I was raised in a Catholic household by parents who are now Unitarians. I was never confirmed, was withdrawn by my parents from Our Lady of Assumption school after I finished sixth grade, and long ago left the church. There is nothing that I can accept as true in the Apostles’  Creed I was expected to memorize as a child.

Creed I was expected to memorize as a child.

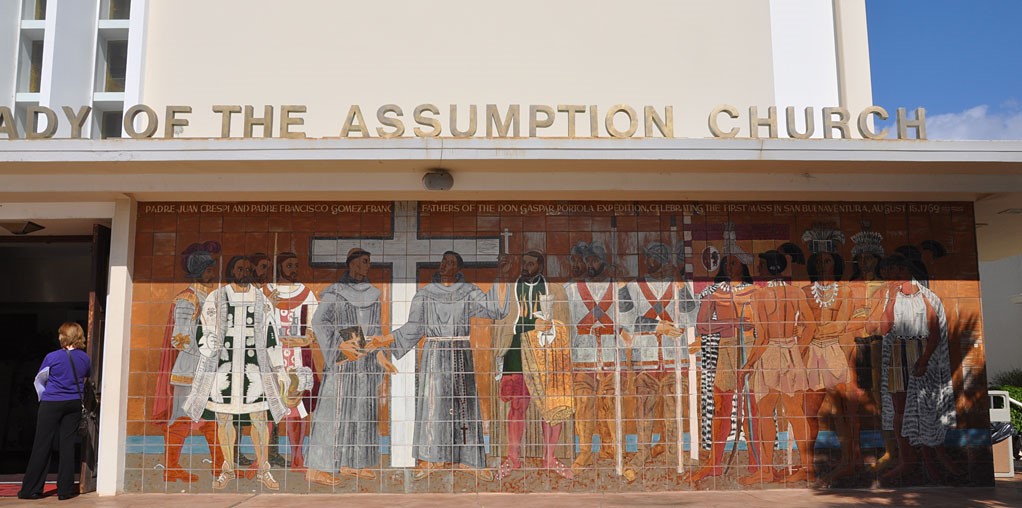

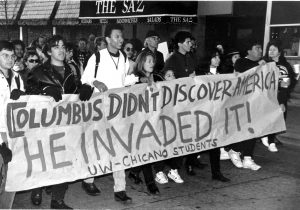

I write this to let you know where I am coming from when I tell you I am nonetheless sometimes disturbed by uncritical and decontextualized denunciations of churches in general and the role they played in the encounter between natives and newcomers. Religious people did hideous things in the name of their particular variants of Christianity, a fact which no historian of Native America can deny. Still, though there are plenty of villains, as in most matters of the soul this is no simple morality play. It is worth taking the time to get it right. There are some truly outstanding historians writing about this religious encounter, but the sophistication and subtlety of their work has not trickled down to popular understandings of the incredibly diverse array of relationships that developed between different native peoples and organized Christianity.

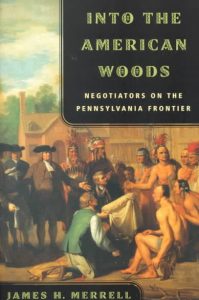

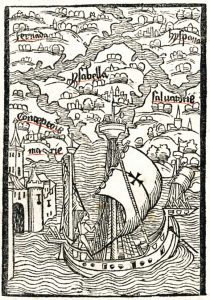

For the past several years, for example, I have been conducting research on a history of the Onondaga Nation. There is little doubt that the Jesuit fathers who came to Onondaga in the middle of the seventeenth century hoped to sneak in through the “Smoke Hole” of the Onondaga Longhouse. They wanted to minister to the Wendat adoptees residing in Onondaga communities. The Onondagas, much later, allowed several Protestant denominations to operate missions on their reservation but they did not allow the Catholics. “It’s because of what  they did to us,” one person with whom I spoke told me. But the Jesuit missionaries, at the end of the day, came to Onondaga only because the Onondagas permitted them to do so. They planted their mission on an elevation overlooking Onondaga Lake, because that is where the Onondagas permitted them to do so. Wendat adoptees looked at and listened to the priests but the Onondagas took little interest. The priests, indeed, felt isolated and threatened. They used the church they had constructed to secretly build the canoes they would use when they fled one winter’s night from Onondaga. The Jesuits had that little influence upon the Onondagas. Priests did not always dominate, intimidate, or exercise any control over native communities. Sometimes they were barely tolerated. At other times they did exactly what they were told by their native hosts. They stayed on only so long as they were tolerated, and native peoples had complex reasons for wanting them around, some of which had nothing to do with acceptance of their religion. When we focus upon the bigotry of the missionaries, and when we cast the story in simplistic terms, we can lose sight of how native peoples understood their encounters with Christianity.

they did to us,” one person with whom I spoke told me. But the Jesuit missionaries, at the end of the day, came to Onondaga only because the Onondagas permitted them to do so. They planted their mission on an elevation overlooking Onondaga Lake, because that is where the Onondagas permitted them to do so. Wendat adoptees looked at and listened to the priests but the Onondagas took little interest. The priests, indeed, felt isolated and threatened. They used the church they had constructed to secretly build the canoes they would use when they fled one winter’s night from Onondaga. The Jesuits had that little influence upon the Onondagas. Priests did not always dominate, intimidate, or exercise any control over native communities. Sometimes they were barely tolerated. At other times they did exactly what they were told by their native hosts. They stayed on only so long as they were tolerated, and native peoples had complex reasons for wanting them around, some of which had nothing to do with acceptance of their religion. When we focus upon the bigotry of the missionaries, and when we cast the story in simplistic terms, we can lose sight of how native peoples understood their encounters with Christianity.

Still, we who teach and write about Native American history need to discuss the misdeeds of the various religious denominations, however uncomfortable that might be for some of our students. Missionaries, after all, hoped to cause a huge chunk of Native American identity to disappear. The story of Christian missionaries in Indian country is often one of bumbling good will, or cultural arrogance and spiritual bigotry. They attempted to erase Native American spirituality. And this bigotry is fundamental to the entire story of Christian missions to native peoples in North America. And the abuse and the violence, too: there are stories there that must be told.

I have just finished watching, for instance, a Netflix documentary series called “The Keepers,” a deeply unsettling story of rape and murder at a Catholic girls’ school in the Diocese of Baltimore. It is a story of clerical sexual abuse on steroids that long predated the Spotlight investigation in Boston and the exposure of this widespread rot at the Catholic Church’s core. And it is the story of the generational trauma this sort of abuse and criminality can cause.

My students are pretty attuned to what’s available on Netflix, and it is worth telling them, I think, that the problem of clerical sexual abuse highlighted in “The Keepers” extended into Indian country. Just a couple of months ago a Montana newspaper, the Great Falls Tribune, produced a series investigating how the Catholic Church used Indian reservations in Montana as “dumping grounds” for predatory priests. In my American Indian Law and Public Policy course at Geneseo I expect my students to watch the PBS Frontline documentary “The Silence,” reported by Mark Trahant, about a small Catholic church in a remote Alaska native village overseen by a number of serial abusers, and the wreckage the priests and their accomplices left behind. It is painful to watch. When I have shown the film in class it has left my students stunned, struggling to find the words to describe their feelings.

For many years I have used in class Luke Lassiter, Clyde Ellis and Ralph Kotay’s book, The Jesus Road: Kiowas, Christianity, and Indian Hymns. The University of Nebraska Press published the book with a CD including recordings of these the Christian hymns sung by the Kiowas. What the book does, beautifully and meaningfully in my view, is show how in the Kiowas’ hands Christianity became a Native American religion, the center of their lives, and the heart in a heartless world. It is a story that complicates the narrative of Christian missions my students heard in high school, if in fact they heard anything there at all. There are other books and essays that can serve a similar function. There are several chapters in Matthew Dennis’s Seneca Possessed that provide a nuanced portrait of the Quaker missions at Allegany and Cattaraugus early in the nineteenth century; Linford Fisher’s The Indian Great Awakening: Religion and the Shaping of Native Cultures in Early America is outstanding on New England in the eighteenth century; Steven Hackel’s study of the Spanish missions in California, Children of Coyote, Missionaries of St. Francis; Allan Greer’s Mohawk Saint on one of the Catholic Church’s newest saints; Dan Mandell’s Behind the Frontier and Tribe, Race, History; articles by Robert James Naeher and Harold Van Lonkhuyzen that appeared in the New England Quarterly; the chapter on Kahnawake in David Preston’s Texture of Contact; Tammy Schneider’s article on the Mohegan Joseph Johnson which appeared in Reinterpreting New England Indians and the Colonial Experience, edited by Neil Salisbury and Colin Calloway; David Silverman’s Red Brethren and Faith and Boundaries; Laura Stevens’s The Poor Indians and Erik Seeman’s book on Death in the Atlantic World are all outstanding. Recent works worth checking out include Benjamin Kracht’s Kiowa Belief and Ritual; Louis Warren’s God’s Red Son and Mark Clatterbuck’s Crow Jesus: Personal Stories of Native Religious Belonging. This list is far from exhaustive, and if you have other suggestions, I will be happy to share them.

Religion can be many things. It can be, in its most formal sense, a set of rules and regulations, things to do and things to avoid if one wants to achieve salvation. It can be judgmental and cruel or, at its best, a message of love, for everybody, of liberation and equality and compassion. You might dismiss it as myth or nonsense, or as a salve or an opiate to calm your fears and ease your pain. Or it might give you the confidence and courage to do extraordinary things. It can be all of these things, I suppose, to each of us at different points in our lives. And none of the beliefs you hold about religion or, for that matter, about politics, economics, or society, need keep you from doing good historical research if you are honest, as free from bias and prejudgment as you can be, and if you keep your eyes, your ears, and your heart open. We must all strive to understand the people we write about, even those we detest. Compassion, understanding, empathy: they are important tools of the historian’s trade. And when you understand, yes, you must condemn and criticize where it is warranted and, above all, you must teach these disturbing stories when your training and the instincts you have honed leave you convinced that these stories matter. If you are honest, you have nothing to fear.