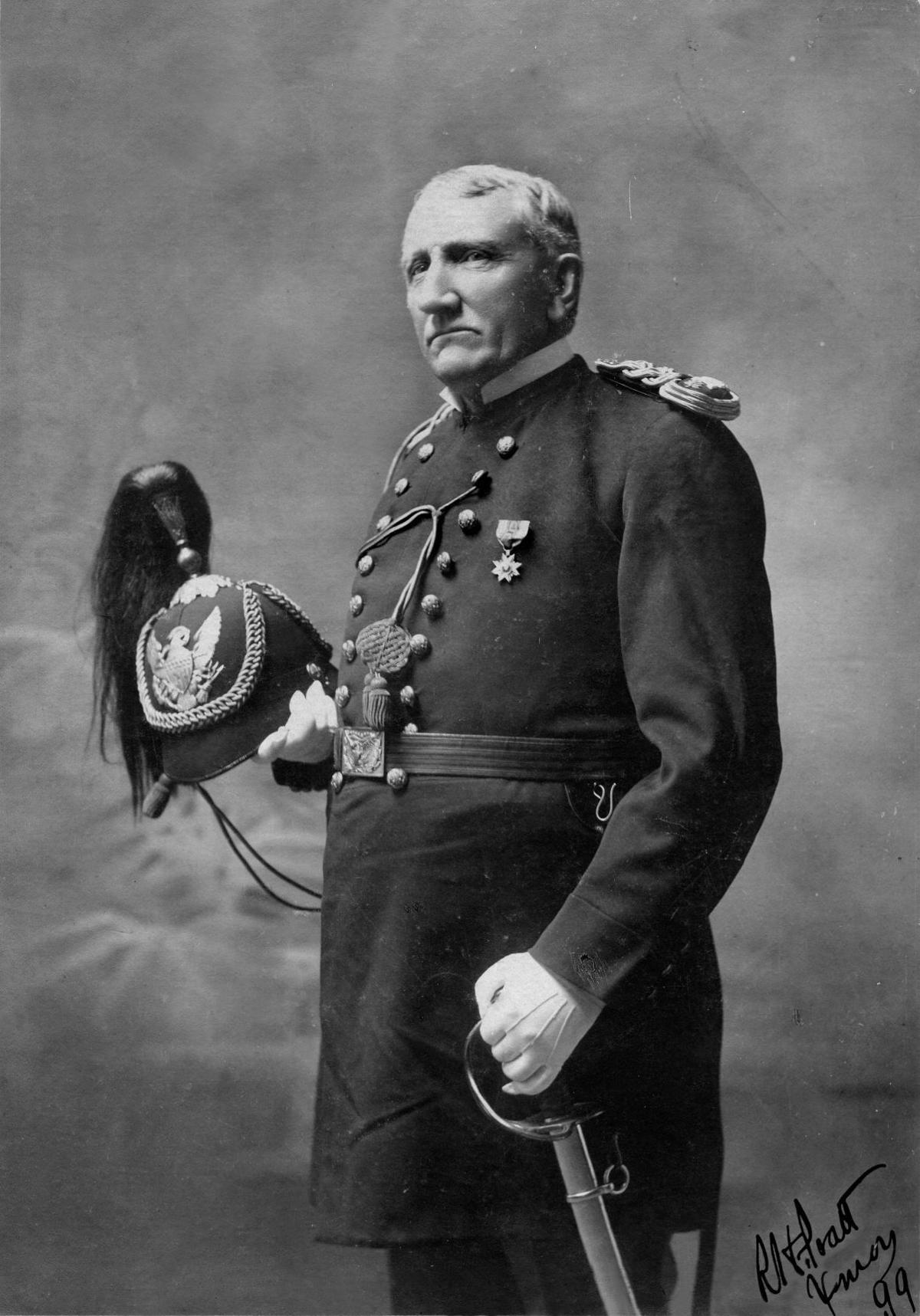

Because I teach a first year writing seminar at my college on the history of the Carlisle Boarding School, I have spent a fair amount of time reckoning with the words and deeds of Colonel Richard Henry Pratt, the Indian’s school’s founder and chief propagandist.

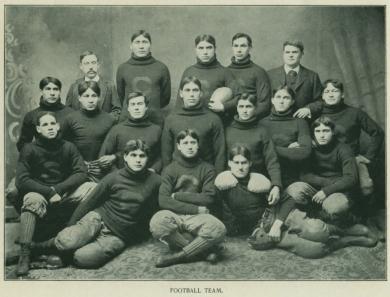

The school’s history fascinates me. In my own research on the history of the Onondaga Nation, I have followed those who attended the school through its records and reconstructed their lives as much as the evidence permits. Like my students, I make use of the digitized school records available at the Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center.

One thing I have not done is visit Yale’s Beinecke Library, where Pratt’s personal papers are housed. I have read his published writings, and in them I find it difficult to detect any self-doubt, any questioning, of the school’s fundamental premise: to best prepare Native American men and women for citizenship and participation in the American body politic and economic system, they must be removed from their homes and educated away from the reservation.

Pratt was quite explicit about this. The attachments of home generated a powerful pull. Even boarding schools located on reservations could not work, Pratt believed, because the sights, sounds, and scents of home provided a powerful distraction. Best to remove the students entirely. Speaking to a gathering of Baptist ministers, Pratt said that “In Indian Civilization, I am a Baptist, because I believe in immersing the Indians in our civilization and when we get them under holding them until they are thoroughly soaked.” Because of his tendency to make statements like these, scholars and the interested public describe the boarding schools as brutal institutions. Pratt, they say, acted with genocidal intent. He said, indeed, that he hoped to “kill the Indian,” and save the man.

There is no doubt that there was cruelty, brutality and short-sightedness. There was coldness and callousness and inattention. Some students resisted. One of my students is working on a paper I very much look forward to reading on firestarters, girls who set fires at Carlisle and were expelled. Yet the graveyard at the school contains the bodies of students who died far from home, the victims, in Calvin Luther Martin’s phrase, of “blundering goodwill.” Efforts are underway to repatriate some of these children, to return their bodies to their homelands. There are stories at Carlisle to melt a historian’s heart.

At the same time, we historians generally find simple morality tales uninteresting, because the past is always more complicated. For example, I recently reviewed a book by a historian named Keith Burich about the Thomas Indian School in New York, located on the Seneca Nation’s Cattaraugus Reservation. Thomas was open for a century, from the 1850s to the 1950s. There are people alive today who attended Thomas. The consequences of the school’s treatment of Iroquois children, Burich writes, were horrific. The school’s policies and its approach created in the students “a state of dependency and perpetual childhood that guaranteed the students’ inability to adjust to life outside the institution.” Arriving at Thomas from families broken by the forces of colonialism, “the same ‘pathologies’ that landed them at Thomas—poverty, divorce, alcohol abuse, and domestic violence—followed them when they left, ensuring that there would be future generations of Thomas students.”

Yet the evidence that Burich provides suggests that he may not be attuned enough to the school’s ambivalent legacy. The Mohawk Andrew Herne, disappointed by the public school opportunities at home, hitchhiked to Thomas to enroll. Burich points out that for many of the children, “Thomas provided a far better educational opportunity than the public schools on or near their respective reservations.” The Seneca Arthur Nephew remembered the school as the best part of his life. “We were taken care of, we had shelter, we had food, we had medical care, we had all kinds of recreation, and all kind of trades we could learn,” he wrote. Thus it appears that Burich’s claim that the school left children “unable to survive outside an institutional setting where every aspect of their lives was dictated and controlled by the institution” is an oversimplification at best, that underestimates the resilience and toughness of Iroquois families and children. His claim that the school left its students shattered in self-esteem and “unable to adjust to life after Thomas” seems inadequately supported and, indeed, contradicted by some of the evidence he presents. There was suffering to be sure, as Iroquois people have pointed out. But there was more to Thomas than that.

And Carlisle, too.

Pratt left Carlisle in 1904. Robert Utley, who wrote the introduction to the University of Oklahoma Press edition of Pratt’s From Battlefield to Classroom said that the school’s founder “retired.” Technically that is correct. But Pratt left under duress, and a number of powerful critics of the entire off-reservation boarding school enterprise had emerged in the early twentieth century, most notably Francis Leupp, who served as Teddy Roosevelt’s Commissioner of Indian Affairs.

Utley said that Pratt retired to Rochester, New York, where I live. Other sources say the same thing. The Rochester Public Library has done an incredible job of digitizing its local history resources, so I set off in search of the retired Colonel Pratt. His name does not appear in any of the published city directories, nor does that of his wife or any of his children. I asked friends for help, and I followed some other leads, but still no luck. Where was Colonel Pratt? I did not know, and I worried that Utley might have been wrong.

I am fairly certain that if I had limitless time and limitless resources, and no family and no need to do things other than history, I could have made the trip over to New Haven. I bet there are answers there about Pratt’s time in Rochester. But I don’t, and I couldn’t, so I didn’t, and the staff at Yale did not answer my email queries.

I poked around a bit more and I found what I was looking for in the newspapers. Pratt had daughters, and they married. It did not take long to figure out that his son-in-law Edward M. Hawkins lived in Rochester, on Highland Avenue, a five-minute bicycle ride from where I live (I know. I tried it).

I am not sure how much time Pratt spent in town, but he was in Rochester often. In retirement he spoke out against the Indian Bureau, and the “ethnologists” whose work informed the critiques of Pratt’s program for Carlisle. Long after off-reservation boarding schools had fallen out of favor, he continued to champion the entire effort as worthwhile and significant. He was proud of Carlisle, and he seems to have kept in touch with former students and even attended a reunion of former Carlisle students in 1913 in Akron, New York, near the Tonawanda Seneca Nation.

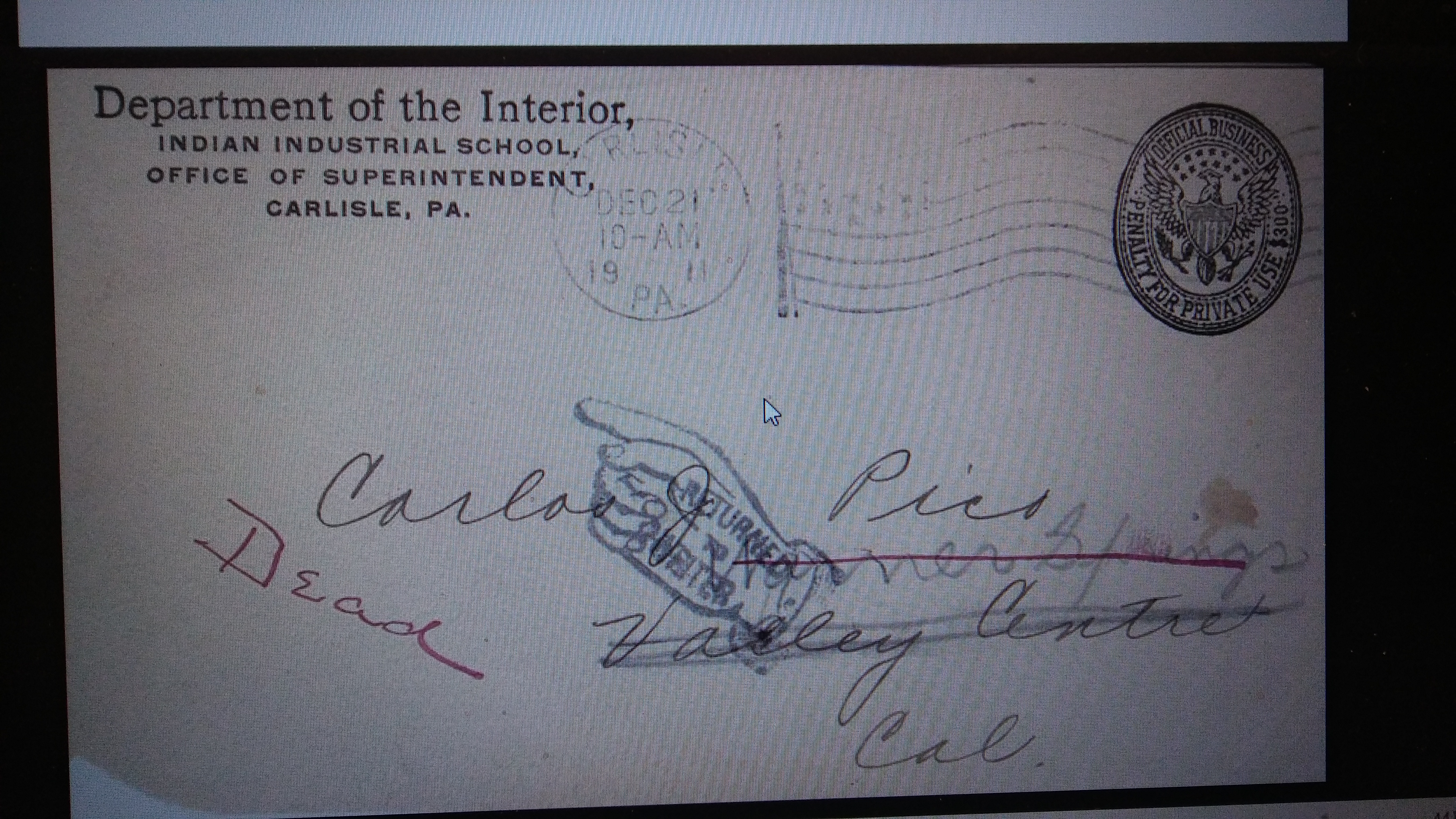

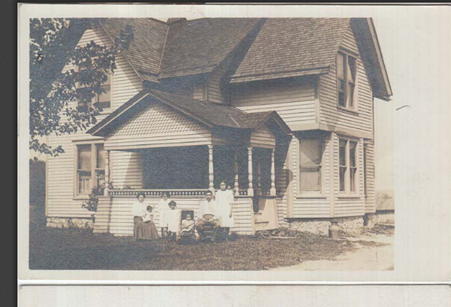

Just a couple of dozen Tonawandas attended Carlisle. More than three hundred went to Thomas. Of those who went to Carlisle their experiences seem to have mirrored those of other Haudenosaunee people who attended the boarding school. Some appreciated their time at the school and expressed their gratitude to Pratt and to his successors as superintendent. Daisie Doctor Snyder, for instance, in 1907 expressed her regret that she would not be able to return to Carlisle for that year’s commencement ceremony. She missed “Dear Old Carlisle,” and wrote that “I only hope this Commencement will surpass all others, and that the out going class are prepared to stand the hard knocks of the cold world and to fight a hard battle for the right and also to still uplift our race. Rosalie Doctor Poodry invited the administrators at Carlisle to visit her at her handsome, two-story frame house in Basom, New York, and said that she would love to send her children to Carlisle someday. She sent the superintendent a postcard,

with a photograph of the house. The baby, a little girl named Marion, had died a few weeks before she mailed the card, and Rosalie understandably still was broken up. As much as she looked forward to reading the school newspapers that she received in the mail, she asked that they not say anything about her dead child.

Rosalie Doctor Poodry’s letter was intimate and revealing. Other Tonawandas told the school what they were up to, but did not share too much more than that. Hiram Moses was farming forty-five acres of reservation land, and working when needed on the state highway. He attended the Presbyterian church on the reservation. Joseph Poodry lived in Buffalo. He worked at the Pierce Arrow plant there, and managed the Seneca Indian baseball team.

Others said little about their time at the school, chose not to keep in touch, and did not reply to the school’s questionnaires. Many of them returned to the reservation and lived lives that would have differed little from what they might have experienced had they never gone away to school Some succeeded, and attributed their successes to what they learned at Carlisle. Others did not do so well. Perhaps their hardships stemmed from the dislocation caused by the years they spent away, or the difficulties they faced in reintegrating themselves into the community after they returned.

Yet despite the boarding school experience, the criticism of their culture they routinely listened to there, and their years away from home, Tonawanda remained an indigenous homeland. Despite the efforts of the state to break up their lands and dispossess them, a story the Tonawandas knew all too well, they remained native peoples. And they asserted this, publicly and frequently, in ways that Pratt could not have missed.

Colonel Pratt is one of the villains in Native American history. He spoke of eliminating Native American cultures, and carried out his policies, for a time, with the enthusiastic support of American officials. But if he really believed the erasure of Indian identity was an attainable goal, he could not have missed the reality that he failed spectacularly. His legacy is ambiguous, and defies easy categorization.

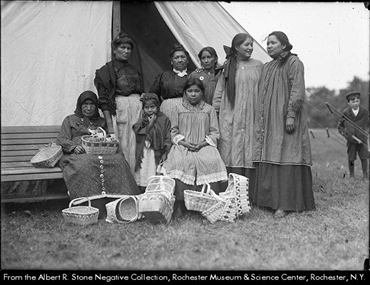

Every year, Tonawanda Senecas came into Rochester. I am pretty certain they were in town when Pratt was there, too. The Tonawandas went to Maplewood Park, one of the city’s popular gathering places. They set up a stage. They advertised their gathering in the papers, and the press attended and described what they saw. The Tonawandas routinely adopted and granted names to powerful white men, like Mayor Hiram Edgerton, in this photo housed in the collections of the Rochester Museum and Science Center. And as white Rochesterians gathered, and watched Indian

teams play baseball and demonstrate their lacrosse skills, and as they purchased the baskets and other items of craft produced by Tonawanda Seneca women, the Tonawandas danced.

The men wore ribbon shirts and their gustoweh. Women wore their calico dresses, their moccasins. They dressed in the traditional attire of Haudenosaunee people, with a few Plains-style feather headdresses thrown in for good measure. I like to think that Pratt, if he was in town, would have attended. He liked native peoples, after all, and liked to meet with former students. And in front of him, and white audiences who easily imagined that native peoples were part of the past, and who supported the allotment of their lands, the dissolution of aboriginal culture, and the erasure of their language, they gathered in the center of Rochester. They danced, and they proceeded to proclaim that they were still here, and that here they would remain. They were supposed to have been gone long before. If warfare or the dispossession of the nineteenth century didn’t get them, assuredly they would disappear as the century progressed. But here they were, in the middle of an important industrial city, announcing to all who cared to watch that anything the forces of colonialism might throw at them, they would survive as native peoples.