And about that college in Montana. It is not that the people in my department did not care about my research. It’s that they saw any small success that came my way as something to resent. Sometimes I told myself that they saw my work through a lens of insecurity, that my productivity reflected on their own lack of productivity. But I was not all that productive in Montana. Anyways, I know now that this was never the case. They were just mean-spirited bastards, and I let those assholes get under my skin.

I have thought about this a lot in light of the Netflix show “The Chair.” I saw someone on twitter ask about Bob Balaban’s character, the starchy and elitist professor of American literature Elliot Rentz. Pembroke University, the fictional setting for “The Chair,” looks like paradise compared to MSU-Billings, which at the time I taught there was a demoralizing hellscape led by a dunce of a President and a dumbbell Dean.

My department consisted of two Jeopardy Champions. One, who was working on a bibliography of lynching, insisted that the infamous Willy Horton advertisement was perfectly acceptable and had nothing to do with race in America. The other was a Harvard-trained historian of the French Revolution who had been denied tenure at two other institutions before he landed in Billings. He did not drive, and relied on students to drive him around. He liked to hang around the dorms. When I left Billings, he warmly congratulated me, told me how great my new department chair was, and then scurried off to tell him how awful I was. My new chair assured me that this reflected badly on everyone in Montana but not on me.

There was also in the department an Iraqi Seventh-Day Adventist who believed that African Americans were moving to Billings because it was an easy place to commit crimes, and a Missouri-Synod Lutheran pastor who proudly claimed that being a professor “was the best part time job in the world.”

There are all sorts of people in the United States who do not want to hear anything bad about the American past. These people can make our jobs difficult. What I think is often overlooked, however, are the barriers to doing the work we do inside the academic institution: administrators who don’t want to draw the dangerous attention of dingbats in the legislature or on the Board of Trustees by discussing controversial subjects; penny-pinching college leaders unwilling to make the investments, personally and financially, to make the college a welcoming space for Indigenous students; and students, even in areas where Native Americans are the largest minority group of campus, who sometimes care nothing at all and Indigenous peoples and their communities. Racism of these stripes was a genuine repressive force in Billings.

I taught there for four years, in an era when it seemed the internet was still in its infancy, without cell phones, and with no computer provided by the college. And because I was a single parent for three of my four years, I could easily stay out of the loop. I was really busy, and Billings felt far away from everything. The right-wingers like Lynne Cheney and Pat Buchanan who, at that time, denounced “politically correct” history, really did not affect me much at all. Not directly, anyways. What mattered more was teaching a subject that was considered provocative, in a bad way, at an institution presided over by leaders who actively discouraged discussions raising challenging questions about the American past.

I was hired to teach the history of Early America, from the colonial period through the “Age of Jackson.” It just so happened that not only had my predecessor left, but another guy, who taught Native American history was retiring. During my on-campus interview, he drove me forty miles to a bar in Columbus, Montana, where we split a six pack of Budweiser. He was a good guy, I think. He left me a ton of books. He taught the subject as little more than the history of the Plains Wars.

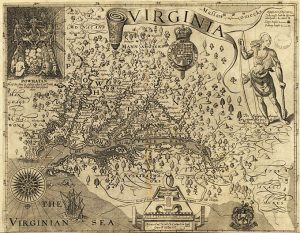

That wasn’t me. I focused my research on the seventeenth century. I was turning my dissertation into a book. I had a much broader coverage in mind. What do to, then, when the Dean of the College of Liberal Arts, in a meeting after my first contract renewal, told me that she wanted to see more “relevant” and “applied” research? No one in Montana cared about the history of the Chesapeake or New England, she seemed to suggest.

Contract renewals were tough. Each year my contract came up for renewal. Each year, the two Jeopardy champions voted to fire me. Each year, the Pastor and the Seventh-Day Adventist voted to keep me around. One student member of the committee, God bless them, voted each year to save my job. It was tense, and I needed every ally I could get.

So I tried to play ball. I started speaking with some of my students who drove to Billings from the Crow Reservation. I learned a lot, things I had read in no scholarly monograph. What came from these conversations was the racism these students faced–in high school in Hardin, Montana, in the city of Billings, and in classrooms at my college. Perhaps there was a story to tell here.

I cannot remember the details. There had been some event at Hardin High. The non-Indigenous students stayed home from some sort of cultural awareness day, their truancy excused by their parents. The Crow kids, as kids will do, made some noise about racism. The next day, distributed throughout Hardin, were copies of some white nationalist text like The White Man’s Bible. I went down to Hardin. I tried to learn more. I tried to blend in and listen. I talked to a few people about racism in Hardin. I had gathered some great insights about racism in a reservation border town. This struck me as immediately significant and relevant to life in Montana and in a host of western states. In the end, it was too difficult to do the research. I would have had to spend a lot of time in Hardin, an hour’s drive from where I lived, and my family life would not permit that. But the bigger barrier was the Dean, who somehow had become the Provost, or something like that. I ran into her, somewhere on campus, whcih almost never happened, and told her about the project. I could see clearly from her reaction that this was not what she had in mind at all.

I left Billings in 1998. At Geneseo, where I have taught pretty much ever since, I have been able to do what I wanted to do. We do not have a lot of money, but in every other way my research has been supported.

And that’s the key point. To do research requires a network of support. It is easier for us to do our work when we have interested colleagues who encourage us and provide pointed criticism, administrators who recognize the value of what we do. With that assistance, we can stand up to the racists, the haters, the bigots and trolls. That part of the job becomes easy. It’s when these things are missing that our academic lives can be miserable.