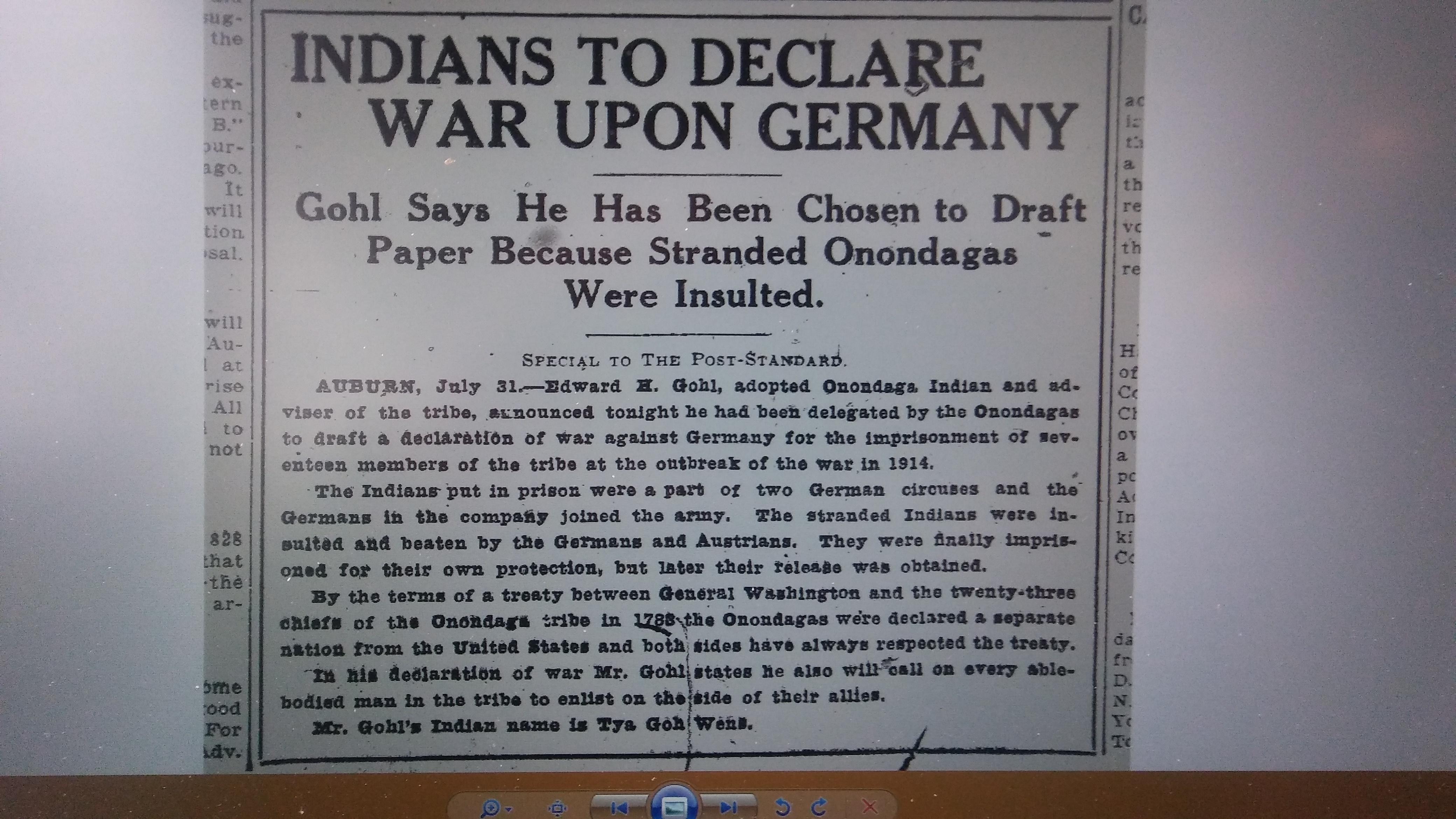

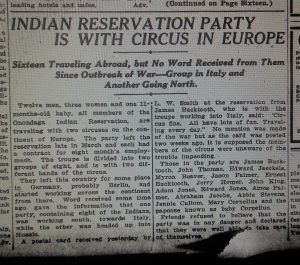

In August of 1918, the following news story appeared in the Syracuse Post-Standard. Under the headline, “Indians to Declare War Upon Germany,” and a smaller title indicating that “Gohl Says He Has Been Chosen to Draft Paper Because Stranded Onondagas Were Insulted” we learn something of an adopted Onondaga, a group of imprisoned circus performers, and inexplicably angry Germans and Austrians.

“Edward M. Gohl, adopted Onondaga Indian and adviser of the tribe, announced tonight he had been delegated by the Onondagas to draft a declaration of war against Germany for the imprisonment of seventeen members at the outbreak of the war in 1914.

The Indians put in prison were a part of two German circuses and the Germans in the company joined the army. The stranded Indians were insulted and beaten by the Germans and Austrians. They were finally imprisoned for their own protection, but later their release was obtained.

By the terms of a treaty between General Washington and the twenty-three chiefs of the Onondaga tribe in 1788 the Onondagas were declared a separate nation from the United States and both sides have always respected the treaty.

In his declaration of war Mr. Gohl states he also will call on every able-bodied man in the tribe to enlist on the side of their allies.

Mr. Gohl’s Indian name is Tya Goh Wens.

There is, to say the least, a lot going on here, more than meets the eye. Though the Onondagas negotiated a treaty in 1788, it was with the State of New York and not George Washington, and there was little in the agreement that was worthy of respect. Gohl shows up frequently in the press as a representative for the Onondagas, though there is much about the relationship that I do not yet understand. And the passive voice: “their release was obtained,” but by whom, how, and when? Documents like these, so suggestive yet so frustrating, I like to give to my students on those rare occasions when I teach my department’s required course in historic research methods, or when I teach a freshman writing seminar that I sometimes call “Life Stories.” Stories like these, it seems to me, open a world of questions, a series of trails to follow that all are utterly enticing.

I’ve been working on my history of Onondaga as a place and a native nation for almost a decade now and I have still a couple of more years of research before I will be able to set pencil to paper and begin my writing process. So many documents, and so much material, I still have to look at. There are still a number of archives to visit and a large amount of evidence to collect and consider. And so many of these small pieces of information, these bits of stories, raise questions that demand answers. They tug at me. They present alluring side trails that seem so worthy of investigation. Down these by-ways and detours and secret paths we can find the human stories that, when they are told well, bring history to life. Even when the answers are not certain, and the conclusions drawn are far from definitive.

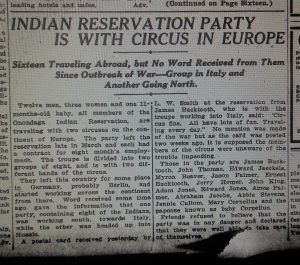

In the summer of 1914, sixteen Indians from the Onondaga Reservation just south of Syracuse New York made their way to Europe to perform with a German circus company. After they arrived in Berlin, they split into two groups. One headed eastward toward Russia, the other south towards Italy. Nobody at Onondaga had heard from them in several weeks the Post-Standard reported in August of 1914, and their friends at home were worried. It was August, and the Great War had begun.

I have much still to learn about these sixteen Onondagas and their experiences overseas. I do not know as of yet the name of this particular circus, how these Onondagas were recruited to join it, and what their lives were like once they returned home. I do not know how the sixteen Onondagas in 1914 became seventeen three years later. I know little about what they saw in Europe, or how their journeys affected them. I do not know where they performed, what they did, and what those audiences expected from them. I know that not all historical questions have answers. We who write about the past are often left with only our ability to imagine, and that is just fine.

I know the names of the sixteen Indians from Onondaga, of course. It seems likely to me that Jerry Homer, one of the Onondaga  performers, was the Onondaga Jeremiah Homer who, ten years before, had arrived at the Carlisle Indian School. He was one of five Homer children to attend Carlisle. According to the school’s records, he was ten years old when he arrived. He was a tiny, tiny kid, just three-and-a quarter feet tall. He weighed only fifty pounds. He may have arrived malnourished, though his older sister, who died young, was also reported to have had a very slight build.

performers, was the Onondaga Jeremiah Homer who, ten years before, had arrived at the Carlisle Indian School. He was one of five Homer children to attend Carlisle. According to the school’s records, he was ten years old when he arrived. He was a tiny, tiny kid, just three-and-a quarter feet tall. He weighed only fifty pounds. He may have arrived malnourished, though his older sister, who died young, was also reported to have had a very slight build.

The Carlisle School sent questionnaires to former students. They liked to know what their alums had done with their lives. The students’ answers allow small glimpses into the lives of ordinary native peoples who lived late in the nineteenth and early in the twentieth centuries. Jeremiah Homer did not say much in his response. In 1911 he reported that he was living on the Onondaga Nation territory and that he wished that the school would send him copies of the Carlisle Arrow, the school’s newspaper. He indicated as well that he was now married to Mary Cornelius, an Oneida woman whose family lived at Onondaga.

Mary Cornelius did not attend Carlisle, but she was enrolled for two years at the state’s Thomas Indian School from 1907 until 1909. One of the sixteen Indians from Onondaga who went to Europe, and who was later imprisoned, was Mary Cornelius. Jerry met Mary, I would guess, sometime after they returned to Onondaga from their time at boarding school. Both were home by 1909. They were married by 1911, Jerry indicated, and the otherwise unnamed “Baby Cornelius” mentioned in the story must have been their child.

Mary Cornelius became an important figure in the twentieth-century history of the Oneidas. You can read a profile here. Jerry Homer is tougher to figure out. Mary and Jerry do not appear to have lived together upon their return to the reservation, and Jerry or Jeremiah Homer disappears from the reservation census records by 1920. I wish I knew more about what happened to him, but at this point, that is as far as the trail leads. By-ways and detours. Some times you wander down a path, only to realize the need to return to the main trail. The resources to answer the questions I have about this family, about their experience in Europe–they are not at my disposal right now. I will have to travel, hit the archives once again, to finish telling this small story.

You can read a profile here. Jerry Homer is tougher to figure out. Mary and Jerry do not appear to have lived together upon their return to the reservation, and Jerry or Jeremiah Homer disappears from the reservation census records by 1920. I wish I knew more about what happened to him, but at this point, that is as far as the trail leads. By-ways and detours. Some times you wander down a path, only to realize the need to return to the main trail. The resources to answer the questions I have about this family, about their experience in Europe–they are not at my disposal right now. I will have to travel, hit the archives once again, to finish telling this small story.

I am confident that I will be able to find the evidence that will help me flesh out these stories. Perhaps some of you reading this now know more than I and, if so, I hope you will share with me what you know. If the evidence exists, I will find it. It might take time. Many paths I follow–that any historian follows–invariably lead to dead ends.

So why bother? Is there something in this, as one of my professors used to ask, of more than mere antiquarian interest? I am writing a book looking at one small piece of land, and the people who lived there, over a span of more than six centuries. Given the vastness of that story, why give so much time and thought to two individuals about whom it is possible, at the end of the day, to know very little?

It is fun, for one thing. It is hard sometimes for my students to appreciate this. They have a lot to carry, and we compel them when we assign research projects to come up with something meaningful to say in a short, fifteen-week semester. They do not have the time to wander down back alleys and by-ways in search of interesting stories. I think that is something about which we need to be more aware. I have no deadline on this project. A lot of us do the work we do, which so often we do alone and in isolation, because it is so immensely satisfying. we pour hours into our projects, into our attempts to find answers to the questions that bother us. Our work does not always result in publication. But the work, for many of us, is its own reward.

But more than that, telling the stories of people like Jerry/Jeremiah Homer and Mary Cornelius allows us to paint a more accurate picture of the communities about which we write. Being Onondaga, or being an Oneida living at Onondaga, or being Native American generally, meant so many different things to so many different people. White lawmakers in New York State, federal officials, Christian missionaries, local law enforcement–they all had their own views of who Indians were and what they might become. And native peoples themselves always defied and complicated these necessarily limited understandings and racist stereotypes. Writing the history of a place like Onondaga, then, means looking not only at the policy makers and the nation’s faction-tattered leaders but the lacrosse players who tested themselves against Ivy League teams, or the members of the “American Indian Concert Band,” formerly known as the “Onondaga Indian Concert Band,” which was led by David Russell Hill and claimed to be the “only professional Indian band known to both hemispheres”; or the bricklayer who learned his craft so well at Carlisle and whose future seemed bright, only to come crashing down in the face of racism and discrimination when he went to Syracuse seeking work; and circus performers who went to Europe on an eight-month contract. These native peoples went to Europe. They were swept up in forces beyond their control. They were incarcerated briefly, apparently for their own protection, and they returned home. As America’s entry into the Great War approached, debates occurred over whether native peoples, who as yet were not citizens of the United States, could be drafted. The Onondagas’ declaration, justified by the base treatment their friends and families had experienced a couple of years before, quieted the issue for a time, until 1940, when it would surface once again.

Biographies of great men and women fill my bookshelves, life histories of people who did great things. They fought wars, won elections, discovered one thing, or destroyed another. The lives of famous people are linked to the events that they shaped, and that in turn shaped us. There is a place for books like these. You read them and I read them. We all have a list of them that we really like.

But think of your own life. What are the events that made you who and what you are? Have you done things, or had things happen to you, after which nothing ever could be the same? I ask my students this question each semester when I want them to consider the meaning of history. Always they ask for clarification. They want to know if I am interested in some public event, something “historical,” or something personal. I do not give them any guidance, for I want them to consider what constitutes a historical event. They will struggle with this because they are young and they have not lived through a lot. They might mention the attacks on 9-11, though all of them now are young enough that they can have no memory of that terrible day. Some will say the election of Barack Obama, which most of them think they remember. I will listen to them as they compare their lists. But I come back to my question.

struggle with this because they are young and they have not lived through a lot. They might mention the attacks on 9-11, though all of them now are young enough that they can have no memory of that terrible day. Some will say the election of Barack Obama, which most of them think they remember. I will listen to them as they compare their lists. But I come back to my question.

What are the events that made you who and what you are?

Was it a marriage? A divorce? A birth or a death or a relocation? A breakup? A particularly cruel thing said someone said to you or a particularly empowering statement of support? What events in their life left an impression, or a scar?

In writing a history that covers hundreds of years and focuses on a relatively small piece of what has become upstate New York, it is easy to lose sight of individual stories, and to focus on the forest much more than the trees. But it is in the small stories, the brief snapshots of ordinary lives, where we can find answers to some of the most important questions about our shared histories, and our shared humanity, across space and across time.

performers, was the Onondaga

performers, was the Onondaga  You can read a profile

You can read a profile