On April 2, Angus Laborgne, a resident of the Haudenosaunee reservation at Akwesasne, was cited by New York Department of Environmental Conservation officers for spearing walleyes in Scriba Creek, near a state fish hatchery. The officers cited Laborgne for taking fish out of season, by “means other than angling,” and from what the state considered “closed waters.” Laborgne had speared twenty-three walleyes, all of which the DEC officers confiscated.

Steve Featherstone’s great reporting on NewYorkUpstate.com, and a friend who regularly keeps abreast of the news in Central New York, brought this story to my attention.

Laborgne’s action, according to John Harmon, the President of the Oneida Lake Association, was a “deliberate provocation.”

Three days later, Laborgne returned, accompanied by fourteen other Haudenosaunee fishermen, “from every single reservation.” They speared even more fish from the same waters. The DEC this time decided to stand down, hoping to deescalate what Featherstone described as “a conflict over a complicated legal gray area involving Native American fishing rights under state law—a long simmering fight that made it as far as the governor’s desk last year.”

Featherstone is referring to a bill vetoed by Governor Kathy Hochul that would have recognized Native Americans’ treaty-guaranteed right to be free from state and local fishing laws except for those cases in which the survival of the species was in question. The DEC implied that Laborgne’s fishing did just that. In a statement the DEC noted that “walleyes are concentrating in certain streams,” and are “vulnerable to over harvest” during spawning season. The DEC claim that it “recognized the importance of walleye as a subsistence and cultural resource for Indigenous nations, and is actively consulting with the leadership of the nine State-Recognized Indigenous Nations to advance our shared conservation objectives.”

Fair enough, but it is worth looking at Laborgne’s argument about his rights to fish, and whether the issue really is as complicated as Featherstone’s reporting suggests.

Mr. Laborgne told Featherstone that “according to what I understand, we have the right to all creeks, and all lakes, and all rivers.” The Haudenosaunee, he continued, are born with this right. He said that he planned to return to Scriba Creek, and he would continue to do so until the State of New York recognized “that this is our inherited right…and we have the right. They didn’t give it to us.”

Laborgne is right.

In order for me to show you how, I will have to persuade you to accept some principles that have long been fundamental to the entire field of American Indian law. First, Native American tribes can do whatever they want unless that activity is specifically prohibited by a treaty or an act of Congress. Second, in 1978, Supreme Court Justice William Rehnquist started messing around with this, adding to the principle of “explicit divestiture,” described above, the idea of “implicit divestiture”: Tribes could not exercise those powers that were somehow inconsistent with their status as “domestic dependent nations,” a concept coined by Chief Justice John Marshal 147 years earlier in the case of Cherokee Nation v. Georgia. Tribes, the logic goes, do not give up their sovereign rights as nations that predated the United States unless they do so explicitly. If they did not give away the right or power in question, and if it is not inconsistent with their status as domestic dependent nations, then that power they still possess.

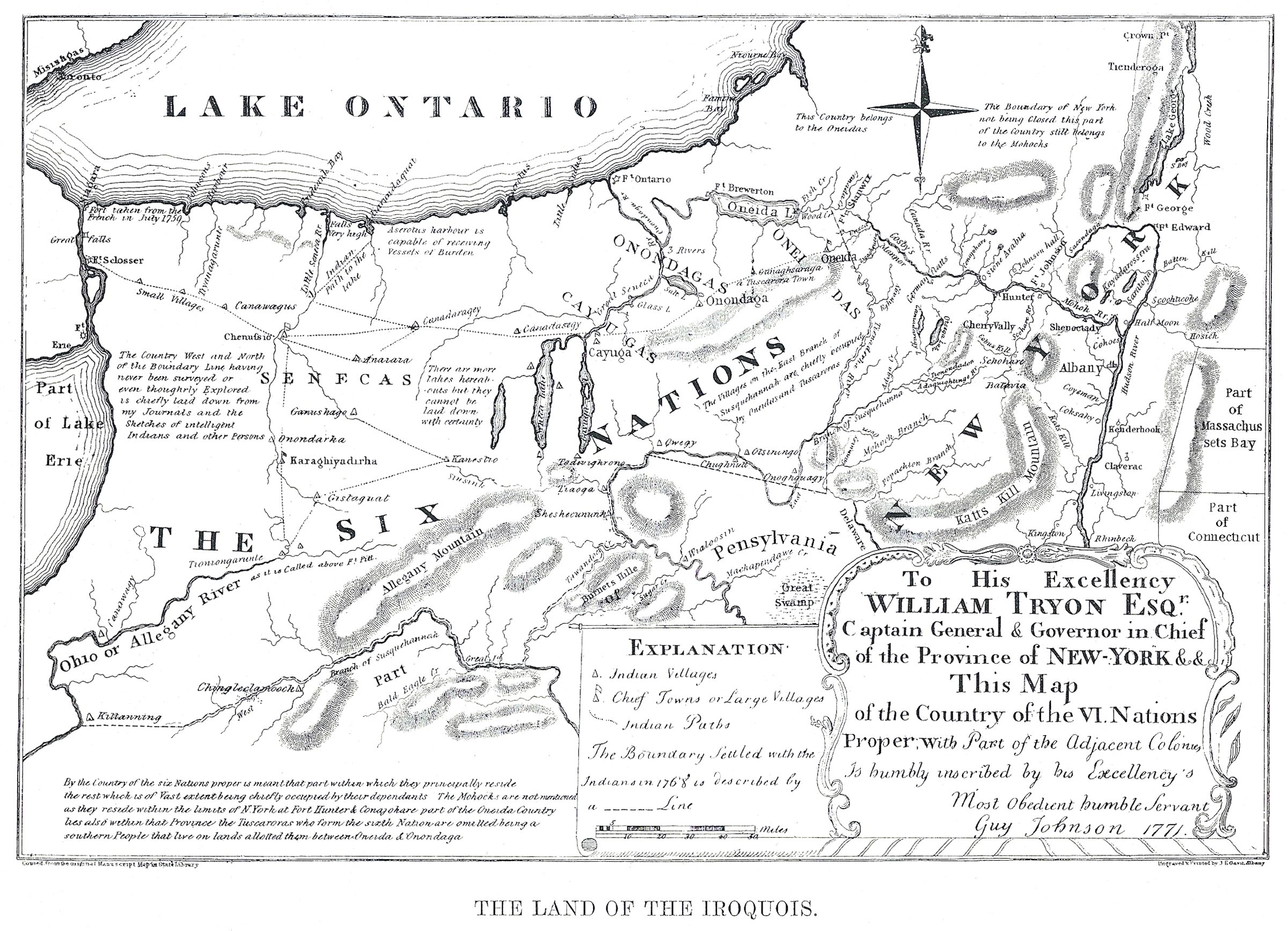

There are a couple of more assumptions I need you to agree to before we move on. Before Europeans arrived in North America, Native American communities had the absolute right to hunt and fish wherever they chose. Thus, unless they specifically gave up that right, through some treaty or some act of Congress, they are still permitted to fish wherever they want.

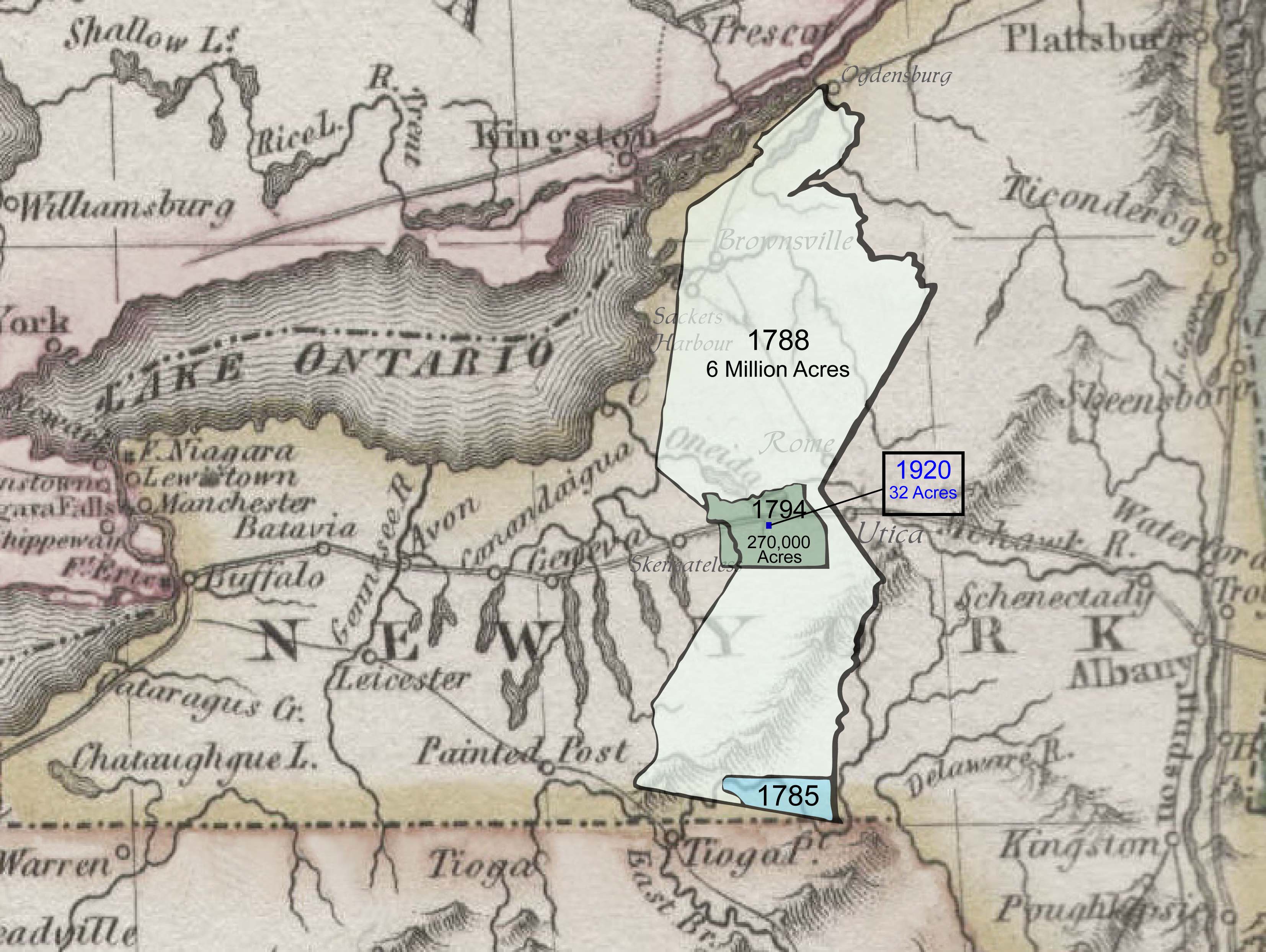

So let’s talk about the treaties the state and the federal government entered into with the Oneida Indians in New York. The 1784 Treaty of Fort Stanwix protected Oneida land from encroachment, an acknowledgment by the United States of the Oneidas’ assistance in the Patriots’ cause during the American Revolution. In 1785 the state of New York coerced the Oneidas into giving up some of their reserved lands, and in 1788 the state came back for more. The 1788 Treaty is the most important one for our purposes, and we need to talk about it.

First, it is worth exploring how the state went about planning for and negotiating this treaty. I am going to spend some time on this because it is so important. I hope you will bear with me.

It seems reasonably fair to conclude that by 1788, the year in which he met with the Onondagas and Oneidas in New York’s Indian territory, Governor Clinton must have recognized that he presided over a state only nominally under his control. British troops continued to garrison forts at Oswego and Niagara, despite the provisions of the Treaty of Paris that had formally ended the Revolutionary War in 1783. These soldiers would not leave New York until 1795, after Jay’s Treaty had been approved. During the war, two of the eastern counties of the state and part of a third seceded, becoming in the process the independent republic of Vermont. Talk of other parts of the state breaking away occurred commonly enough for James Duane to fear that west of the Hudson “a second Vermont may spring up.” Though the punitive Treaty of Fort Stanwix extinguished Iroquois claims to lands largely to the west of New York, much of the territory in the Empire State remained firmly in Indian hands. Clinton needed those lands for his state. As historian Barbara Graymont pointed, Clinton and his colleagues pursued a three-fold program: They hoped to eliminate “any claim of the United States Congress to sovereignty over Indian affairs in the State of New York”; they wanted to extinguish “the title of the Indians to the soil”; and they were determined to eradicate the sovereign status of the Six Nations.

Doing so would not be an easy task, for New York State was not alone in trying to acquire the lands of the Six Nations. Massachusetts claimed much of the land in what is now New York owing to its colonial charter, which specified no western boundary to its territorial limits. The two states had worked out a compromise at Hartford late in 1786, with the result that New York exercised legal jurisdiction over the lands in question, but the Bay State retained the right of preemption, or first purchase, to Indian lands in upstate New York. Massachusetts promptly sold these preemption rights to two speculators, Oliver Phelps and Nathaniel Gorham who, in July of 1788, concluded a treaty with the refugee Mohawks, Oneidas, Onondagas, Cayugas and Senecas at Buffalo Creek. Phelps and Gorham acquired nearly 2.6 million acres of Iroquois land in western New York for five thousand dollars and the payment of an annuity to the Indians of five hundred dollars.

In addition to the problems posed by the Phelps-Gorham purchase, Clinton and his associates worried about the activities of the New York Genesee Company of Adventurers, a wealthy and influential group of land barons led by John Livingston. On the 13th of November, 1787, the Livingston Company negotiated a lease with “the Chiefs and Sachems of the Six Nations of Indians.” The sachems “leased” to the Livingston Company, for a term of 999 years, “all that certain Tract or Parcel of Land, commonly called and known by the Name of the Lands of the six Nations of Indians, situate, lying and being in the State of New York, and now in the actual possession of the said Chiefs and Sachems of the Six Nations.” Livingston and his associates agreed to pay to the sachems “the yearly Rent or Sum of Two Thousand Spanish Milled Dollars, in and upon the fourth Day of July.” Two months later, the Company negotiated an additional lease with the Oneidas, “for the said term of nine hundred and ninety-nine years, on a rent reserved for the first year of twelve hundred dollars per annum, until it shall amount to fifteen hundred dollars, of all those lands in the said writing described, as the Tract of Land commonly called and known by the Territory of the Oneida Indians.”

Early in 1788, Governor Clinton and his associates in the State Assembly and Senate undertook a concerted campaign to consolidate their control over the conduct of Indian policy in New York and the disposition of those lands the Iroquois could be persuaded to part with. Clinton and other New Yorkers wanted to acquire Iroquois lands for the settlement of the state’s obligations to its revolutionary war veterans. Without question paying off the state’s obligations to its soldiers was important to Clinton, but as historian Laurence Hauptman has shown, other factors were important as well. The consolidation of state control over its western lands, the development of the state’s economy, and the construction of a state wide transportation system all relied upon New Yorkers first acquiring title to Iroquois lands. The Six Nations were in the way.

Early in 1788 the New York State Assembly invalidated the Genesee Company of Adventurers’ “leases” of Six Nations land. According to a joint resolution approved by the State Senate and Assembly, the leases, by their terms, were for all intents and purposes “purchases of lands, and . . . by the constitution of this State, the said leases are not binding on the said Indians, and are not valid.” They determined that “the force of the State, shall from time to time, as occasion may require, be exerted to prevent intrusions on and for preserving to the people of this state, their rights to the lands and territories comprehended within the boundaries specified in the said leases.”

To prevent problems like that presented by the Genesee Company of Adventurers for the future, the Assembly and Senate on the 26th of February enacted a law “for directing the manner of proving deeds and conveyances to be recorded.” For a purchase of lands to be valid under New York state law, that purchase must be witnessed and recorded and proved “by one or more of the subscribing witnesses to the same, before one of the justices of the supreme court, or a master in chancery, or one of the judges of the court of common pleas in and for the county where such lands and real estate are situated.” Through this enactment, the state tightened its control over the procedures through which land changed hands. Furthermore, the Legislature on the 18th of March approved a law “to punish infractions of that article of the Constitution of this State, prohibiting purchases of lands from the Indians, without the authority and consent of the legislature; and more effectually to provide against intrusions on the unappropriated lands of this State.” No purchases of land from Indians, “within the limits of this State, shall be binding on the said Indians, or deemed valid, unless made under the authority, and with the consent of the Legislature of this State.” Any person who acted without the permission of the Legislature would pay a fine of 100 pounds to the people of New York, “and shall be further punished by fine and imprisonment in the discretion of the court.”

After taking these steps to ensure that no unauthorized parties acquired Indian lands within the state, and after depriving the New York Genesee Company of its ill-gotten gains, Clinton and his allies in the Legislature appointed commissioners to negotiate treaties with the Six Nations. There is, contrary to the claims of the defendants’ experts, no evidence they present that demonstrates that the Iroquois knew that the New York State Legislature had invalidated the Livingston Leases and nothing Clinton or the state commissioners told the Onondagas and Oneidas in the summer of 1788 could have led them to that conclusion.

At Fort Schuyler, the governor and the state’s Indian commissioners continuously warned the Indians that their lands remained in jeopardy unless they negotiated with the state. The governor accompanied the state commissioners to Fort Schuyler, formerly Fort Stanwix, where they would meet with as many Indians as could be gathered. The Six Nations, the governor hoped, would “open their ears to the voice of the Great Council of the State of New York,” and meet them to “brighten the Chain and renew the Covenant which had so long bound us together.” Clinton and the commissioners informed the Iroquois that they intended to protect the Indians from the many outside forces that clamored for their land. Deceptively, the governor and the commissioners hoped to exploit the confusion then reigning in Iroquoia, and obtain from the Six Nations an enormous cession of Indian lands.

Governor Clinton appears to have wanted to move quickly. He attempted to rush the proceedings. He informed the Onondaga sachems, for instance, that “the other public business of the State will not permit me to remain long from home and it will therefore be necessary for such of your people as propose to bee at the Treaty to come on with all possible haste or they may be too late.” Though there is no evidence that the Iroquois sachems clearly recognized, understood, or cared about the nature of that “public business,” Clinton indeed had plenty to worry about. New Yorkers overwhelmingly had opposed the new Federal Constitution drawn up at the convention held in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787, and the governor (albeit quietly) led the “Antifederalist” forces within his state. Advocates of a stronger national government felt the need to replace the Articles of Confederation for a number of reasons, but the “father of the Constitution,” James Madison, listed high on his list of “Vices of the Political System of the United States” the aggressive Indian policies pursued by several of the states, including New York. Article I, Section 8, of the new Constitution replaced the vague and ambiguous language of Article IX of the Articles of Confederation, with an assertive statement of federal authority over the conduct of Indian affairs: once the Constitution became the “supreme law of the land,” Congress would possess the exclusive authority “to regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes.”

New Yorkers had ratified the new constitution, reluctantly, in July, only a few short months before the gathering at Fort Schuyler. When word of the Constitution’s ratification in New Hampshire and Virginia arrived earlier that month, the Antifederalists of New York realized that they no longer could safely oppose the Constitution: the United States would exist under a new and more powerful frame of government. The question posed to the delegates at Poughkeepsie was now no longer whether or not New Yorkers would approve the Constitution, but whether or not they would become a member of the Union now that the requisite number of states had ratified. Complete independence was never considered by New York’s Antifederalists, who recognized that they would soon have to work within the new federal system. Governor Clinton must have felt the need to acquire for New York as much of the Iroquois estate as he could before the new government went into effect, and the rules of Indian diplomacy changed.

New York’s urgent appeal to the Six Nations was received by a people still recovering from the ravages of the Revolutionary War. Although the Oneidas suffered comparatively less than their brothers in the Confederacy, they may have been confused or concerned about Governor Clinton’s intentions. Certainly representatives of the Genesee Company of Adventurers tried to disrupt the proceedings at Fort Schuyler. A Seneca named Onyegat told New York’s Indian commissioners that men from the Genesee Company had told him that “the Governor’s Business at this proposed Treaty is to purchase your Lands, but you have leased them to us. He means to pay you all at once for them, and then in a few Years to drive you off and tell you that you have no Property here.” A Frenchman named Dominique Debarges, a fur trader from Montreal and a Genesee Company agent, along with an Indian named “the Infant,” told sachems on their way to Fort Schuyler that “it will be your Destruction if you go down to the Treaty called by the Governor of New York. I know his intentions,” Debarges continued, and “when you return you’ll have no Place to set your Foot on. You will be like wild beasts which are hunted.” Debarges also told the Indians that “the Governor had his troops collected at German Flatts, ready to fall upon them as soon as they returned.” The Oneidas, as well as the Onondagas, likely heard these rumors; the evidence suggests that the constituent members of the Confederacy regularly shared information and intelligence. That the missionary Samuel Kirkland served as an interpreter at Fort Schuyler could only have further confused the Indians attending the council. The minister and missionary had served as an interpreter at the federal Fort Stanwix Treaty in 1784, and his presence at Fort Schuyler may have done much to grant a veneer of legitimacy to Clinton’s efforts and supported the Governor’s contested claim to represent the only jurisdiction with a legitimate right to negotiate with the Six Nations.

The state commissioners chose to treat with the Onondagas first. The Oneidas returned home, and would not return to Fort Schuyler until the meeting with the Onondagas had been completed. By the middle of September, that business was finished, and the Oneidas returned to the fort.

Speaking through Kirkland, the Oneida spokesman Good Peter responded to the Commissioners’ invitation. He expressed to the Governor and the state’s men his understanding of the purpose of the gathering. Good Peter wanted to protect the Oneidas’ lands. He made clear to Governor Clinton that “in whatever Land we should cede to you, our Warriors should have the Privilege of Hunting and Fishing, and that a Line should be drawn round the Part we should reserve to ourselves to secure it to us and our Posterity.” In essence, Good Peter, like the Onondaga sachem Black Cap, offered to share the bulk of the Oneidas’ lands with the citizens of the state of New York in return for an annual payment. The remainder of their lands the tribe would keep for their own exclusive use.

Governor Clinton told the Oneidas that he desired to protect their lands from the Livingston Adventurers, who “had without any Authority from us, obtained from you a Lease of your Lands.” He had, he said, no interest in buying lands from the Oneidas, for “we have already more lands than we have People to settle on them.” His hope was to set things right, “to meet you at this Council Fire, and by a new agreement place Matters on such a footing as to prevent these Things for the future.” This pleased Good Peter, who responded to the Governor’s speech on the 20th of September. He was happy to hear that the state did not want the Oneidas’ land, and that New York would protect his people from the Livingston Company. “The Wind,” he told Clinton, “seems always to blow and shake this beloved Tree, this Tree of Peace.” Good Peter recalled that in 1784 “the United States” had “Planted the Tree of Peace with four Roots, spreading branches, and beautiful leaves, whose top reached the Heavens.” He feared “that by and by some Twig of this beautiful Tree will be broken off. I Love this Tree of Peace as my Life, and my Protection. I know you love it.” To preserve this peace, Good Peter concluded, the Governor must “punish these disorderly People.”

The point is simple. Throughout his speeches at Fort Schuyler that September, and consistently in his recollections of the treaty four years later, Good Peter believed whole-heartedly that the Oneidas had met with the governor and the state’s Indian commissioners to protect his people from dispossession by the Livingston Company. Indeed, at the close of the council, Good Peter proudly announced to Governor Clinton that “My Nation are now restored to a possession of their Property which they were in danger of having lost.” The 1788 Oneida treaty, Good Peter continued, secured to the Oneidas “so much of our Property which would otherwise have been lost.” Clearly Good Peter would have had no reason to make this statement if he knew, prior to the meeting at Fort Schuyler, that the Livingston leases had been invalidated by the State Legislature.

Here’s something else that treaty did. Even though the deceptive treaty read that the “Oneidas do cede and grant all their lands to the people of the State of New York forever,” with the exception of a small reservation, they reserved for themselves “and their posterity forever…the free right of hunting in every part of the said ceded lands, and of fishing in all the waters within the same.” The Oneidas reserved the right to hunt and fish in all the lands they ostensibly had ceded to the state of New York.

The 1794 Federal treaty of Canandaigua guaranteed the Oneidas and their longhouse kin the right to the “free use and enjoyment” of all their lands. Nothing in that federal treaty deprived them of the reserved fishing rights laid out at the 1788 Fort Schuyler treaty. Nor did any of the numerous land cessions signed by Oneidas in the decades that followed 1788. Not one of these agreements deprived the Oneidas of the right to fish in streams and lakes they ceded to the state in 1788. Those rights remain active still.

Of course the DEC has an interest in preserving walleye, and it is good that the Department recognizes that Haudenosaunee people do. There is reason to hope that this issue might be compromised. But until that compromise takes place—and Governor Hochul’s hostility to the state’s Indigenous peoples leaves me feeling uncertain that it ever will take place—Native Americans are free to exercise the rights guaranteed in their treaties. They are not asking for special privileges. Rather, they are asking that the State of New York honor its word. When it comes to Native Americans, perhaps the time for the state to finally start doing that is now.