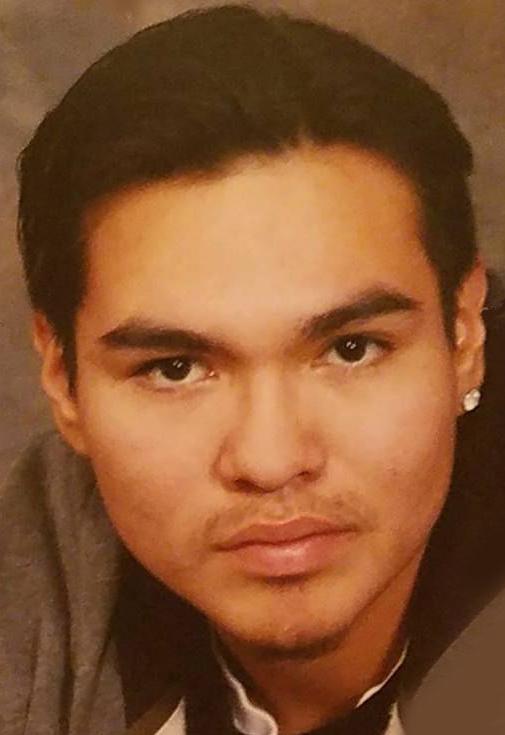

Brooke Crews butchered Savanna Greywind. Crews wanted a baby, and her young neighbor was eight months pregnant. On the night of 17 August last year she lured Greywind into her home. While Savanna was still alive, and passing in and out of consciousness, she cut the  child from her womb. When Crews’ boyfriend arrived, she presented him with the baby. “This is our baby,” she reportedly said. “This is our family.” Together, they cleaned up the blood. Together they disposed of Savanna’s clothing. And, together, they wrapped her body in plastic sheeting and dumped of it in the river, where kayakers found it sometime later.

child from her womb. When Crews’ boyfriend arrived, she presented him with the baby. “This is our baby,” she reportedly said. “This is our family.” Together, they cleaned up the blood. Together they disposed of Savanna’s clothing. And, together, they wrapped her body in plastic sheeting and dumped of it in the river, where kayakers found it sometime later.

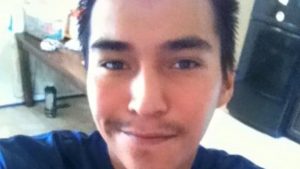

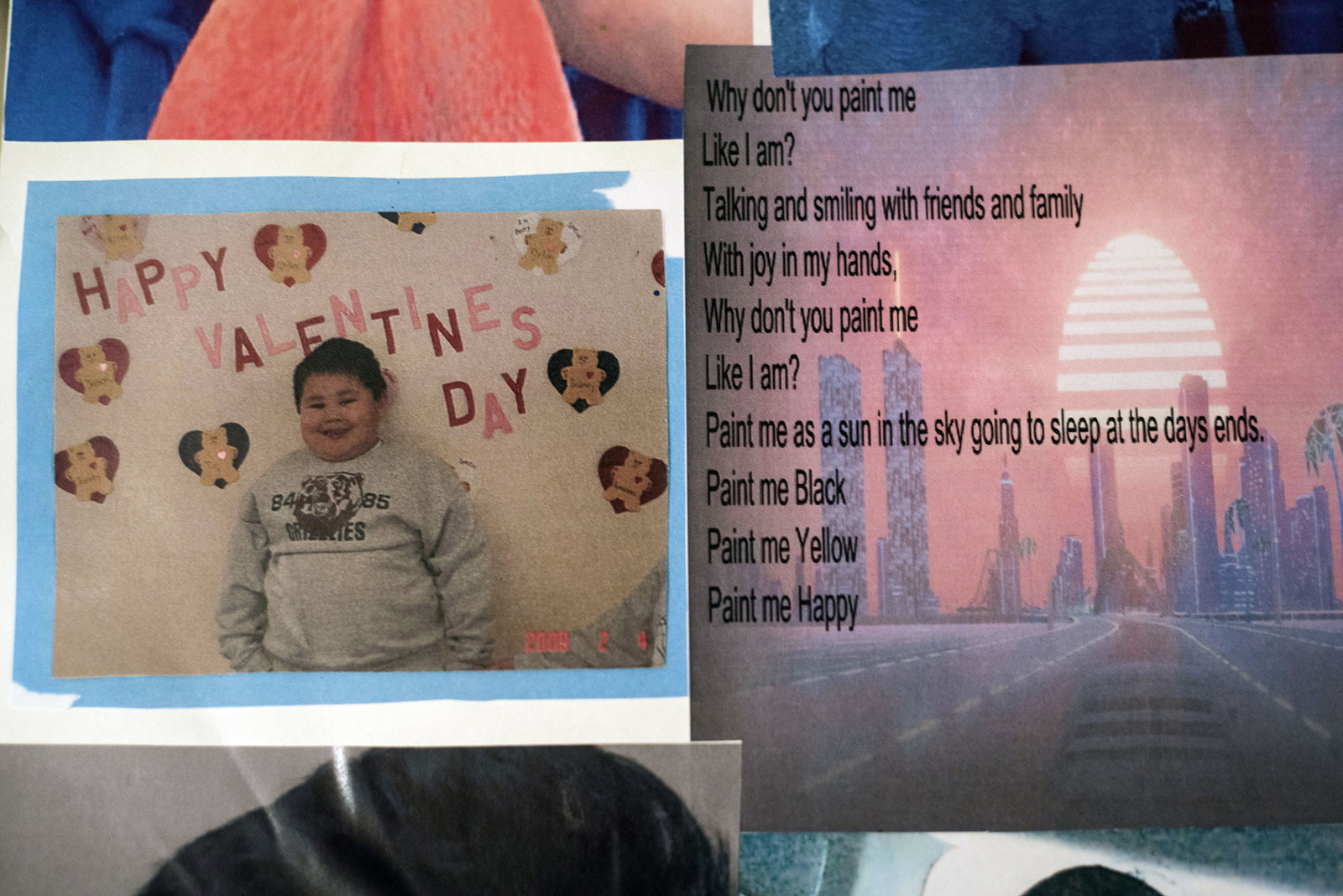

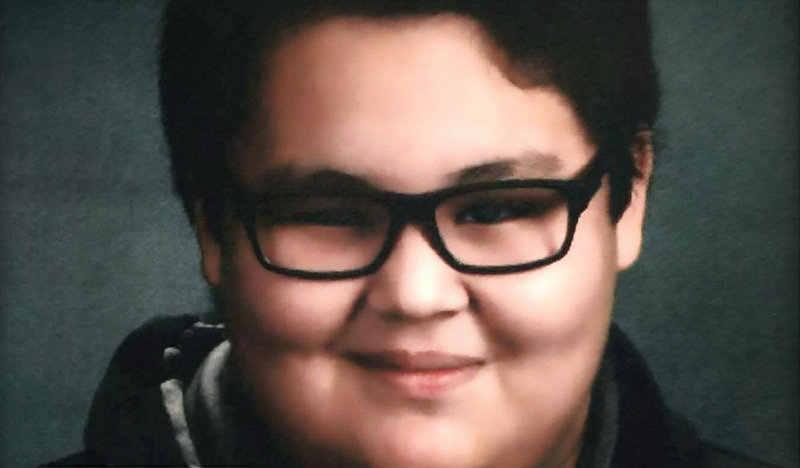

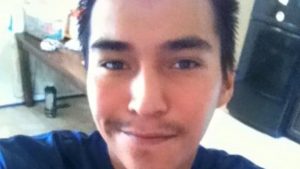

JUST OVER A YEAR BEFORE Savanna Greywind’s murder, another twenty-two year old, Colten Boushie, set out from his reserve west of Saskatoon. The car Colten and his friends were riding in got a flat tire, and the guys pulled into the farm of Gerald Stanley. Boushie and his friends had been drinking. They may have committed some petty thefts, though the testimony is confused. Young guys, engaging in mischief. Committing some minor crimes. (If you were ever a young adult, you probably have done this sort of stuff, too). But, here, at Stanley’s place, they seem to have  wanted nothing more than help fixing a flat tire. What happened next is a matter of dispute. Stanley said that the 70-year-old handgun he wielded in order to scare the young men off misfired. Others that he carried out an act of vigilante justice against a group of young men he feared had come to rob him. And others still believed that Stanley was an Indian-hating westerner from the Canadian Plains. Whichever, the case, Colten Boushie, who was seated in the vehicle’s front seat, died from a gunshot wound to the head. The bullet was fired by Stanley, from his old gun.

wanted nothing more than help fixing a flat tire. What happened next is a matter of dispute. Stanley said that the 70-year-old handgun he wielded in order to scare the young men off misfired. Others that he carried out an act of vigilante justice against a group of young men he feared had come to rob him. And others still believed that Stanley was an Indian-hating westerner from the Canadian Plains. Whichever, the case, Colten Boushie, who was seated in the vehicle’s front seat, died from a gunshot wound to the head. The bullet was fired by Stanley, from his old gun.

Last week, Savanna Greywind’s killer was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole. Stanley’s trial for the murder of Colten Boushie began last week. Both stories struck me as so evocative of the long and troubled history that I teach. Both stories scream with the echoes of the past.

The news is increasingly filled with stories of missing and murdered indigenous women and children. In response to Greywind’s murder, North Dakota Senator Heidi Heitkamp has introduced “Savanna’s Law,” which will “help address crisis of missing and murdered Native American women.” Specifically, the act would

- Improve tribal access to certain federal crime information databases. The bill would update the data fields to be more relevant to Native Americans, and mandate that the Attorney General consult with Tribes on how to further improve these databases and their access to them. The Attorney General would then submit a report to Congress on how the U.S. Department of Justice plans to implement the suggestions and resolve the outstanding barriers Tribes face in acquiring full access to these databases.

- Require the Attorney General, the Department of the Interior, and the Department of Health and Human Services to solicit recommendations from Tribes on improved access to local, regional, state, and federal crime information databases and criminal justice information systems during the annual consultations mandated under the Violence Against Women Act.

- Create standardized protocols for responding to cases of missing and murdered Native Americans. These protocols would take place in consultation with Tribes, which would include guidance on inter-jurisdictional cooperation among tribal, federal, state, and local law enforcement.

- Require an annual report to Congress with data. The report would include statistics on missing and murdered Native women, since there is little data on this problem and there isn’t a central location for keeping that information. The report would also include recommendations on how to improve data collection.

I wish Heitkamp well. I hope her legislation passes, and I hope it helps. It mainly aims at attempting to improve information about a problem that all acknowledge is poorly understood. That is a good thing, but it seems to me it is at best a half-measure. So much more than information is needed.

Heitkamp’s proposed piece of legislation addresses nonetheless deep and systemic problems that cut to the core of the Native American experience in North America. Native American women have always been objects of white violence. Long ago, for instance, George Percy told the story of how he ordered the Queen of Paspahegh stabbed to death after his men had earlier entertained themselves by throwing her children from the boat and shooting out their brains in the water. Edward Moseley, that mercenary who sold his services to the Puritan Saints during King Philip’s War, boasted about how he unleashed his war dogs on an Algonquian captive his men had taken. The dogs, Moseley noted, tore her to shreds. The mutilation of women’s bodies by American soldiers at Sand Creek: that, too, is part of a long, long story. Sexual violence rests at the core of this history and it continues: along the Canadian Highway of Tears and, if the spotty records are correct, on reservations across America. And in Fargo.

Brooke Crews stole Savanna Greywind’s baby. There is a long history of white clergymen, government officials, military officers, and bumbling do-gooders who have scooped up Native American children. Canada, much more than the United States, has started a discussion of the legacy of residential schools and the problems that continue to plague them. European colonizers and their colonial heirs long have collected the orphans whose parents they killed, sold them into slavery, bound them into servitude, and still, today, distribute them to white families in some states through broken and racist foster care systems.

Colten Boushie’s story, too, has so many ties to a vicious and violent past, for white people, throughout the history of this continent, have murdered native people. That reality runs through every book I have written, including Native America: Arthur Peach, the killer of a Narragansett messenger, Northern Neck racists who murdered Susquehannocks; Pennsylvania Frontiersmen who murdered Senecas with impunity, leading Federalist Timothy Pickering to lament that, for most white people living in close contact with native peoples, killing an Indian was no crime at all. Read the annual reports of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs: they are full of complaints from federal policy makers who felt powerless to stop the violence meted out on Indians by the white frontier population. It was frontier whites, American officials understood so well, who were responsible for frontier violence. Indians were usually victims.

You cannot miss this in the documents. It is all there. It is always there. And still it goes on. The police treated Boushie’s body with a callousness they would not use for white crime victims. And the police, when they came to Boushie’s house to tell his mother and father that their son had died, searched the house. They came in with guns drawn. They treated Mrs. Boushie with disrespect and cruelty. If the Boushies’ account is accurate, the Canadian police behaved like racist thugs. It is a heart-breaking tale that should shame police officials in Saskatchewan.

GREYWIND’S MURDER has provoked discussion and legislation in the halls of Congress to address a problem that native peoples have talked about for generations, but that Congress is only now starting to act upon. Boushie’s murder has caused deep-seated racial tensions to surface and has brought into the open, his grieving friends and families say, the sorts of racism and violence First Nations people face every day. The trial is receiving heavy coverage in Canada, where Boushie is being described as the “Rodney King of Canada.” Maybe something good will come from airing out these issues. That is what some hopeful people say. I am doubtful, because this violence has gone on forever. The headlines in the newspapers point out that the case has caused racial fears to increase, and that white people, one story said, are fearful of retribution. White people are worried. Fear of the other. Fear of the marginalized. Fear of the neighbors whose ancestral homelands you now occupy. I heard the expression of that fear when I lived in Montana: from my landlord, a feisty old woman who would not rent to Crows because, she said, if you let one in, soon you would have the whole tribe; from my students who, in unguarded moments, embraced baldly racist stereotypes; to the angry ranchers who extracted their livelihood from what had once been Crow land, and who refused to place themselves voluntarily under the authority of tribal officials. I hear it in small-town New York, too, where one can still see the faded “Upstate Citizens for Equality” sign along the sides of roads throughout the Finger Lakes.

We are historians. Many of us have heard the old line, that if we do not learn from the past we will repeat our mistakes. We study continuity and change, measured across time and space, in peoples, institutions and cultures. And, in Native American history, it is the continuities that stand out: with a Secretary of the Interior who views anything he cannot kill as something he might drill, and who views nothing as sacred save for his own conservative evangelicalism; with violence continuing across the continent; with a hostile legal system assaulting native nationhood; and with a Chief Executive whose infantile racism makes clear what many of us have long argued: this is a deeply racist country, and many of us continue to benefit from that systemic injustice. We have numerous examples of how difficult it will be to achieve meaningful change. That is realistic, not pessimistic.

My students are shocked when they read about stories like those of Savanna Greywind and Colten Boushie, and even more so when I take the time to place them in the context of a much larger, and much more violent, history than they have ever been taught. They seem empowered, some of them, and determined to “do something.” Others, they sense that the obstacles are formidable. And so on we go, teaching and writing, fighting against the dark belief that things will not get better. We choose the stories we want to tell. We must remember that.