Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote a destructive opinion in the case of Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta that, simply put, threatens the entire field of American Indian law as it has developed and devolved in this country over the course of two hundred and forty-six years. The Supreme Court’s recent term has been nothing short of revolutionary, in all the worst ways. And it is going to get worse.

“Indian country is part of the State, not separate from the State” Kavanaugh wrote, and “as a matter of state sovereignty, a State has jurisdiction over all of its territory, including Indian country.” Keep these words in mind, for they have explosive implications.

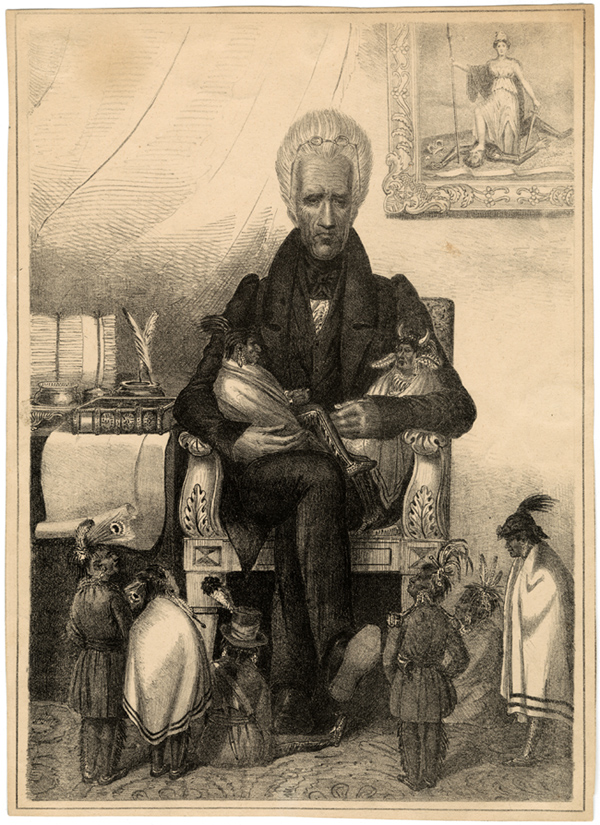

Kavanaugh’s words in the Castro-Huerta case are nearly identical to the position Andrew Jackson took shortly after his inauguration in March of 1829. The United States, his secretary of war John Eaton told the Cherokees, would never halt a state in the exercise of its powers over Native Americans residing within its borders because “that is not within the range of powers granted by the states to the general government.” Indians must submit to the laws of the state they lived in or leave. Chief Justice John Marshall slapped that idea down three years later in his monumental opinion in Worcester v. Georgia, still the single most important decision in the field of American Indian law.

There is a concept with which all students of American Indian law are familiar: Congressional plenary power. It is based on Article I, Section 8 of the United States Constitution, in which the American people gave to Congress the right to regulate “commerce with the Indian tribes.” Basing his decision in Worcester on that constitutional clause, Marshall said that the Cherokee Nation is a “distinct community, occupying its own territory, with boundaries accurately described, in which the laws of Georgia can have no force, and which the citizens of Georgia have no right to enter, but with the assent of the Cherokees themselves, or in conformity with treaties, and with the acts of Congress. The whole intercourse between the United States and this nation, is, by our Constitution and laws, vested in the government of the United States.” The conduct of Indian affairs, then, belonged strictly to the United States, and sovereign Indigenous nations stood between the national and the state governments in the constitutional framework of the United States. Native American sovereignty was real, it was constitutional, and it mattered.

There were good reasons for this. During the Confederation era and thereafter, the individual states pushed the Indigenous nations that lived within their borders to the brink of wars the United States could hardly afford to fight. The worst military defeat suffered by the United States at the hands of Native American opponents came not along the Little Bighorn in 1876 but along the Maumee, in 1791. Powerful Indian nations posed an existential threat to the United States. George Washington and all his successors except for Andrew Jackson, looked for ways to rein in the states, which they believed posed the gravest threat to frontier order.

If you jump forward a few years and read the Annual Reports of the Commissioners of Indian Affairs, you will see the same sentiments expressed. Federal control over Indian affairs was necessary because locals consistently stirred up trouble with Indigenous peoples. They stole lands and committed unspeakably cruel acts of violence.

Over the years, the idea that states can not intrude into Indian affairs has eroded considerably. For instance, tribes have no right to prosecute non-Indians who commit crimes on their lands, the Court held in 1978. Only in certain specific circumstances do tribes possess regulatory authority over the activities of non-Indians who do business on their lands. And we should be clear—federal plenary authority is hardly a good thing. Sure, it restrains the states, which historically have always been worse, but plenty of evil has been done by the United States.

American Indian law is not always a complicated subject. There are a few simple principles that, once mastered, can help you make your way through the morass. For much of this nation’s history, Indian tribes could essentially exercise any power they wanted unless they were specifically prohibited from doing so by a treaty or an act of Congress. That is Marshall’s logic in Worcester, and it held up for many years. Some lawyers call this principle explicit divestiture. In 1978 Justice William Rehnquist added the idea called implicit divestiture: Indian nations can exercise any power they want, unless explicitly prohibited from doing so by a treaty or act of Congress, or if the power in question is somehow inconsistent with their status as “domestic dependent nations.” A starkly drawn line between federal and state authority has been blurred.

As Stephen Pevar put it in his useful ACLU Handbook The Rights of Indians and Tribes, there are five basic principles about criminal law in Native American territory:

- Because of the plenary power doctrine, Congress can decide which governments exercise criminal jurisdiction in Indian Country, and Congress can increase or decrease the amount of power tribes, states, and federal governments might possess.

- Tribes have the inherent sovereign right to exercise criminal jurisdiction over its own members, with the exception of certain “major crimes” which Congress made federal crimes.

- Neither the state, according to Marshall’s Worcester decision, nor the federal government, according to the case of Ex Parte Crow Dog can exercise any criminal jurisdiction over tribal members for crimes committed in Indian Country unless Congress has explicitly given them that power.

- Indian tribes have no criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians unless Congress has specifically allowed for the exercise of that power, as it did in a limited manner in the Violence Against Women Act.

- Finally, owing to the 1881 McBratney decision, a state may exercise jurisdiction over crimes committed on reservations by non-Indians against non-Indian victims.

Kavanaugh’s opinion would have made Andrew Jackson proud. States are sovereign. They are free to conduct their elections in any manner they choose, to draw electoral districts however they like, to choose on their own whether or not to recognize the fundamental rights of women, and to conduct business with the Native American nations that live within their boundaries (and predate the existence of the state) however they choose. Victor Manuel Castro-Huerta, a non-Indian residing in Indian Country, is an awful person, an abuser of a Native American child and a man who injured his daughter in ways that are horrifying to read. Because of last year’s McGirt decision, much of the eastern half of Oklahoma remained “Indian Country” because Congress had never disestablished the Creek Reservation. The state wanted to prosecute Castro-Huerta, did so, and sentenced him to thirty years in prison. When McGirt forced his conviction to be overturned, federal authorities tried him and sentenced him to seven years in prison. The state appealed to the Supreme Court, and Kavanaugh said that states have concurrent jurisdiction with the United States over crimes committed by non-Indians in Indian territory. States had never relinquished that power, so with them it remained. That tribes predate the states did not matter one bit to the Court majority. That tribes had their own governing institutions, their own legal systems, and their own very real need to maintain law and order on their lands did not matter at all. That most tribes had never relinquished the right to prosecute outsiders who commit crimes on their land? Nope. Did not matter to Kavanaugh. No justification was needed to dismiss Indigenous nationhood. The Court’s Radical Right made might make right.

Kavanaugh increased state authority on reservations over crimes committed by non-Indians with Indian victims, a field that previously could be prosecuted by the United States. It is important to realize this. The Castro-Huerta decision is as much an assault on the plenary power doctrine as it is an assault on the rights of Native American nations. And you should expect things to get considerably worse in the next year or two.

The Brackeen case, a legal battle in which the fate of the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978 hangs in the balance, I fear is precisely the sort of Indian law case for which Justice Clarence Thomas has been waiting. Thomas is the most anti-Indian of the Court’s nine justices. The case that I worry about most is Brackeen v. Haaland. The Court will hear the Brackeen case in October.

The Supreme Court’s conservative majority has done an immense amount of damage to its own legitimacy owing to its recent decisions. Brackeen focuses on an important 1978 statute known as the Indian Child Welfare act, or ICWA, for short. I worry that the Court will, with Brackeen, deliver a fatal blow not only to ICWA, but the entire foundations of American Indian Law. That will hurt the Court, but it will hurt Indigenous peoples even more.

By nearly every objective measure, ICWA has been a great success. Congress enacted the ICWA in 1978, an important piece of legislation designed to halt the traumatic removal of native children from their homes through fostering and adoption. The problem was severe.

Dakota Sioux at Spirit Lake, about whom I write in Native America, asked the Association of American Indian Affairs to investigate, and the AAIA reported that of the 1100 Dakotas under the age of 21 who lived at Spirit Lake in 1968, 275 had been removed from their families. In states with large Native American populations, the AAIA found that “child welfare” agencies had removed between 25 and 35 percent of children from their homes. Native peoples organized to halt this highly destructive practice, and the battle for the passage of the ICWA, according to its best historian, “represented one of the most fierce and successful battles for Indian self-determination of the 1970s.” The legislation committed the United States “to protect the best interests of Indian children and to promote the stability and security of Indian tribes and families by the establishment of minimum standards for the removal of Indian children from their families and the placement of such children in foster or adoptive homes which will reflect the unique values of Indian culture.” Native American children, under the legislation, must be placed with family members, with members of their tribe, or with members of another native nation, before they are placed in the care of non-Native American foster parents.

Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, and a growing number of conservatives, argue that the law has gone too far. “In practice, the ICWA compels states to disregard the ordinary approach of determining a child’s best interest and to treat Native American foster children differently based on nothing more than their race,” Paxton wrote in an editorial that appeared in the Washington Post early in 2019. “The law gives Indian tribes a trump card to play in any state child-welfare proceeding, allowing them to dictate outcomes whenever a child is or even could be a member of a tribe.” For Paxton, it’s a states rights issue. “If no biological family members can be found, the law requires state courts and agencies to make a priority of adoption by other ethnically Native American families.”

“Native American children, strictly because of their race, thus can be kept apart from foster families eager to adopt them. If federal law treated any other class of people this way, it would be roundly condemned, and rightly so. According to the Department of Health and Human Services, 10,529 American Indian/Alaska Native children were in foster care in fiscal 2017.

Some claim that the ICWA relies on a political designation, rather than a racial one, because a tribe is a political entity. But no political or cultural link to a tribe must exist for the Indian Child Welfare Act to apply to a given child. Tribal eligibility — determined in virtually every case by genetic ancestry — is sufficient. The idea that the ICWA relies on a political designation rather than a racial one is further undermined by the fact that if no family from the child’s tribe volunteers to adopt, any Native American from any tribe, anywhere, takes automatic precedence over a non-Native American couple. This requirement relies on racist and reductionist assumptions about the supposed interchangeability of drastically different tribal cultures.

You would not know it from Paxton’s piece, but his opinions are those of a distinct minority. Twenty-one state attorneys-general, along with thirty child welfare organizations, 325 tribal governments and fifty-seven tribal organizations have expressed their support for the Indian Child Welfare Act. The law, they write, “was designed to reverse decades of cultural insensitivity and political bias that had resulted in one-third of all Indian children being forcibly removed by the government from their families, their tribes and their cultural heritage.” The law was a signal achievement, and it has done its job. The ICWA ensures the “stability and cohesion of Tribal families, Tribal communities and Tribal cultures,” in the face or organizations and entities that have sought their destruction.

Beginning in the second half of the twentieth century, the Court opened the door to increasing state power over native peoples and their lands. Conservatives on the Court have worked consistently to reduce the power of tribal governments. Justice Thomas, it seems to me, has led the way, making the case in a number of decisions over his long tenure on the Court that the plenary power doctrine is unconstitutional.

Why do I feel that way? First, Thomas believes that much of the Court’s jurisprudence on Native American questions lacks constitutional grounding. Indeed, Thomas on more than one occasion has questioned the constitutionality of the “Plenary Power” doctrine.

In the 2004 case of US v. Lara, for instance, Thomas said that he was troubled by the “premises and logic of our tribal sovereignty cases.” Thomas felt that the court had not attempted to remove the important tensions between two assumptions that struck him as contradictory. “First, Congress (rather than some other part of the Federal Government) can regulate virtually every aspect of the tribes without rendering tribal sovereignty a nullity.” It did so, however, while it maintained that “the Indian tribes retain inherent sovereignty to enforce their criminal laws against their own members.”

Thomas could not accept the Court’s assertion “that the Constitution grants Congress plenary power to calibrate the ‘metes and bounds of tribal sovereignty.’” He had read the Constitution and in it, he wrote, “I cannot locate such congressional authority in the Treaty Clause. . . or the Indian Commerce Clause.” The phrase– “commerce”–had been defined too broadly.

Furthermore, Thomas questioned the constitutionality of the 1871 enactment through which Congress put an end to treaty-making, because “the making of treaties, after all, is the one mechanism that the Constitution clearly provides for the Federal Government to interact with sovereigns other than the States.”

Thomas reviewed the Lara reasoning, and that used by the Court in its antecedents: Oliphant, US v. Wheeler (1978), and Duro. He was skeptical. In his conclusion, Thomas wrote,

The Court should admit that it has failed in its quest to find a source of congressional power to adjust tribal sovereignty. Such an acknowledgment might allow the Court to argue the logically antecedent question whether Congress (as opposed to the President) has that power. A cogent answer would serve as the foundation for the analysis of sovereignty issues posed by this case. We might find that the Federal Government cannot regulate the tribes through ordinary domestic legislation and simultaneously maintain that the tribes are sovereigns in any meaningful sense.

In Adoptive Couple v. Baby Girl (2013), Thomas again considered the constitutional basis for plenary power, in another case involving the 1978 Indian Child Welfare Act. “Although the Court has said,” he wrote, “that the central function of the Indian Commerce Clause is to provide Congress with plenary power to legislate in the field of Indian affairs,” neither the text nor the original understandings of the Clause “supports Congress’ claim to ‘plenary’ power.” The contested adoption proceedings at the heart of the Baby Girl case involved neither commerce nor tribes, and Thomas believed that “there is simply no basis for Congress’ assertion of authority over such proceedings.”

Three years later, in the case of US v. Bryant, Thomas once again returned to these questions. Thomas’s Bryant opinion is heavily cited in the Texas petition. Congress’s “purported plenary power over Indian tribes,” Thomas wrote, rests on shaky foundations. “No enumerated power–not Congress’ power to ‘regulate commerce…with Indian tribes,’ not the Senate’s role in approving treaties, nor anything else, gives Congress such sweeping authority.” Thomas found the origins of this claim to power in the 1886 Kagama decision, which upheld the constitutionality of the previous year’s Major Crimes Act. Native American weakness, in that case, justified the extension of federal power. The government’s power, the Kagama court wrote, “over these remnants of a race once powerful, now weak and diminished in numbers, is necessary to their protection… It must exist in that government, because it has never existed anywhere else.” That seemed like a claim to power that was not supported by the Constitution and it was time, in Thomas’s view, to review these decisions.

And in an 2017 dissent in a case involving the Secretary of the Interior’s decision to take 13,000 acres of Oneida land in New York into trust, Thomas again criticized the Court’s Indian Commerce Clause rulings. Allowing the federal government to take land within a state into trust on behalf of an Indian tribe, Thomas argued, could not be supported by any language in the Constitution, and it would have shocked the “Founding Fathers” to “find such a power lurking in a clause they understood to give Congress the limited authority to ‘regulate trade with Indian tribes living beyond state boundaries.”

So in his petition to the Supreme Court, the Texas Attorney General has built upon a foundation ready-made by Justice Thomas. “Relying on the Indian Commerce Clause,” the petition reads, “the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978 creates a race-based federal child-custody system and requires the states to implement it for all Indian children who appear before their courts.” Relying on a district court ruling that found ICWA unconstitutional, Texas argued that “no provision of the Constitution gives Congress `plenary power’ over Indian affairs.”

Texas wants clarity, it says. It wants to do what’s best for the “most vulnerable among us—children residing in dangerous circumstances.” Rebecca Nagel in her excellent “This Land” podcast, argues that this case is about far more than children. It’s about an assault on the entire apparatus of federal control over Indian affairs. I think she is right.

Read colonial laws. Read the writings of the royal commissioners who visited Virginia in the wake of Bacon’s race war against all Indians, or the writings of Henry Knox, or the annual reports of the commissioners of Indian Affairs during the second half of the nineteenth century. In all you see an effort by authorities representing the state to control the activities of frontier residents, both Native and newcomer. They blamed frontier whites for frontier violence. The goal of imperial control and then federal control over the conduct of Indian policy always was contested by provincials, by the inhabitants of the territories, and the citizens of the sovereign states. If the Supreme Court chooses to hear the Brackeen case, it could strike down the important Indian Child Welfare Act. It also could, in the process, decide that the plenary power doctrine is unconstitutional. In terms of Indian law, the consequences of this would be earth-shattering.

Think about it this way: what if the Constitution does not give Congress plenary power over Indian affairs? Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution says that “Congress shall have the power to regulate Commerce with foreign nations and among the several states, and with the Indian tribes.” According to constitutional scholar Gregory Ablavsky, the Founding Fathers used the word “intercourse” far more often than they did the word “commerce,” and that this word has a wider range of meanings. There is a lot of truth to that. The first federal Congress, in order to flesh out the sparse language of the Constitution, enacted in the summer of 1790 the first of a series of “Indian Trade and Intercourse Acts.” But look at the legislation. Seriously. Read it. The Indian Trade and Intercourse Act regulated those instances where native peoples and newcomers came into contact by limiting the actions of non-Indians: Americans could not trade with Indians without a license, for instance, and purchases of Indian land could be made only by the national government. In the Indian Trade and Intercourse Act, one could argue that Congress asserted no power to regulate the internal affairs of any native nation.

Maybe plenary power is a lie, a fiction, or a fraud. Maybe Thomas is right, in that the Court, over many years, has just sort of made stuff up to suit its purposes.

I have many friends who spend a great deal of time decrying the so-called “Doctrine of Discovery,” the notion that somehow the Europeans’ discovery of America gave them title to land on this continent. Many of them are calling for a repeal of the doctrine, and for its repudiation by the churches who originally espoused it. Is the notion of “plenary power” any less a fiction? Can it be justified in any way from the sparse language in the Constitution which, Justice Thomas has asserted consistently throughout his career (whatever you think of him), truly matters? Justice Thomas has asserted that the Court’s Indian Commerce Clause rulings are built on a fiction, that they stand without justification in the Constitution’s language.

Perhaps, rather than placing that power in the hands of state governments, as Justice Thomas seems to suggest, it more accurately could be asserted that the Constitution recognized native nations as separate polities, over which it exercised no control and no authority, save for an authority superior to the states to regulate interactions between these native nations and the American people. Congress, rather than the states, could regulate commerce and intercourse by regulating the activities of American citizens, but it could claim no power to do anything within and over native nations themselves, because no such power is stated in the Constitution. If the Doctrine of Discovery is a racist sham, as its critics assert, then perhaps the Congressional plenary power doctrine is a falsehood, too, a misinterpretation of framers’ intent and a complete fiction that the United States ought to address if it wants honor its endorsement several years ago of the UNDRIP. And if it is a fiction, we are left with one conclusion about the federal government’s claim to exercise absolute authority in the realm of Indian affairs: that its claim to plenary power rests on nothing more, at the end of the day, than brute force. Colonialism is alive and well.

These questions will not be addressed in the way I would like when the Court rules on the Brackeen’s appeal. And we must keep in mind why Texas is devoting so much energy to combating ICWA. What is in it for Texas? If the court hears the case, and Thomas persuades his colleagues on the Court to follow the logic of his rulings over the years, the Supreme Court could hold that the entire plenary power doctrine is unconstitutional, that under the 10th Amendment, ” powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the states respectively, or to the people” and throw the regulation of Native nations over to the states. Their lands, and the mineral wealth that lies beneath, would be subject to state legislatures who seek to skim the cream off of any prosperity that could conceivably come to Indian country. These states could rush to place Native peoples on the same plane as the rest of their citizens, not as members of Indigenous Nations whose existence predates the establishment of the United States, but as individuals untethered and unprotected from tribal governments. And that could be catastrophic for native nations. I hope I am wrong, but nothing in Kavanaugh’s most recent ruling makes me hopeful for the future.

akes Ball’s approach novel is his use of the unpublished writings and correspondence of several Supreme Court justices whose papers are public: Harry Blackmun, Thurgood Marshall, William J. Brennan, William O. Douglas, Hugo Black, and Earl Warren. There are, of course, other justices whose writings Ball might have examined, and the papers of Warren Burger and William Rehnquist, arguably the most consistently anti-Indian voice on the Court, are not open to the public. Despite these limitations, Ball avoids the approach of too many legal works in analyzing decision after decision, and his work in the legal literature is outstanding. Your students who are interested in this subject will benefit from reading Ball’s footnotes.

akes Ball’s approach novel is his use of the unpublished writings and correspondence of several Supreme Court justices whose papers are public: Harry Blackmun, Thurgood Marshall, William J. Brennan, William O. Douglas, Hugo Black, and Earl Warren. There are, of course, other justices whose writings Ball might have examined, and the papers of Warren Burger and William Rehnquist, arguably the most consistently anti-Indian voice on the Court, are not open to the public. Despite these limitations, Ball avoids the approach of too many legal works in analyzing decision after decision, and his work in the legal literature is outstanding. Your students who are interested in this subject will benefit from reading Ball’s footnotes.