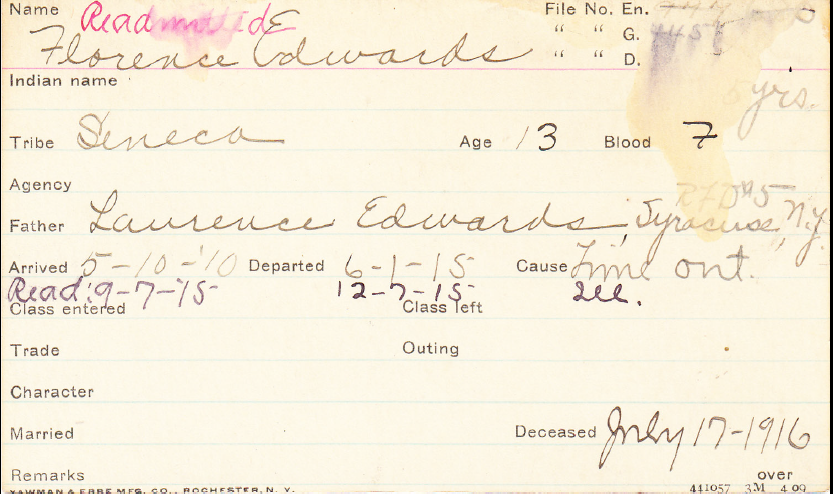

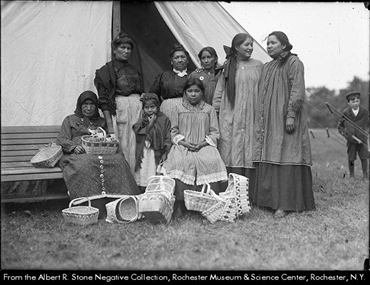

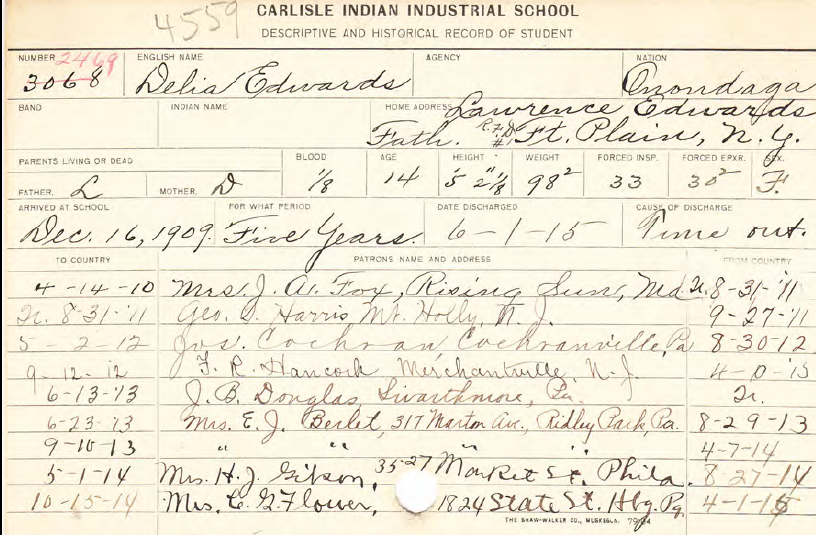

THEY WERE JUST KIDS. That is something that leaps off the page when you look at their student files. Delia and Florence Edwards, two Onondaga sisters, arrived at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in December of 1909 and May of 1910, respectively. Delia was fourteen years old, Florence 13.

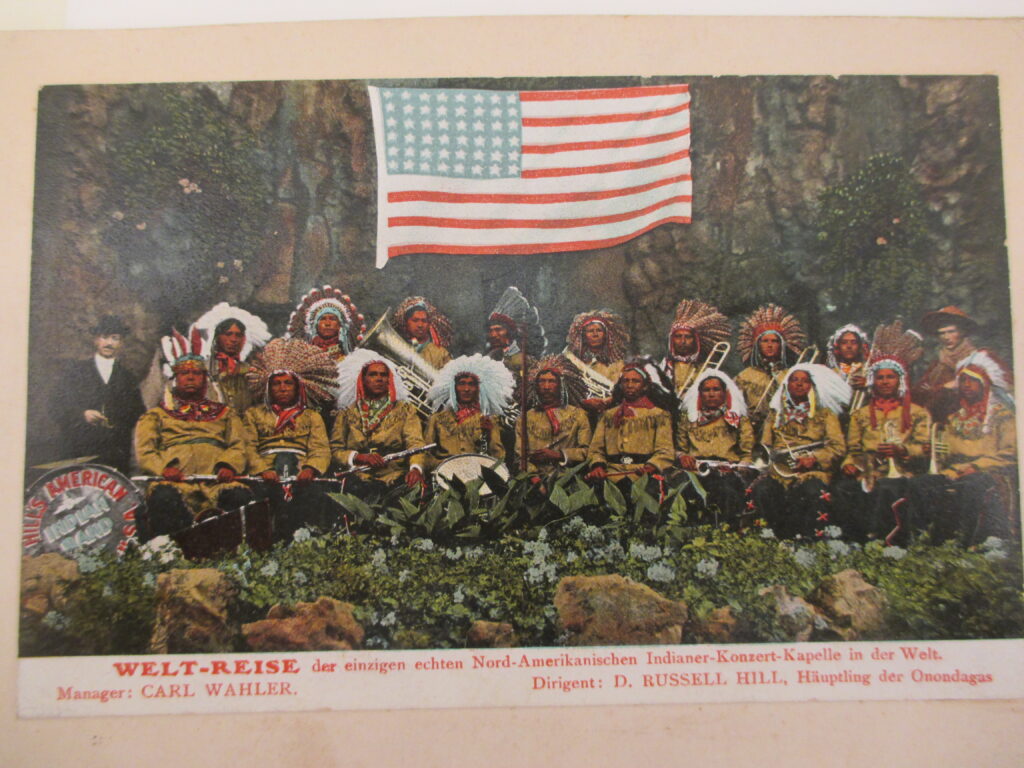

They were not dragged to Carlisle. State officials did not forcefully remove them from their homes. Like many of the young people who came to Carlisle, a parent signed them up. The girls attended the Onondaga Nation School for a couple of years, and then the Mindenville School District in the Mohawk Valley before they came to Carlisle. By the time the girls arrived, Carlisle required all students to have had several years of prior schooling and fluency in English. David Russel Hill, an Onondaga chief, the leader of the Onondaga Indian Band, and an advocate for Indian education, wrote on both of the girls’ applications that they had “advanced beyond the required studies.” If they wished to continue their schooling, he suggested, Carlisle may have been the best and the only opportunity open to them.

RECENT MONTHS have witnessed the discovery of more than 1300 unmarked graves at the site of a number of Canadian residential schools. The discoveries, according to a story that ran in the Ottawa Citizen, are proof of what First Nations people have been saying for a long time: “That Canada’s Indian Residential Schools spent nearly a century overseeing shockingly high rates of death among their students, with the bodies of the dead routinely withheld from their families and home communities.” In part because of the outcry these discoveries sparked, the American Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland announced an initiative to “address the inter-generational impact of Indian boarding schools to shed light on the unspoken traumas of the past, no matter how hard it will be.” Haaland cautioned that the work would be difficult and time-consuming. Nothing, she said, will “undo the heartbreak and loss we feel.” Nonetheless, she said, “only by acknowledging the past can we work toward a future that we’re all proud of.”

The Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative will investigate “the loss of human life and the lasting consequences of residential Indian boarding schools.” These schools, said Bryan Newland, the Principal Deputy Assistant for Indian Affairs, were intended to “culturally assimilate Indigenous children by forcibly relocating them from their families and communities to distant residential facilities where their American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian identities, languages, and beliefs were to be forcibly suppressed.” “Hundreds of thousands” of Indian children, Newland said, were taken from their communities. The Interior Department will work to collect the relevant documents, locate possible burial sites, and try to set the record straight.”

This is a worthwhile project, one of the only times in American history where an agency of the federal government has pledged to take an honest look at its history, collect the evidence, and allow for a true accounting of this part of the nation’s past. It is stunning, really. Having spent much of my work time the last year or so reading through Carlisle student files, this will be complicated and in many ways difficult work. And it may force many people to reconsider what they know to be true about Indian boarding schools.

CARLISLE WAS ABOUT 250 MILES south of the Onondaga Nation Territory, so Delia and Florence traveled less far than most of the 10,000 students who attended the school between 1879, when it opened, and 1918, when it closed.

It is difficult to discern much about the girls’ lives before Carlisle. Their Onondaga mother had died from heart disease, and they were being raised by their Mohawk father on the Nation Territory. We know which schools they attended, and that they were Protestants, though the denomination is not clear.

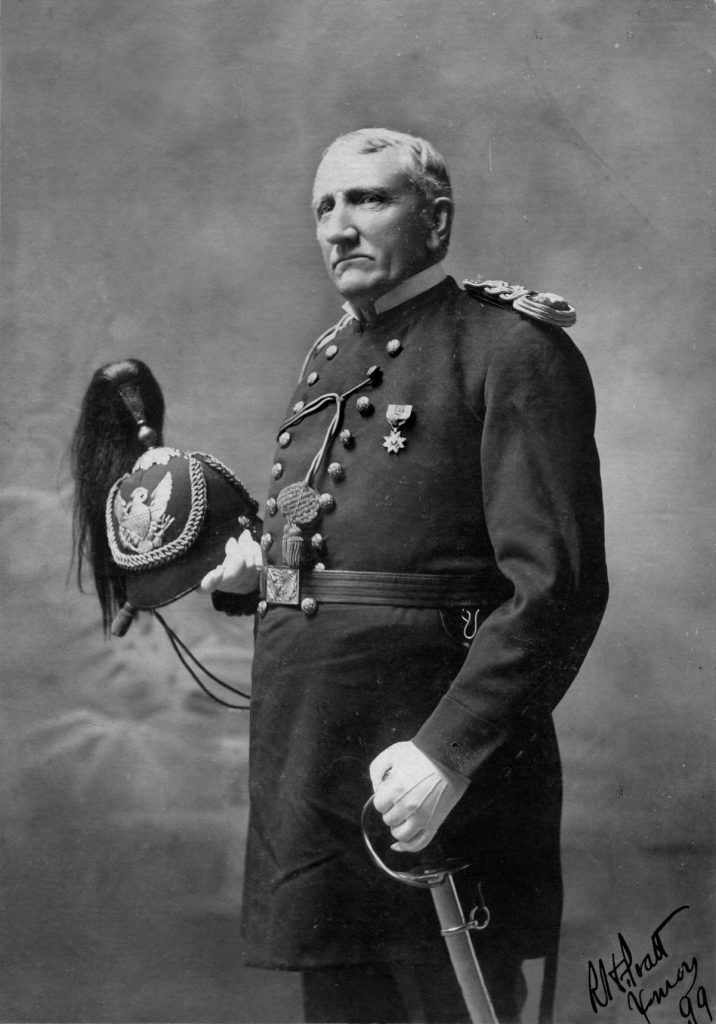

A military officer named Richard Henry Pratt founded the school to “kill the Indians and save the man.” Speaking to a gathering of Baptist ministers in 1883, Pratt said that “in Indian Civilization, I am a Baptist, because I believe in immersing the Indians in our civilization and when we get them under holding them until they are thoroughly soaked.” The best that Pratt could see in the thousands of young Native Americans who attended Carlisle was that with proper training they might be formed into something else, and he boasted of his ability to do just that.

Pratt was an energetic and effective promoter of the school. He produced before and after photographs of Carlisle students, the first depicting the child in their traditional dress, the second with their hair cut, their faces cleaned, and dressed in Carlisle’s school uniform. Pratt claimed that Carlisle took “savage” and “wild” Indians and transformed them into civilized individuals, ready for citizenship and productive employment in the American republic. His school, according to a newspaper article announcing its opening, “will endeavor to save the Indians from extermination by educating young Indians, who can grow up to be leaders of their people and direct them to civilization.” In reality, the largest numbers of students came from Iroquois communities, eastern Cherokees, and the Oneidas in Wisconsin. These young people spoke and wrote in English when they arrived, were members of Christian denominations, and familiar with farming.

Pratt needed to promote his efforts. Contrary to popular belief, policy-makers began to criticize off-reservation boarding schools as educational institutions. Early twentieth century commissioners of Indian Affairs and secretaries of the interior, for instance, much preferred reservation day schools, which were less expensive because they allowed children to return home at the end of the day, and because they better prepared the students for life in American society. Francis Leupp, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, wrote in 1905 that “it is a great mistake to try, as many good persons of bad judgment have tried, to start the little ones in the path of civilization by snapping all the ties of affection between them and their parents, and teaching them to despise the aged and nonprogressive members of their families.” Pratt retired five years before the Edwards sisters arrived, at a time when boarding schools faced a steady drumbeat of criticism from reformers, political leaders, and of course Native peoples themselves, who viewed them as retrograde institutions, dated and of questionable value compared to the benefits of schools closer to home.

Students at Carlisle spent only some of their time on school grounds. Much of their time was spent on their various “Outing” placements, where they were sent to live with white families to learn a craft or a trade or, in the case of women, basic housewifery. If they were old enough, they attended schools near their patrons’ home. Delia attended Moorestown High School in New Jersey, and Florence attended Haddonfield High.

Delia’s patrons found her “headstrong and self-willed,” but capable of doing well when she tried. Another thought she was “a great child and tries to please.” Florence spent time in Jenkinstown and Kennet Square, Pennsylvania, and at a couple of sites in New Jersey. One of her patrons, in 1910, told the Carlisle field agent, whose job it was to check in on students, that “Florence is not satisfactory, she is not very strong, is at a critical period in her life.” The thirteen year old was “willing,” but just not capable, in the eyes of her patron, to provide enough help. “She is very untidy about her person & work.” A year later, however, a new patron in Beverley, New Jersey, reported that she was very fond of Florence, and found her “a good obedient child, a little slow, but tries and is improving.”

Florence may have struggled at times during her placements, but she took advantage of the opportunities Carlisle presented. She wrote for the student newspaper. She received a prize for one of her essays from the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. She was an active member of Carlisle’s YWCA chapter, and at one meeting led the students in a lecture on “the heroes of the Bible.” She was also a member of the Mercers, where she practiced “Declamation.” IN 1914, she gave a reading in the auditorium of her essay, “Is it Worth While?” (The paper gave no sense of what “it” was). In January of 1915 she led the Protestant service at the school “and also gave a fine little talk.” She must have been a magnetic figure, filled with charisma. People liked her.

Both of the girls went home for the summer of 1915. By September they were back at school and both had moved on to their next placements. In October of 1915, the Carlisle Arrow ran a report of students staying in the school’s hospital. Florence “who came in from the county,” was one of them. She was “now up,” and, according to Agnes Owl, “was only lonesome for Carlisle.”

Turned out it was much more serious. Florence had contracted tuberculosis, the dread disease that killed 194 out of every 100,000 Americans at the beginning of the twentieth century. Lawrence Edwards, her father, began to hear that his daughter was ill. In November he wrote to the school’s superintendent, asking for information. He had heard nothing from Florence, but “others are telling me she is sick.” Two weeks later, on the sixth of December in 1915, the Superintendent wrote back. Florence was cured, but he told Mr. Edwards that he thought it advisable “to let your daughter…have a complete rest in order that she regain her physical strength.” He was sending her home to Onondaga.

Delia, it turned out, was sick as well. Mrs. Lippincott, one of her patrons, sent Delia to the hospital. She complained of abdominal pain. It was appendicitis, and she had surgery in November. She recovered well. While Florence journeyed home to rest, Delia returned to her patron. She wanted to go back to Carlisle. She wrote to her friend Lucy Lenoir, a Chippewa student. The letters are wonderful. Delia was a relentless kidder, always ready to affectionately tease her friend. And she was bored to tears at times doing housework for her patron. “I wish we could be there for the social which will be the last Saturday” of January. Earlier, she told Lucy, she had broken up with her boyfriend. “We certainly would make a hit on some swell guys,” she wrote. But getting back to Carlisle was more difficult than it should have been. The superintendent saw no reason for her to return to the school. Her patrons reported that her work was good, and that she was succeeding in her studies. Delia told Lucy that “I am so darn sick of country life I believe I’d die if I stay here much longer.” Maybe, she wrote, “I’ll play sick and see if I can’t go back to Carlisle.” She missed her friends. A short time later she wrote to Lucy again, saying “Dearie, I have no idea where I will be when you open this letter, but if I am not in my grave I will be at dear old Carlisle.”

Delia would not make it back to Carlisle until June. In May of 1916, Lawrence wrote to the superintendent. “My daughter Florence is very low now and I wish to have Delia come to her before anything happens.” Delia was summoned back to the school, where she arrived on the First of June. She returned home to the Nation Territory on June 6.

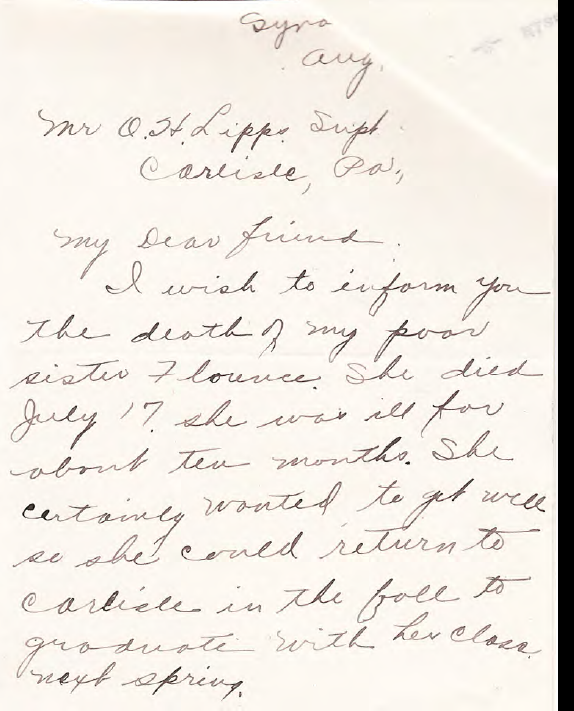

One month later, Florence died. “She had been ill for about ten months,” Delia wrote. “She certainly wanted to get well so she could return to Carlisle in the fall to graduate with her class next spring.” She told the superintendent that it was hard for her to lose a sister. “Father and I are trying our best to bear it,” she wrote, “but life is not ours so we will have to take things as they come.” Her sister had returned to Carlisle from her outing assignment with a fatal illness. The school’s records document the names of the children who died there. Still, Delia could not wait to return. Like many of the Onondagas who attended Carlisle, she missed the school when she was not there. She was nineteen years old. In the very same letter in which she expressed her grief at her sister’s death, she told the Superintendent that “I will try to return the latter part of September to Carlisle to continue my studies.” She wanted to “be placed with the graduating class as I certainly worked hard this winter with my studies at the Moorestown High School.” She wanted confirmation that she could return, so she asked the superintendent to “let me know if I can be entered in the ‘Fourth Year vocational’ class and I will return just as soon as I can before I get too far behind with my studies.” She hoped as well that the school would consider admitting her stepsister Elsie. Carlisle mattered to Delia.

She never returned to “dear old Carlisle.” She was told that she did not have “sufficient credits to enter the class which is to complete the course in another year.” She should return to Moorestown High School and then, at “the opening of the year you will be given the opportunity to take whatever work for which you are prepared.” Her last date of attendance was listed as May 31, 1916. It is not hard to believe that when Carlisle closed a short time later, she may have seen this as a loss for her people. As Onondaga chief Jesse Lyon asked, “Why was Carlisle closed? Nobody know,” he said. “Too good for Indian, maybe, but that is what Indian needs.”

THE STORY OF CARLISLE is not a simple one. As historians we know to be attuned to ambiguity and ambivalence. It is proper to view boarding schools as American institutions directed toward cultural genocide—the erasure of Native American culture, values, and beliefs. It attempted to play that role. But it did not always succeed. Students were homesick, at times. Some ran away from the school, especially the boys. Some returned to their communities feeling as if they no longer belonged. Yet there were Onondagas who ran away from home to get to Carlisle. Some of those runaways were not heading home, but to visit girlfriends. It is proper then, to view Carlisle as well as a flawed institution which Native American students attended to receive an education and learn crafts and trades, or to play sports or to play music, opportunities that were often closed to them elsewhere. More than one thing can be true at a time. Carlisle took and it gave, but it neither destroyed nor erased, the Onondagas who attended it between 1879 and 1918. The Interior Department’s Boarding School Initiative will need to be attuned to the school’s ambivalent legacy.