In a speech delivered last week before the United Nations, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau spoke about his country’s history of relations with its indigenous population. He wanted to show the world that Canada could take responsibility for the “terrible mistakes” of its past.

Whether or not Canada has succeeded in doing, so, Trudeau spoke of the enduring legacies of colonialism. “Early colonial relationships,” he said, for Canada’s First Nations, Metis, and Inuit peoples, “were not about strength through diversity, or a celebration of differences,” but rather an experience that “was mostly one of humiliation, neglect, and abuse.”

And the damage has been long-lasting indeed. Trudeau spoke of Canadian indigenous communities with unsafe drinking water, of large numbers of missing or murdered indigenous women. He spoke of “Indigenous parents in Canada who say goodnight to their children, and have to cross their fingers in the hopes that their kids won’t run away or take their own lives in the night.” The problems of which Trudeau spoke have been well-documented.

Trudeau has faced significant criticism at home from indigenous spokespeople w ho feel that his words have not been matched by action. Many have criticized the Canadian movement towards reconciliation, which I have written about on this blog, as a feel-good movement for white people that does nothing about structural inequalities and injustices deeply rooted in Canadian society. These are significant critiques, and it is well-worthwhile for students of America’s native peoples to watch how Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission continues its work. (You can access its reports here.)

ho feel that his words have not been matched by action. Many have criticized the Canadian movement towards reconciliation, which I have written about on this blog, as a feel-good movement for white people that does nothing about structural inequalities and injustices deeply rooted in Canadian society. These are significant critiques, and it is well-worthwhile for students of America’s native peoples to watch how Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission continues its work. (You can access its reports here.)

But despite the criticism of Trudeau and the limitations of his approach, for an American president to even consider saying something close to what Prime Minister said before the UN is utterly inconceivable. If you saw the excellent “Wind River,” you will recognize that the problem of missing and murdered indigenous women is not exclusive to Canada. Corporate profit-seeking in Indian Country has led to the devastation of water supplies on American reservations. I have written much on this blog about DAPL (the documentary “Awake: A Dream from Standing Rock” is strong on sentiment but weaker in terms of substance) but that is hardly the only example. More than a third of all Superfund sites are located in Indian Country, and others, like Onondaga Lake in Syracuse, are nearby. Police violence against native peoples, disproportionate rates of incarceration, and higher rates of deficiency on every measure of social well-being: the problems are enormous, the challenges daunting, and the resources available limited. In both Canada and the United States, these are the legacies of an enduring colonialism.

Now, if I were to ask my students if they should expect President Trump to deliver a speech similar to that given by Prime Minister Trudeau, they would emphatically say “no.” If I were to ask them why, their answers would be a bit more complex. For to assert that Trump is a racist or white supremacist uninterested in hearing about complaints from or the conditions experienced by peoples of color, while true, only gets us so far. No American president, whatever his party, has spoken as frankly as Trudeau about his country’s mistakes and misdeeds. No, there is much more to it than the current American president’s long list of shortcomings, inadequacies, and character flaws.

The United States, regardless of its leader, has shown little interest in confronting its long history of colonialism. The growth of the United States could not have occurred without the wholesale and systematic dispossession of native peoples. Sure, many of the thousands of transactions where Indian land came into the hands of white people were “legal” in the sense that they were recorded in deeds or ratified in treaties, but these transactions have histories of their own. They occurred because of the relentless pressure exerted by European farmers and their livestock on native lands, or because native peoples decided to sell lands that they knew from hard experience “settlers” would take from them anyways, or after epidemic diseases reduced an indigenous community’s population and this made their lands seem “vacant” or as “surplus” land. Some of these cessions were the price of peace after a military invasion of conquest and desolati on. Dispossession and violence often walked hand-in-hand.

on. Dispossession and violence often walked hand-in-hand.

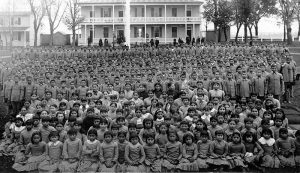

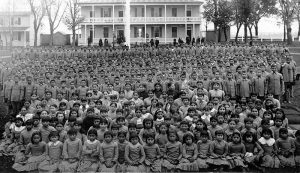

The loss of land was immense. But it cannot be understood apart from the assault on native peoples’ cultures and ways of living. Just as Canada had its residential schools, the United States had boarding schools. Still, there was so much more to the assault on Indian identity, and it was so much more thorough than a focus on these sadistic institutions might lead one to believe. I tell the story of this cultural assault in Chapter 8 of Native America.

We,  as a country, are not very good at talking about our misdeeds. We insulate our children from these stories, for instance, for a variety of reasons: because the stories of the suffering that his country has caused native peoples are so massive that kids could not handle them, or because somehow hiding the country’s crimes from them is the best way to produce loyal and patriotic citizens. So we design curricula that talk about tiny parts of the Native American past, but not in a way that would cause children to question their country’s conduct. It happened a long time ago. We are free and clear, we tell them. We’ll blame it on Andrew Jackson, and call it a day.

as a country, are not very good at talking about our misdeeds. We insulate our children from these stories, for instance, for a variety of reasons: because the stories of the suffering that his country has caused native peoples are so massive that kids could not handle them, or because somehow hiding the country’s crimes from them is the best way to produce loyal and patriotic citizens. So we design curricula that talk about tiny parts of the Native American past, but not in a way that would cause children to question their country’s conduct. It happened a long time ago. We are free and clear, we tell them. We’ll blame it on Andrew Jackson, and call it a day.

Meanwhile we cast Indians as part of the past, a point I have raised on this blog many times, because it makes it easier to deny their just grievances today. We will pat ourselves on the back for renaming a football team, or changing Columbus Day to “Indigenous Peoples Day,” or persuading this or that religious denomination to renounce its approval for the Doctrine of Discovery, valuable though these acts may be. But let’s be clear. These actions cost white people little, and the structural burdens imposed by colonialism and white supremacy survive them and remain intact. We like to tinker around the edges of significant problems. Too many of us view manifestations of Indian identity as inauthentic, and the expressions of long-held grievances as belly-aching about things that happened long ago. We do not believe, as a rule, that inter-generational trauma is a thing, or that the burdens of history weigh more heavily upon some people than upon others.

We are unrepentant, unwilling to apologize, and to many of us too ill-informed or too uninterested to learn and understand how Native America’s loss has been white America’s gain.

As I wrote the first draft of this post earlier this morning, the hourly NPR newsbreak came over the radio. The first story was Donald Trump’s denunciation of those NFL players who, with respect and civility, took a knee to protest police brutality and the continuing slaughter of people of color by the nation’s law enforcement officers. The second story involved the shooting of a deaf person of color by police officers in Oklahoma. The victim did not hear the officers’ demand that he set down the metal pipe he was holding.

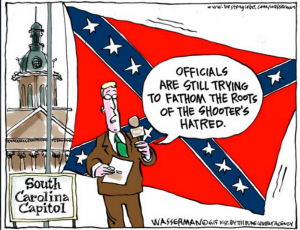

This country, it’s something else sometimes. As native peoples long have told us, white people in America are comfortable dictating to people of color how they should conduct themselves, the forms of grievance and redress-seeking that are legitimate, not to mention how to conduct themselves religiously, spiritually, emotionally, sexually, domestically, and aesthetically. When kneeling for the National Anthem is viewed as more disrespectful than flying the Confederate flag, and when this proposition can be debated, defended, and taken seriously by millions of almost exclusively white Americans who support the President, it is pretty evident that the sickness is rooted deep.

Justin Trudeau clearly has not come close to doing what his very sincere and committed critics want him to do, but he has done more than any American president, and he is light years ahead of our Brass Creon. Talking cannot do everything, and acknowledging past crimes is not a remedy by itself. But it’s a start. It is a vital precondition to things getting better. The act of acknowledging that I am at least partially responsible for your pain, and that I have benefited from the historical suffering of your people: it can be a powerful thing. I am fully aware that I am speaking favorably of Prime Minister Trudeau for doing, at the end of the day, what any informed and honest person would do. Yet our current leadership, in politics and in public education, in the Democratic and in the Republican parties, are not even close to being able to clear so low a bar.