“Civilization or Death to all American savages!” That was one of a number of toasts offered by the officers who accompanied James Sullivan’s invasion of Iroquoia during the American Revolutionary War. Planned and plotted by George Washington himself, the “Sullivan Campaign” burned dozens of Haudenosaunee towns, destroyed crops, orchards and fields, and forced the Iroquois to flee from their homelands toward the British post at Niagara. There they suffered and died in large numbers during one of the worst winters on record. In a letter to Lafayette, Washington expressed his hope that the expedition would eliminate the considerable threat hostile Iroquois posed to the rebel movement, “distract and terrify” them, and “extirpate them from the Country.”

I tell the story of the Sullivan Campaign in Native America. You can also read a rather dry, nuts-and-bolts military history that focuses exclusively on the American side in Joseph Fischer’s A Well-Executed Failure. Most recently, Colin Calloway in his fine examination of The Indian World of George Washington covers the expedition in all its brutality, from Van Schaick’s rape and murder of Onondaga women, to the atrocities committed by Sullivan’s men. And it is not just academic historians with an interest in the story. The Empire State Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, with financial backing from the William J. Pomeroy Foundation, has introduced its “Sullivan-Clinton Campaign of 1779 Historic Marker Grant Program.” The ESSSAR ( try saying that without sounding like Kaa) invites you or your organization “to help commemorate the 250th anniversary of the Revolutionary War Sullivan-Clinton Campaign of 1779 by erecting a specially designed Historical Marker.” The Pomeroy Foundation “will provide full funding for the marker, pole, and shipping.” Installation is up to you.

If you want to submit a proposal for a historical marker, your time is running out. The deadline is September 14th. You can fill out the form here.

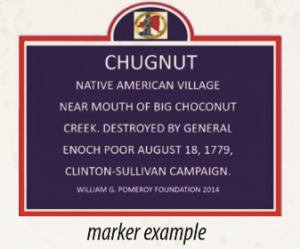

The website includes a small sample marker you might use as a template. “Chugnut,” the sample reads, “Native American village near mouth of Big Choconut Creek destroyed by General Enoch Poor, August 18, 1779, Sullivan-Clinton Campaign.”

If this marker is an indication of things to come, it looks like this will be a history uninformed by the important recent scholarship on native peoples, focusing mostly on what Continental soldiers and officers did with little attention to destroyed towns and and shattered lives, the uprooting of a people and their transformation into refugees, and the atrocities committed against non-combatants. Chugnut is there, but then it is not. No sense of what it was before, or what became of the people who lived there. No sense that the rise of New York as the Empire State could not have occurred without war and violence, and without a systematic campaign of dispossession carried out by the state against the Haudenosaunee.

The ESSSAR campaign information came to me during the summer. To some extent, I am still catching up with some of that email. I do not have time, regrettably, to submit a proposal for signs. That is my fault. I would very much like to send a large number of suggestions. I get that I am too late.

But I hope the sponsors of this project will seek out Haudenosaunee voices and solicit their suggestions for marking the path carved by Sullivan’s men, and measuring the destruction it wrought. The Sullivan Campaign was designed expressly to eliminate the Iroquois as a force in the western reaches of what came to be New York State. The Americans wanted to erase their towns, destroy their food supplies, force them from their country, and drive them to starvation over the winter outside of Fort Niagara. You might call this an invasion. You might say this was war. But you could also call it ethnic cleansing. Or genocide.

There is that tired cliché: The winners write history. Might makes write. Well, yes, they do, but it is usually not very good and it is almost always incomplete. If you have used Native America, or if you have managed to keep abreast of the massive literature in Native American Studies written by anthropologist, archaeologists, and historians, you will note that there are a wealth of sources that can be used to reconstruct native experiences during the Revolution. You can ignore them if you want when you commemorate acts of war, but we historians have a name for that, and we will judge you harshly if you do so. We will judge you in the same way we judge those who continue to defend the racist monuments celebrating the Confederacy erected after the Civil War. Like them, you will be encouraging a history of erasure, one that conceals the misdeeds of the past, and obscures the sufferings of those who became the victims of history. Good historians remember and understand that what some people choose to “commemorate,” others are compelled to mourn.