It has been many years since I last taught the history of the Iroquois, even though nearly all of my research the past ten years has been focused on them. During the Obama years, I offered this course every fourth semester or so but, more recently, I moved in other directions because there were so many other demands on my teaching time. That is what I told myself. The truth is that I find this an immensely challenging course to teach. It is directed towards juniors and seniors, but few of them will have had any previous exposure to Haudenosaunee history. Upper-division courses in Geneseo’s History Department tend to be more narrowly focused, but this course covers five hundred years of history. It is a paradox, a challenge, and frankly it is intimidating to teach. There is loads of bad information about the Haudenosaunee. I want to make sure that what I expose the students to is of value. I offer them little more than a sampling of a rich, diverse, and complicated history, and after a long time away from teaching this course, I am eager once again to face the challenges it presents. I would love to hear your thoughts. I am sure I am not the only history professor who feels daunted by the gravity of the subject they teach.

History 465 Iroquois History from Prehistory to Present Spring 2024

Instructor: Michael Oberg

Meetings, MW, 10:30-12:10, Bailey 246

Phone:245-5730

Office: MW 12:30-1:30, Doty 208

Email: Oberg@geneseo.edu

Required Readings:

Roger Carpenter, The Renewed, the Destroyed, and the Remade, (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2004).

Laurence M. Hauptman, Conspiracy of Interests: Iroquois Dispossession and the Rise of New York State, (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1999.

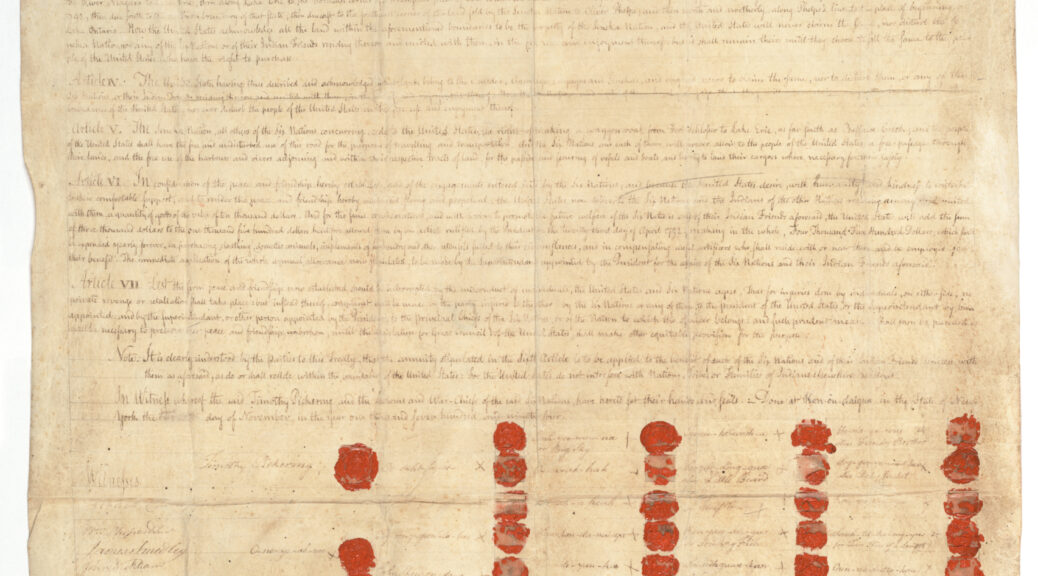

Michael Leroy Oberg, Peacemakers: The Iroquois, the United States, and the Treaty of Canandaigua, 1794, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015).

David L. Preston, The Texture of Contact: European and Indian Settler Communities on the Frontiers of Iroquoia, 1667-1783, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009)

Audra Simpson, Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States, (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014).

Readings online and on Brightspace

Course Description:

In this course we will cover the history of the native peoples who formed the Iroquois League and Confederacy, from the time of their first contact with Europeans through the present-day controversies that occur across the state. We will look at the formation of the League, the consequences of Iroquois involvement in the European Wars of Empire, and the rapid dispossession of the Iroquois in the decades that followed the American Revolution. We will look at the application of various government policies in the United States and Canada to the Iroquois, and how the Iroquois have reacted to and adapted to these changes. Throughout, we will keep in mind the different histories of the constituent Iroquois communities that occupy present-day New York, Wisconsin, Oklahoma, and Canada.

Your grade for the course will be based on the following assignments:

- Journals: On seven occasions during the semester I will read your journals. I want you to think about what you are reading and write about that experience. You will submit your journals on Brightspace. You should plan on writing a minimum of 300 words a week. DO NOT SUMMARIZE OUR CLASS DISCUSSIONS. DO NOT SUMMARIZE THE READINGS. I hope you will take this assignment as an opportunity to reflect upon what you are reading in class and to discuss the things you wish that we had a chance to discuss in class, or to say what you wanted to say during one of our class meetings. Use your journal as an opportunity to reflect on the contents of one of the documents you have read. Show me that you are thinking about the material we cover in our readings and in the classroom. Discuss the challenges you are confronting as you work on your research paper. Write each entry in the spirit of an essay, with a thesis and evidence to support your reasoning. The due dates—always on a Friday, always on Brightspace—are listed below

- Research Paper: I expect all students enrolled in this course to complete a research paper of approximately 15-20 pages in length, based upon primary source research and a thorough grounding in the secondary source literature. I urge you to visit with me regularly during office hours as the semester progresses, to ensure that your research project develops as it should. You will work on your paper in stages, completing preliminary assignments along the way towards the completion of a final draft. Those components are as follows:

a). Question and Sources: In this one-page paper, you will state the question you hope to investigate for your research paper. You should list the sources you think you will need to answer that question in a bibliography that follows the format of the Turabian Manual. Due on Brightspace February 5th

b). Topic Statement: A more-refined and specific statement of the topic you would like to research and the sources you will need to answer your specific historical question. Due on Brightspace, February 19th.

c). Thesis statement and outline. Due on Brightspace, April 1st.

d). Hard Copy of Draft to be turned in at end of class on April 22nd.

e). Hard Copy of Final Paper, due on May 8th at end of class period.

I will write extensive comments on your written work. I will ask you challenging questions, offer what I hope you will view as constructive criticism, and encourage you to push yourself as a writer and a thinker. But I will not give you grades, in the traditional sense, on this work. I want you to benefit from this course. On the date of our first meeting, we will discuss the standards for the class. You and I will work together to arrive at a set of expectations for the sort of work that will earn a specific grade. In your final journal, and in individual meetings scheduled during Finals Week, we will discuss how well you think you did in meeting the agreed upon standards, and what your grade for the course ought to be. A proposed grading framework can be found, below.

- Participation: I assign a large quantity of reading. I expect each of you to participate regularly in our class discussions. To receive a strong grade in this course, you must speak up in class. The discussion questions, below, are intended to serve as a guide to help you with the reading assignments. If you are able to answer these questions, you should be able to participate without much difficulty. Participation is much, much more than attendance.

A Note on Phones: I ask that all cellphones be stored during the entirety of our class meeting. If you expect an important call that just cannot wait, please inform me before class. Otherwise, I expect you to refrain from using your cellphone and I expect you to keep it out of sight. Please be present in mind and body. Much of the reading for this course will be online or available on Brightspace. You will need to bring your laptop to class, but I expect you to use it for class-related work only. Students who violate these policies will be asked to leave the class.

Lecture/Discussion Schedule

22 January Introduction to the Course: The Importance of the Iroquois

Reading: Carpenter, Renewed, xi-xxii; Preston, Texture, Acknowledgments, and Introduction; Oberg, Peacemakers, Acknowledgments and Introduction; Hauptman, Conspiracy, Preface; Simpson, Mohawk, Acknowledgments and Chapter One. Visit some of the websites of Iroquois communities in New York State, such as:

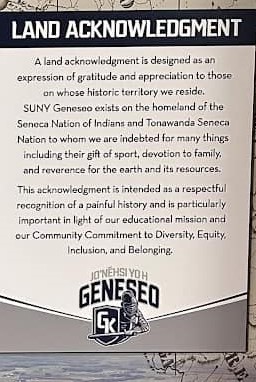

Also worth your time is the web project entitled Chenussio: An Indigenous History of Livingston County. If you know nothing about the history of the Iroquois, the “Overview of Seneca History” might be useful (the sections are meant to be opened left to right, beginning on the top row). It focuses only on the Senecas, but the larger themes will be important for you to know. Be sure to click on the Livingston County First Nations Sites on the landing page, to learn a bit more about the area in which you are studying.

Furthermore, READ THE SYLLABUS CLOSELY. MAKE NOTE OF DUE DATES FOR EACH PROJECT.

For Discussion: What do you know to be true about the Iroquois in New York, Canada, Wisconsin, and Oklahoma? What do you learn about the scholars you will be reading this semester from reading the front matter in their books? What are your thoughts about the grading agreement at the back end of the syllabus? Do you feel it is fair and, if not, in what ways might we work together to improve it?

24 January Tales of Creation

Reading: Carpenter, Renewed, Chapter 1; Kuhn and Sempowski, “A New Approach to Dating the League of the Iroquois,” American Antiquity, 66, No. 2, (April 2001), 301-314; Christopher Vecsey, “The Story and Structure of the Iroquois Confederacy,” Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 54 (Spring 1986), 79-106; John Arthur Gibson, Concerning the League: The Iroquois League Tradition as Dictated in Onondaga, ed. And trans, Hani Woodbury, in collaboration with Reg Henry and HarryWebster. Algonquian and Iroquoian Linguistics. Memoir No. 9, (Winnipeg, 1992). (All on Brightspace).

For Discussion: What are the key elements, concepts, and values that emerge from the creation stories of the Iroquois? What are the most important themes in the Deganawidah Epic? How did the League form and how does that information help us understand the Iroquois League?

29 January The League and Early European Contacts

Reading: Carpenter, Renewed, Chapter 2; David Hackett Fischer, Champlain’s Dream: The European Founding of North America, (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2008), 317-342; Harmen Meyndertsz van den Bogaert, “A Journey into Mohawk and Oneida Country, 1634-1635,” in In Mohawk Country: Early Narratives about a Native People, eds. Dean R. Snow, Charles T. Gehring, and William A. Starna, (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1996) (on Brightspace)

For Discussion: How did Iroquois apply the lessons and values of the Deganawidah Epic in their relations with other peoples? How would you characterize exchange and trade between Iroquois people and the early European settlers? Was it primarily an economic relationship, or something else? What thesis is Carpenter arguing?

31 January The Destruction of Huronia

Reading:Carpenter, Renewed, Chapters 3-4, 8-9. (You should skim Chapters 5-7 closely enough that you understand how the French in general, and the Jesuits specifically, altered the Wendat thought world. We will come back to Chapters 5-7 in detail later).

For Discussion: What significance do we attach to the Iroquois warfare that took place between 1634 and 1649?

2 February Journal 1 Due on Brightspace

5 February The Mourning Wars

Reading: Daniel K. Richter, “War and Culture: The Iroquois Experience,” WMQ 40 (October 1983), 528-559; Jose António Brandǎo, “Iroquois Expansion in the Seventeenth Century: A Review of Causes,” Native American Studies, 15 (2001), 7-18 (Brightspace).

Question and Sources Due! On Brightspace

For Discussion: In what ways do Richter and Brandǎo differ in their interpretation of Haudenosaunee warfare in the second half of the seventeenth-century?

7 February The Covenant Chain

Reading: Jon Parmenter, “After the Mourning Wars: The Iroquois as Allies in Colonial North American Campaigns, 1676-1760,” William and Mary Quarterly, 64 (January 2007), 39-76

For Discussion: How did the Covenant Chain alliance benefit the Five Nations? How did it benefit the English? Did it benefit certain English more than others? What was the nature of this alliance? How did it work? How important is the Covenant Chain for understanding the history of European colonialism in 17th Century America?

12 February Christians and Iroquois

Reading: Carpenter, Renewed, Chapters 5-7; Preston, Texture of Contact, Chapter 1; The Jesuit Relations: Natives and Missionaries in Seventeenth-Century North America, ed. Allan Greer, (Boston: Bedford, 2000), Chapters 6-7.

For Discussion: What did it mean to the Jesuit Fathers for one to be a Christian? How did the Jesuit Fathers view the religion of the Five Nations and the Wendats? Be prepared to discuss the nature of Iroquois Christianity.

14 February To the “Grand Settlement” of 1701

Reading: Brandao, J. A. and William A. Starna, “The Treaties of 1701: A Triumph of Iroquois Diplomacy,” Ethnohistory, 43 (Spring 1996), 209-244.

For Discussion: What was the significance of the treaties of 1701?

16 February Journal 2 Due on Brightspace

19 February The Haudenosaunee and the English Empire in America

Reading: Oberg, Peacemakers, Chapter 1; Parmenter, “’L’Arbre de Paix’: Eighteenth-Century Franco-Iroquois Relations,” French Colonial History, 4 (2003), 63-80.

For Discussion: Are the eighteenth-century Iroquois best characterized as subjects of the English empire or as allies of the Empire? How does one best characterize the functioning of the Covenant Chain? How would you characterize the Haudenosaunee relationship with New France?

Topic Statement Due!

21 February Brother Onas

Reading: Preston, Texture of Contact, Chapter 3

Kurt A. Jordan, “Seneca Iroquois Settlement Pattern, Community Structure, and Housing, 1677-1779,” Northeast Anthropology, 67 (2004), 23-64.

For Discussion: Describe the Importance of Pennsylvania to the Iroquois.

26 February Economic Life in Iroquoia in the Middle of the Eighteenth Century

Reading: Preston, Texture of Contact, Chapter 2

For discussion: Last time we briefly discussed Kurt Jordan’s important archaeological work on Seneca settlement patterns. Based on your reading of Preston, how would you characterize the relationship of Iroquois peoples with the larger colonial economy? Are they dependent on the colonists? Did they manage to preserve a degree of autonomy in their relations with outsiders? How does one characterize this “frontier”?

28 February The Albany Congress and Mounting Tensions in Pennsylvania

Reading: Preston, Texture of Contact, Chapter 4; Levy, “Exemplars of Taking Liberties.”

For Discussion: Haudenosaunee people emphasize the importance of the Covenant Chain. Are they correct to do so? What were the sources of conflict for Iroquois peoples in the middle of the eighteenth century?

1 March Journal 3 Due on Brightspace

4 March The Great War for Empire

Reading: Preston, Texture of Contact, Chapters 5-6

For Discussion: What were the causes of Great War and how did the conflict between France and Great Britain for control of North America impact Haudenosaunee peoples in the Ohio Country, Pennsylvania, and the western parts of today’s New York?

6 March The Haudenosaunee and the American Revolution

Reading: Preston, Texture of Contact, Epilogue; Oberg, Peacemakers, Ch 2.

For Discussion: To what extent was the American Revolution a civil war for the Six Nations? What factors influenced the reactions of Iroquoian peoples to the outbreak of fighting between American Patriots and British soldiers? In what ways did the Revolution matter to the Iroquois? Was it a significant event? Did it merely continue the assaults on Iroquois lands that began long before the Revolution? In what ways did the Revolution impact the Iroquois?

Spring Break

18 March The Post-Revolutionary Diaspora

Reading: Oberg, Peacemakers, Chapters 3-8 and Appendix.

For Discussion: How did the State of New York and the United States claim and exercise jurisdiction over the Iroquois homeland? How would you characterize federal Indian policy in the years immediately following the American Revolution? How significant an accomplishment was the Treaty of Canandaigua?

20 March New York’s Assault on Iroquois Land

Reading: Oberg, Peacemakers, Chapter 9 and Conclusion; Hauptman, Conspiracy, Introduction, Part One

For Discussion: To what extent was New York engaging in illegal activity when it seized native lands? What was New York’s interest in the dispossession of the Iroquois? What factors made the Iroquois particularly susceptible to attempts to dispossess them? What happened at the treaty council held in 1795? How do you account the willingness of the Oneidas, Onondagas and Cayugas to sign treaties ceding land to the state of New York?

22 March Journal 4 Due on Brightspace

25 March Seneca Land

Reading: Hauptman, Conspiracy, Chapters 7-8; Lewis Henry Morgan, League of the Iroquois, reprint ed., (New York: Citadel Press, 1962), Part II, Chapter III

For Discussion: What was Handsome Lake’s message? Of what elements did it consist of? What changed as a result of Handsome Lake’s teachings? What, to Dennis, is the fundamental importance of the Handsome Lake religion?

27 March Seneca Land, Continued

Reading: Hauptman, Conspiracy, Chapters 9-10

For Discussion: Why did the Senecas agree to sell their land? Describe the nature of the relationship between Quaker missionaries and the Seneca Indians. How did the Senecas make use of the Quakers’ message? What did the Quakers and Senecas hope to achieve through their relationship with the other?

1 April The Iroquois and Indian Removal

Reading: Oberg, Professional Indian: The American Odyssey of Eleazer Williams, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015), Chapter 3, Brightspace.

For Discussion: What force or forces were most responsible for the “removal” of the New York Indians?

Thesis Statement and Outline Due!

3 April The Seneca Revolution of 1848

Reading: Henry Schoolcraft’s Notes on the Iroquois, Chapter One; Documents on the Seneca Revolution.

For Discussion: To what extent was the Seneca Revolution consistent with the new Seneca Nation’s understanding of its earlier treaties with the United States? How significant an expression of Iroquois sovereignty was the new Seneca Nation government? Indeed, what is the meaning of the Seneca Revolution?

5 April Journal 5 Due on Brightspace

8 April Solar Eclipse—No Class.

10 April The Iroquois and the Civil War

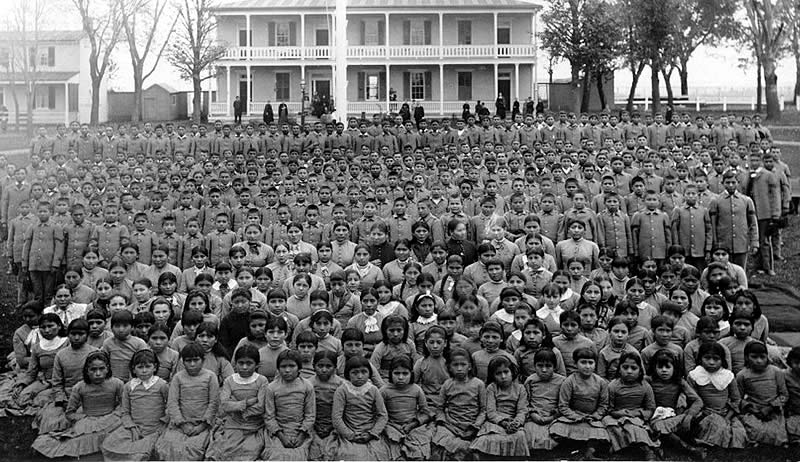

The Thomas School and Carlisle

Reading: Laurence Hauptman, The Iroquois in the Civil War: From Battlefield to Reservation, (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1993), Chapter One; Carlisle Student Records, available here. Under the “Nation” pull-down menu, search for student records from the Senecas, Onondagas, Oneidas, Tuscaroras, Mohawks and Cayugas. Read at least five student files. What can you learn about the Iroquois experience at Carlisle from these records?

For Discussion: The involvement of native peoples in the American Civil War has been an understudied aspect of this important event in American history. How did Iroquois peoples respond to the outbreak of the American Civil War? Was the Civil War actually an event for Haudenosaunee peoples? What impact did it have upon them?

15 April The Legal Status of the Six Nations: Allotment, the Kansas Claims, and the Everett Commission

Reading: New York State Legislature. Assembly Doc. No. 51. Report of the Special Committee to Investigate the Indian Problem of the State of New York, Appointed by the Assembly of 1888, 2 vols. (Albany: Troy Press, 1889) (excerpts); Arthur C. Parker, “The Legal Status of the American Indian;” Everett Commission Report, pp 2-14

For Discussion: Many Haudenosaunee see the Everett Commission Report as a document of great significance. Why?

17 April Citizenship and the State

Reading: Sidney L. Harring, “Red Lilac of the Cayugas: Traditional Indian Law and Culture Conflict in a Witchcraft Trial in Buffalo, New York, 1930,” New York History 73 (1992), 65-94; Indian Citizenship Act (1924); Indian Reorganization Act (1934); Documents on Death Feasts (All on Brightspace).

For Discussion: Who killed Cothilde Marchand, and why should we care? Why did the Iroquois, in general, oppose the Indian Reorganization Act?

19 April Journal 6 Due on Brightspace

22 April Iroquois in the Era of World War II

Reading: http://www.nysl.nysed.gov/scandocs/nativeamerican.htm

At the New York State Library website, look at one of the following documents. All of them relate to issues facing the Haudenosaunee during the Second World War and are influenced by federal debates about the policy of termination, and whether or not the State of New York ought to have criminal and civil jurisdiction over Indian reservations in New York State.

1). Public Hearing had at Salamanca, New York Court Room, City Hall, August 4-5, 1945.

2). Public Hearing had at Thomas Indian School, Cattaraugus Reservation, N.Y., Wednesday, Sept. 8, 1943

3). Hearing Before the Joint Committee on Indian Affairs on Thursday, Jan. 4, 1945 at Ten Eyck Hotel, Albany, N.Y.

For Discussion: Based on your skimming of the above documents, and your close reading of one of them, how would you characterize the challenges facing the Iroquois during the early 1940s?

Hard Copy of Draft Due!

24 April GREAT DAY: No Classes

29 April The Haudenosaunee in the Post-War Era

Reading Laurence Hauptman, “Where the Patridge Drums: Ernest Benedict, Mohawk Intellectual as Activist,” in Seven Generations of Iroquois Leadership, (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2008). We will watch together in class “Lake of Betrayal,” a film about Kinzua Dam and the flooding of the Senecas’ Allegany Reservation.

For Discussion: Based on the three essays I have asked you to read, how would you describe the principal issues facing the Mohawks and Senecas in the post-war era? How would you characterize Seneca and Mohawk responses to the challenges they faced?

1 May The Six Nations and Red Power

Reading: Hauptman, “The Iroquois on the Road to Wounded Knee,” in The Iroquois Struggle for Survival: World War II to Red Power, 1986); “Basic Call to Consciousness;” Film, “Lake of Betrayal.”

For Discussion: What has the era of “Self-Determination” meant to the Six Nations? What significance do you attach to Iroquois efforts to recover their stolen lands?

3 May Journal 7 Due on Brightspace

6 May Haudenosaunee Nationhood

Reading: Simpson, Mohawk, Chapters 2-4

For Discussion: What obstacles to a meaningful nationhood still face the people of the Longhouse?

8 May Final Class Meeting: Indigenous Nationhood in the Future

For Discussion: Finish reading Simpson, Mohawk; Town of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation (2005).

Term Papers Due!

14 May 8:00-11:20. Final Exam Period: Individual Meetings to discuss your final grade.

A Note on the Term Paper:

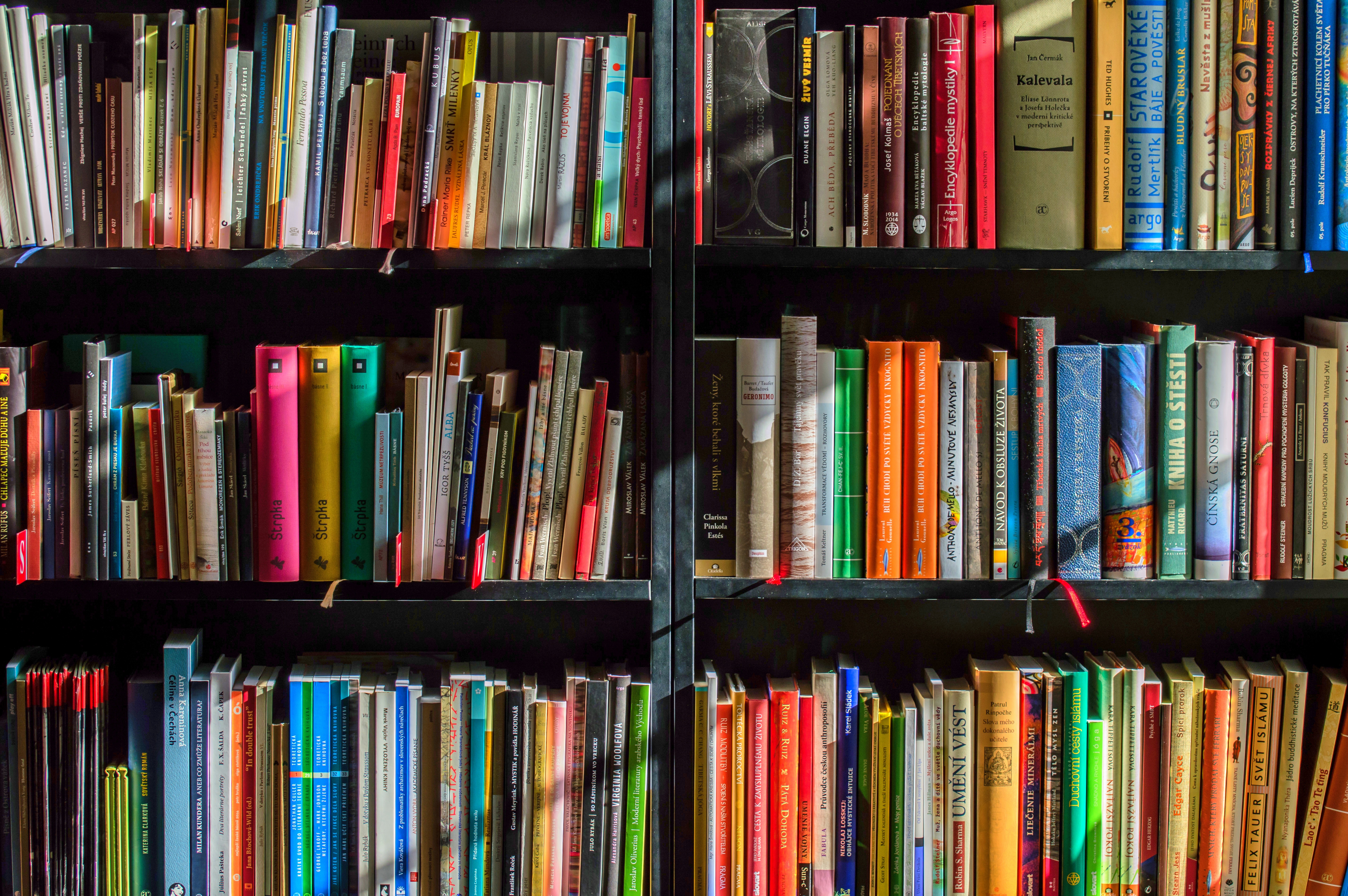

Our humble temporary library contains an extraordinary amount of material for conducting research in Iroquois history. Most importantly, we have a copy of the Iroquois Indians Microfilm Collection, compiled in the 1980s by the Newberry Library in Chicago. This fifty-reel collection includes copies of nearly every important document related to Iroquois relations with outsiders, a vast collection covering the period from the early seventeenth- through to the end of the nineteenth century from libraries throughout North America and Europe. Using the Iroquois Indians Microfilm collection has spared me the necessity of making numerous research trips to Albany, Ottawa, and Buffalo. We subscribe to many of the journals and own many of the books mentioned in the excellent bibliographies included in the back of the Hauptman, Taylor, and Shannon books (Richter’s bibliography is excellent as well, though his book is now a bit dated—he is a great place to start, but you will need to look elsewhere). For those of you interested in the Revolutionary period, we have the entire run of the Papers of the Continental Congress. The library’s Genesee Valley Collection is especially strong on the history of the Senecas, as is the phenomenal range of materials housed at the Rochester Museum and Science Center. The Rush Rhees Library at the University of Rochester has many of the materials that our library does not have. Many papers documenting early relations between the United States and the Six Nations can be found at the “Century of Lawmaking” website at the Library of Congress. Both the New York State Library and the New York State Archives, on their respective websites, have made an intriguing selection of documents readily available to those who cannot travel to Albany to conduct research. Additionally, I have copies of the federal records dealing with the Iroquois through the middle of the nineteenth century. These I will put on reserve should any of you be interested. And with Google Books and the resources placed online by the New York State Archives and New York State Library, an enormous amount of primary source material is readily available to you. Indeed, the most important New York State collections of documents (the Hough Collection, the Whipple Report, and the Everett Report) are all available online. The “Digital Turn” in the Humanities has resulted in large numbers of archival and manuscript collections being placed online. It is easier to do significant research than ever before. But only if you start early, work diligently, and seek help in overcoming the roadblocks you inevitably will face.

If you have no idea what to choose as the topic for your research paper, I encourage you to look at websites like INDIANZ.COM, and use the search feature to look up articles that have appeared in North American newspapers in recent months on Iroquois communities. Consider the individual New York Iroquois communities, or the Oneidas in Wisconsin or the Seneca-Cayugas of Oklahoma. Perhaps you could look into the historical background of some present-day controversies. You can also read through Volume 15 of the Smithsonian Handbook of Americans, located in the reference section of our library. Included are a number of useful articles on the history of the Iroquois League, and of the different Iroquois communities in New York, Canada, Wisconsin and Oklahoma. The listing of primary sources in this old handbook is still quite useful, and reading it can give you a thumbnail sketch of Iroquois history and perhaps focus your attention on something you would like to investigate further. If none of these endeavors pan out, please feel free to read ahead: perhaps some of the readings that we will discuss late in the semester will suggest to you lines of inquiry that would make for a fine paper. I have compiled a 600+ page annotated bibliography on Onondaga Nation history. I have placed a copy of that bibliography on my departmental webpage.

The best advice I can give you about the research paper is to stop by during office hours, email me, or talk to me after class. You probably cannot have too much guidance, and I encourage you to visit with me if you have any concerns about the research paper. If this class goes according to plan, you will produce a research project that we both learn from, and I am more than willing to help you achieve that goal. Do not hesitate to ask for help. AND WHATEVER YOU DO, DO NOT PROCRASTINATE! The most successful students decide upon and begin work on a narrowly focused and well-conceived project early in the semester.

Integrative and Applied Learning Outcomes at SUNY Geneseo: Your research project and journal writing are intended to develop in you the following skills:

- Structured, Intentional, and Authentic Experiences: Integrative and applied learning experiences should include a course syllabus or learning contract between parties and should have hands-on and/or real-world elements.

- Preparation, Orientation, and Training: Integrative and applied learning experiences should include sufficient background and foundational education and should include expectations that are expressed as learning outcomes that structure the experience and ongoing work.

- Monitoring and Continuous Improvement: Integrative and applied learning experiences should include in-experience mechanisms for feedback, course correction, quality monitoring, and evaluation of progress towards the state learning outcomes.

- Structured Reflection: Integrative and applied learning should include opportunities for students to self-assess, analyze, and examine their experience and to evaluate the outcomes. Reflection should demonstrate relevance and should form connections with previous experiences and/or future planning as well as a demonstration of one of Geneseo’s core values: Civic Engagement, Sustainability, Inclusivity, Learning, or Creativity.

- Evaluation: Students must receive appropriate and timely feedback from the project organizer.

Some Potential Term Paper Topics For Those Who Need Suggestions

* The history of a particular Jesuit Mission to a particular Haudenosaunee Nation.

* The dispossession treaties of 1788 or 1795. You cannot do all the treaties well, but you could do a very good paper on one of the individual treaty councils.

* The 1924 Citizenship Act

* The 1934 Indian Reorganization Act

* The Mid-Twentieth Century “Spite Bills” that extended New York’s jurisdiction over the Iroquois.

* Onondaga Death Feast controversies in the 1920s and 1930s.

* Efforts to allot Haudenosaunee land carried out by New York State late in the 19th century

* The Haudenosaunee and the United Nations. You will want to narrow this down, but there is a story to tell here.

* Deskaheh (Levi General) and the League of Nations.

* Haudenosaunee students at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School

* Chenussio in the 17th or 18th century.

* Onondagas and efforts to clean up Onondaga Lake, for a time the most polluted body of water in North America.

* 19th-century agriculture on Haudenosaunee reservations in New York.

* The Buffalo Creek Treaty of 1838. There are a number of things here you might focus on.

* The death of Big Tree early in the 1790s.

* Urban Iroquois: Haudenosaunee people in Buffalo, Rochester, or Syracuse.

* Haudenosaunee circus performers, late 19th, early 20th century.

* The “Indian Village” at the New York State Fair.

* The Everett Report

* The Whipple Report

* The Rise of the Iroquois Nationals Lacrosse Team as an international force.

* Commemorations of important events in Iroquois History in Geneseo, Livingston County, or your hometown.

* None of these appealing? Let’s talk.