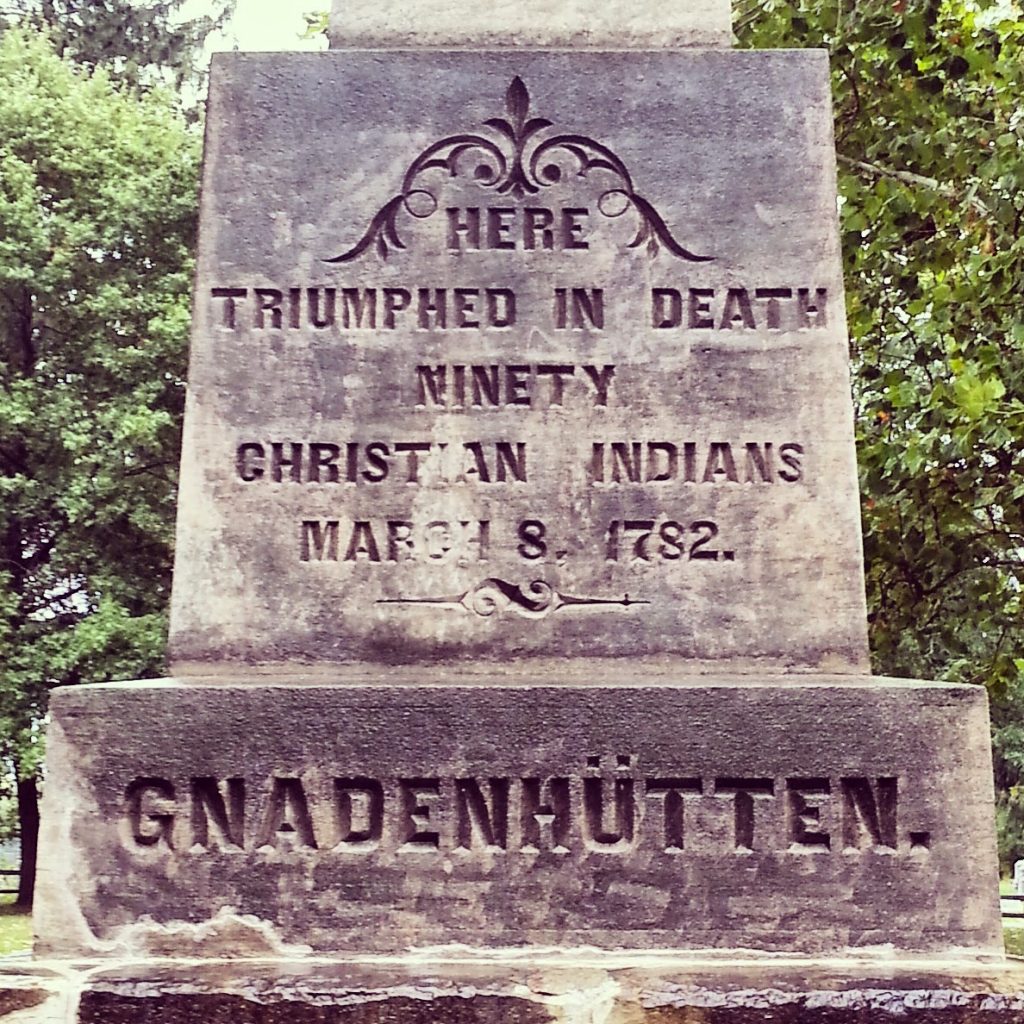

I have been thinking the past two days about the juxtaposition of Native American Heritage Month, something that has been commemorated for almost thirty years now, and the President’s recently proclaimed “National American History and Founders Month.” I am teaching courses this semester on the American Revolution and Native American History. Linking the two stories is easy. Native peoples, after all, did not refer to the American founders as patriots, heroes or freedom fighters. No. They called them “Butchers,” “Killers,” and “Long Knives.” George Washington, the most fatherly of the founders, native peoples called “Town Destroyer,” and they worried that his countrymen would exterminate them. Words and deeds. The American patriots gave native peoples reason to fear for their lives, and to worry about genocide.

Whichever West Wing flunky who wrote the President’s stupid proclamation ignored all of this, and claimed aloud that in 1776, “our Founders gathered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, at Independence Hall to sign the Declaration of Independence, enshrining in the heart of every American a bedrock principle that all men are ‘endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights.'” Indeed, he or she claimed that “the United States will always remain steadfast in our dedication to promoting liberty and justice over the evil forces of oppression and indignity.”

“During National American History and Founders Month,” the President’s Proclaimer proclaimed, “we celebrate the vibrant American spirit that drives our Nation to remarkable heights.” American patriots and heroes, the proclamation continues, “have always been guided by the belief that America must shine brightly out into the world,” and that “this conviction has been at the forefront of the American experiment since our founding.”

It is impossible for me to disagree with the claim “that our democracy’s survival is dependent upon a well-informed electorate,” though that probably means something very different to me than it does to the President’s supporters, but the rest of that is patriotic nonsense. Nevertheless, onward we must go. “To continue safeguarding our freedom,”

we must develop a deeper understanding of our American story. Studying our country’s founding documents and exploring our unique history — both the achievements and challenges — is indispensable to the future success of our great Nation. For more than two centuries, the American experiment in self-government has been the antithesis to tyranny, and our Constitution has secured the blessings of liberty. From the triumphs of war to the victories of the Civil Rights Movement to placing the first ever man on the moon 50 years ago, our Nation has time and again exhibited an unparalleled ability to achieve extraordinary feats. To continue to advance liberty and prosperity, we must ensure the next generation of leaders is steeped in the proud history of our country.

Of course I have read many of these documents. And it no longer surprises me that I hear similar rhetoric about the founders from both sides of the political spectrum. Progress. Striving. Constantly moving closer to the ideals enshrined in the nation’s founding documents. That is what we are told, what we are all supposed to believe. It is as if the Founders set a standard that we unworthy heirs will find just around the next bend, if only we continue pushing on. We are not perfect, we are told, and there have been a few bumps in the road. The trend is upward, however, always getting better, always becoming a bit more perfect. We are Whigs and at times we sound pathetic.

And here’s the thing. There may have been a time when I believed this, but I do not believe it anymore. I have traveled. People who have not experienced our Revolution live in societies that celebrate individual freedom, and that are at least as equally free and just as the United States.

Let’s be honest, America. We have been at this for two hundred and fifty years. The Semiquincentennial of the Declaration of Independence is only seven years away. And if after twelve score years and ten we have yet to attain these ideals, isn’t it possible, and even likely, that we never really embraced them at all? You can admit that, can’t you? These truths, they’re not so transparently self-evident as they may once have seemed after all. Is it possible, and even likely, that this country is racist and rotten at its core? The sins we forget can never be forgiven.

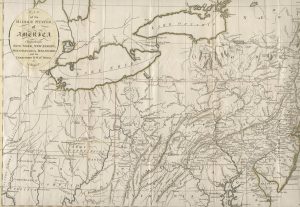

I grew up on land seized from native peoples along the California Coast before the United States, through war, diplomacy, and armed robbery, stole it from Mexico. I live now on land taken through fraudulent transactions by the state of New York from the Haudenosaunee, the People of the Iroquois Longhouse. I look around me and I see a nation fattened on slavery and racism, exploitation and greed, dispossession and violence. Despite the slaughter of 600,000 in the Civil War the nation has yet to do penance for its original sin. A majority of white people still fight to uphold structures of white supremacy, still support efforts to deprive people of color of their right to vote, still support a President who cages thousands of children far from their parents. And that President wastes no opportunity

to rub the noses of native peoples in the fact that what was once theirs belongs to them no longer. With untold numbers of indigenous women and girls missing or murdered, with indigenous lands opened to corporate exploitation and degradation, with indigenous sovereignty and nationhood ignored, and at times with their very existence erased and denied, the President will take that commemoration of Native American Heritage Month, too. What was yours is ours, and if you challenge us you will be destroyed. With his actions, every single day, he screams at peoples of color, “Get the hell out” or “Shut Up” or “disappear.”

That is the America I see. So why do I not leave? Why not find someplace better if it is so miserable here. I have had people ask me that question, but it really was more of an accusation: If I really believe this, after all, how can I possibly teach American history without poisoning young minds?

Tell me where I am wrong, I might say. This is home.

Many, many years ago, I saw a concert by Midnight Oil, one of my all-time favorite bands. I’ve seen them three or four times over the years. Peter Garrett, the band’s lead singer, said once during a break between songs that he would never leave his native Australia until he made it as great as it could be. I think I feel the same way, but I no longer look to the Revolution for the ideals I want to see realized. The founders left me little to celebrate, other than a flawed framework for government that has endured for more than two centuries, despite the fact that nobody in the President’s administration seems to know what it says. For millions of people, the American Revolution unleashed a force that has done far more evil than good. Perhaps someday we will live in a society where all people are truly equal. Perhaps, and on the other hand, along side our proclamations of liberty and justice for all, our racism and our violence, and our exploitation, erasure, and injustice, we are closer to the Founders, warts and all, than we care to admit.

Wherever your school is located, you likely are near a badly biased state historical marker, full of loaded language, displaying common, stereotyped views of native peoples. Your students can research these sites, or the events that took place there, and revise them.

Wherever your school is located, you likely are near a badly biased state historical marker, full of loaded language, displaying common, stereotyped views of native peoples. Your students can research these sites, or the events that took place there, and revise them.