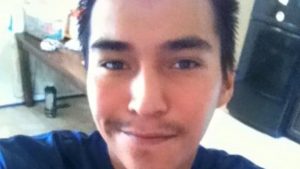

Late last Friday night the jury delivered its verdict in the trial of Gerald Stanley, the Saskatchewan farmer accused of murdering a young Cree man named Colten Boushie. Stanley shot Boushie in the head at close range and killed him. The all-white jury could have found Stanley guilty of murder in the second degree or manslaughter. Instead they acquitted him entirely.

It is not entirely clear what happened on Stanley’s farm that afternoon late in the summer of 2016, other than that there was an altercation involving Stanley, his son, and his wife with the four young people who drove onto the property, a cattle farm on Canada’s Plains.

Boushie and his friends had been drinking, that is for sure. One of them got out of the car and climbed aboard an ATV parked on Stanley’s farm, and tried to start it. One of them tried to get into a gold pickup truck that belonged to one of Stanley’s neighbors. He was a part-time mechanic and the truck needed some work. Stanley saw the car approaching and he watched them mess around with the truck and the ATV. He said he was afraid of the intruders, Indians, the other.

Nobody denies that Stanley went inside, grabbed a gun, loaded it with bullets, and, after a tussle, shot Colten Boushie in the head. Stanley said the gun misfired, that his finger was not on the trigger. Firearms experts disagreed. The gun was working properly, and could not have been fired without the trigger being pulled.

I am not a lawyer, and so I do not know all the legal ins-and outs of this case. It is plain to see that the witnesses were not entirely reliable, that both Stanley and Boushie’s companions changed elements of their stories over time. Based on the heavy press coverage in Canada, it seems that there is no way that a jury could have reached absolute certainty about what happened on the Stanley farm with one set of exceptions: Boushie and his friends entered Stanley’s property; they messed around with some of his stuff; Stanley went to get his gun; he fired that weapon three times, and one of those bullets struck Boushie, killing him.

Canadians have spoken much in recent years about “reconciliation,” about coming to terms with the atrocities the country and its provinces have committed upon native peoples. Prime Minister Trudeau has played a leading role in this effort. But when Niigaan Sinclair, a Professor of Native Studies in Manitoba, said that the verdict in the Stanley case was “unbelievable yet believable,” he got to the heart of the issue. Yes, Trudeau sent his warm thoughts and best wishes, his sympathies and his concerns, to Boushie’s family. But how does he expect First Nations peoples to take that seriously after the acquittal of Stanley? What is the point of talking about reconciliation and recovery and hope for a future informed by a thoughtful consideration of the atrocities and violence of the past, when the atrocious behavior and the violence continues?

It is a fair question for policy-makers in the United States, too, who have shown little willingness to talk about this nation’s colonial past.

When unmatched with real action and real results, “reconciliation” seems to involve white people asking native peoples to let them off the hook for the crimes of their ancestors. After this weekend especially, I cannot see any reason for them to do so. “Reconciliation” can’t just be, “It’s awful what we did to you, and let’s move on.” Rather, it must include, “it’s awful what we still are doing, and let’s talk about what needs to be done to make it stop.”

“Unbelievable, yet believable.” I get it. Those who watched the trial hoped for justice in the case of Colten Boushie, but it was a forlorn hope. It’s a sad but brutal fact: there is little evidence to support any belief that courts will get things right, that they will treat native peoples with justice and humanity. Rotten to the core. Ask those who grieve for Jason Pero, or John T. Williams, or Romeo Wesley or Zachary Bearheels. Colten Boushie is Canada’s Trayvon Martin, and Gerald Stanley its George Zimmerman.

I have made the case in the past, and it is an unpopular one here, that those of us non-natives who own homes in New York State are the beneficiaries of a systematic program of Indian dispossession. What Indians lost, white New Yorkers gained. Some are more guilty than others, but we are all complicit.

Sherman Alexie published a poem last week, on nearly the same day that Gerald Stanley’s trial commenced. “Hymn,” he called it, a call to love everything and for the radical hope that accepts as truth that we can feel and act on that love.

So let me ask demanding questions: Will you be

Eyes for the blind? Will you become the feet

For the wounded? Will you protect the poor?

Will you welcome the lost to your shore?

Will you battle the blood thieves

And rescue the powerless from their teeth?

Who will you be? Who will I become

As we gather in this terrible kingdom?

My friends, I’m not quite sure what I should do.

I’m as angry and afraid and disillusioned as you.

But I do know this: I will resist hate. I will resist.

I will stand and sing my love. I will use my fist

To drum and drum my love. I will write and read poems

That offer warmth and shelter of any good home.

I will sing for people who might not sing for me.

I will sing for people who are not my family.

Colten Boushie was the victim of a crime that had its origins long ago. It is historic. The criminals, and all their accomplices in and out of all the years, they remain at large, untroubled, unworried, guilty, and free.