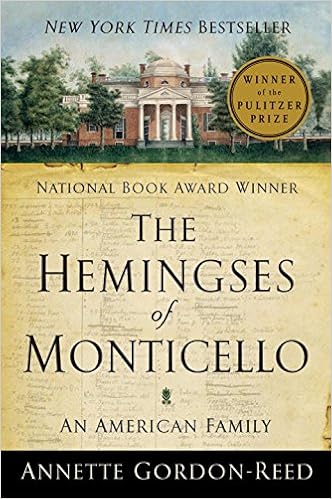

There is a guy named Bob Lonsberry who has hosted a local right-wing radio show here in Rochester for many years. I have mentioned him before on this blog in response to his tweets some months back about Columbus Day. Lonsberry, who about a decade and a half ago was suspended from his job for referring to the city’s African-American mayor as “a monkey,” and who whole-heartedly endorsed the Clown Prince of Mar-A-Lago’s characterization of those parts of the world where people aren’t white as “shitholes,” recently tried to read Annette Gordon-Reed’s The Hemingses of Monticello.  The book won the Pulitzer and the National Book Award, deservedly so in my view. But Lonsberry gave up after attempting to read it, he tweeted, because “the America hatred was just too much. The next generation of historians will probably have to spend most of their careers scrubbing the bias of this generation of historians.”

The book won the Pulitzer and the National Book Award, deservedly so in my view. But Lonsberry gave up after attempting to read it, he tweeted, because “the America hatred was just too much. The next generation of historians will probably have to spend most of their careers scrubbing the bias of this generation of historians.”

My purpose here is not to beat up on Lonsberry, but on the type of thinking he expressed in this tweet. It is a style of reactionary thought with which historians commonly have to contend. We always have and, I suspect, we always will. We had better prepare our students for engaging in this debate.

When I began my teaching career almost a quarter-century ago in Montana, I waded into the controversy over the National History Standards released by UCLA’s National Center for History in the Schools. I had seen Lynne Cheney’s op-ed in The Wall Street Journal proclaiming “The End of History,” and, for reasons I cannot entirely explain, I somehow stumbled across an episode of Rush Limbaugh’s television program (Yeah, he had one) where he sat at his desk tearing pages out of a US history textbook. That, he said, was what liberal college professors were doing to American history.

I ordered a copy of the Standards, read them, and realized quite quickly that the National History Standards did nothing more than bring together a list of subjects that its creators felt students ought to know about the American past. It brought together what historians of the United States had been talking about and writing about for a generation. What lunatics like Limbaugh and ideologues like Cheney denounced as “politically correct” was, in my view, a more historically accurate recasting of American history that wrestled with the complexity of the nation’s past. And, yes, that included wrestling with some of the darkness in the historical record. Students ought to understand slavery, in all its complexity, and they ought to know that the growth and expansion of the United States came at the expense of millions of native peoples who succumbed to epidemic disease, were dispossessed, or destroyed in war.

So I wrote an op-ed in the Billings Gazette. It received some applause, and made for me some friends, but I also got plenty of really ugly hate mail. For there has always been a tension when it comes to teaching American history. For some, history ought to form the foundation of American civic education, and in that sense its cardinal purpose is to instill in students a love of country and patriotism. Casting a critical gaze at the United States, in this view, undercuts that goal. At another level, however, history is an academic discipline, the study of continuity and change, measured across time and space, in peoples, institutions and cultures. Civics vs. the imperatives of the discipline of history. Historians ask questions about the past and conduct research and collect the evidence necessary to answer these questions. Historians ask questions about all sorts of things, and almost any document or artifact can become, in this way, a historical source, even the tweets of a right-wing radio talk show host. Sometimes these questions force us historians to look evil in the face, to stare into the darkness, and to ask, “Why?” And that can be an unsettling question.

I have taught for a long time. Because I teach early American history and Native American history, I end up telling some pretty horrifying stories to my students. In my early American courses, I talk about slavery, an institution which enriched white people and which simply could not have existed without the pervasive and systematic use of violence. To explain the sinister ways that slavery corrupted everything it touched, how the cancer that was this institution bored its way into the dark heart of this continent, I talk about Jefferson, about how this great intellect, when it came to slavery, spent his time wondering aloud about the odor of Africans, their sexual ardor, the location of their color in their skin. Slavery twisted and corrupted him. And I tell the students, because I have to, that the author of the “Declaration of Independence,” who believed that “all men were created equal,” owned his in-laws and had a sexual relationship with his slave. That Jefferson owned and exploited Hemings was not news to historians–the evidence was out there. But Annette Gordon-Reed in her first book proved that case beyond reasonable doubt, and in her second, the book that Bob Lonsberry thought was filled with “America hatred,” she explained, among other things, why we should care.

Look, when I tell my students these stories or, better, when they read them on their own in an assignment or as part of their research, they are disturbed by the viciousness and the violence they uncover. But they tell me every single semester that they are appalled that these stories were hidden from them by their high school teachers. They feel like they were cheated or misled. High school teachers: if you lie to your students, or feed them patriotic propaganda, and they will remember you and judge you harshly.

The kind of sentiment expressed by Bob Lonsberry—we who study the past have seen it before. It is a standard conservative critique, boiled down to a few characters, of the entire historical enterprise. But it is pernicious and racist, and we should work harder than we do now to counter it.

In 2009 I left Geneseo briefly to teach at the University of Houston. I arrived at the time the Texas state education agency was  reconsidering its American history standards. The state became the butt of jokes for a proposed set of standards that white-washed American history, diminished the cruelty of slavery, and mentioned the state’s complicated history with its native peoples not at all. There were other problems, too numerous to mention here. I organized a discussion of the new standards. My colleagues in the history department were extraordinarily supportive, as were the school of education at UH and the director of the University’s Honors College. One of the proponents of the new social studies framework had said on television that “a bad day in the United States is better than a good day anywhere else,” and that history education ought to reflect that. It should convey to students the success of the American experiment. I invited the conservative members of the education commission to come to UH and participate. I told them that they should have their voices heard. They had been in the past quick to denounce what they saw as “politically correct history,” so perhaps they would be willing to make their case. But they would not do it. They made excuses, but I did not believe them. They were, quite simply, afraid to engage in an honest debate.

reconsidering its American history standards. The state became the butt of jokes for a proposed set of standards that white-washed American history, diminished the cruelty of slavery, and mentioned the state’s complicated history with its native peoples not at all. There were other problems, too numerous to mention here. I organized a discussion of the new standards. My colleagues in the history department were extraordinarily supportive, as were the school of education at UH and the director of the University’s Honors College. One of the proponents of the new social studies framework had said on television that “a bad day in the United States is better than a good day anywhere else,” and that history education ought to reflect that. It should convey to students the success of the American experiment. I invited the conservative members of the education commission to come to UH and participate. I told them that they should have their voices heard. They had been in the past quick to denounce what they saw as “politically correct history,” so perhaps they would be willing to make their case. But they would not do it. They made excuses, but I did not believe them. They were, quite simply, afraid to engage in an honest debate.

And that’s the thing that bothers me so much. You do not have to like what you read. You can dislike a book because you do not like the author’s style, or because it does not interest you. All of that is fine. But if you are going to dismiss a work of scholarship because it is “politically correct” or because it is “anti-American” or because it manifests too much “America-hating,” then make your case. Come up with some evidence. Engage in a dialogue. Construct and argument. It is not unreasonable to ask those in the public eye to explain their reasoning, to cite the evidence that leads them to believe what they believe. It is what intellectually mature people do. I realize that is a sort of behavior is not modeled much these days. But I have not lost hope. When Lonsberry dismissed The Hemingses of Monticello for its “America hating” I tweeted back at him, asking him to cite one example of the problem he identified, one factually incorrect statement or claim not supported by evidence in that book. He did not reply, and I realize he might be a busy guy. Still, to dismiss a book because you think it is politically correct and to not provide evidence is, to put it bluntly, chickenshit. It is an intellectually dishonest and morally bankrupt way to suggest that you do not think American children should learn about people of color and that you do not want to hear about the horrors of the past.

I was really struck by your comment about students feeling that they have been cheated by past teachers who gave them a whitewashed version of history. I teach American Indian Law, and I often hear the same reaction. Sometimes students even feel embarrassed (“I thought I was an educated person — how could I not know this?!”). Students are amazed by the Johnson v. McIntosh case when they read it in their Property casebook, and then ask when it was overturned — because surely a doctrine explicitly grounded in religious and racial prejudice cannot possibly still be part of American law. It falls to their professors to burst their bubble. This IS our history, as much as some like to hide or deny it, and it continues to shape lives and law today.

Thanks for your reply, Allison. I like your work a lot. It is interesting how consistently students respond in this manner. I have started turning the question around: Why is it that you are taught so much stuff that is wrong? I live in Western New York. I can walk from here to the current path of the Erie Canal in about five minutes. My campus sits on ground obtained from the Senecas at the 1797 Big Tree treaty. We do not talk enough, in my view, about how New York became the empire state through a systematic program of Indian dispossession. Students need to understand that Native Americans’ losses were white Americans’ gains, and that is fundamental to the American experience. I agree with you entirely.