I am teaching for the first time a freshman writing seminar on the history of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. The students have read a couple of secondary works, but the bulk of their work will involve research in the documents collected by the Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center. It is an amazing resource, filled with revealing records from the school, but also amazing human stories.

The students are selecting the topics for their research papers. They obviously cannot go through the thousands and thousands of student records, and much of my time meeting with them last week was directed towards trying to help them narrow their topics down to a manageable scope and size. One way to do that was to follow the students from a given native nation, to explore their experiences at the school, and as much as possible, to try to figure out how they fared once they left.

Only a small number of the students are history majors, and they come to the work with a wide range of interests. Some of the delight in teaching the course comes with working with these diverse students, and approaching the records anew, from the perspectives of, say, education, or psychology, or epidemiology, or nutrition. I learn a lot from working with these students, and find myself constantly forced to think about the sorts of stories these records can tell.

I keep coming back to the human stories, of young people, often far from home, who came to the school, experienced it, and then moved on. Carlos Pico was one of those students.

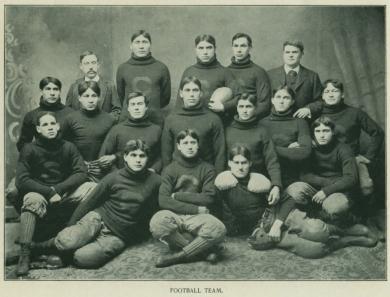

Carlos was 17 when he came to Carlisle in 1899. Last Thursday, the 7th of March, was the 120th anniversary of his arrival at Carlisle. Carlos was huge, six-and-a-half feet tall, 174 pounds. There is a story that he played on the Carlisle football team under Pop Warner, who coached at Carlisle from 1899 to 1903 and from 1907 to 1914. Carlos was at Carlisle for the first part of that period, but he left the school in June of 1904. I am not certain that he played. He is not listed in a newspaper article on the school football team in 1900. His student file shows that his outing–in Mt. Airy, New Jersey, and in Penn Valley and Morrisville, Pennsylvania, ran from the spring until late August or early September. If Carlos played on the 1900 team, he was not included in this picture of the players.

We do know that by 1905 Carlos was home in California and working as a farmer and a blacksmith, using the training he received while away from home. In May of 1910, he married Thomasa Penna. She was a Mission Indian, too, living in California. As he responded in August of that year to a Carlisle questionnaire, he had “a happy home my wife and my self.” He had “enough horses to do my work. And enough money to carry me on.” But something went wrong.

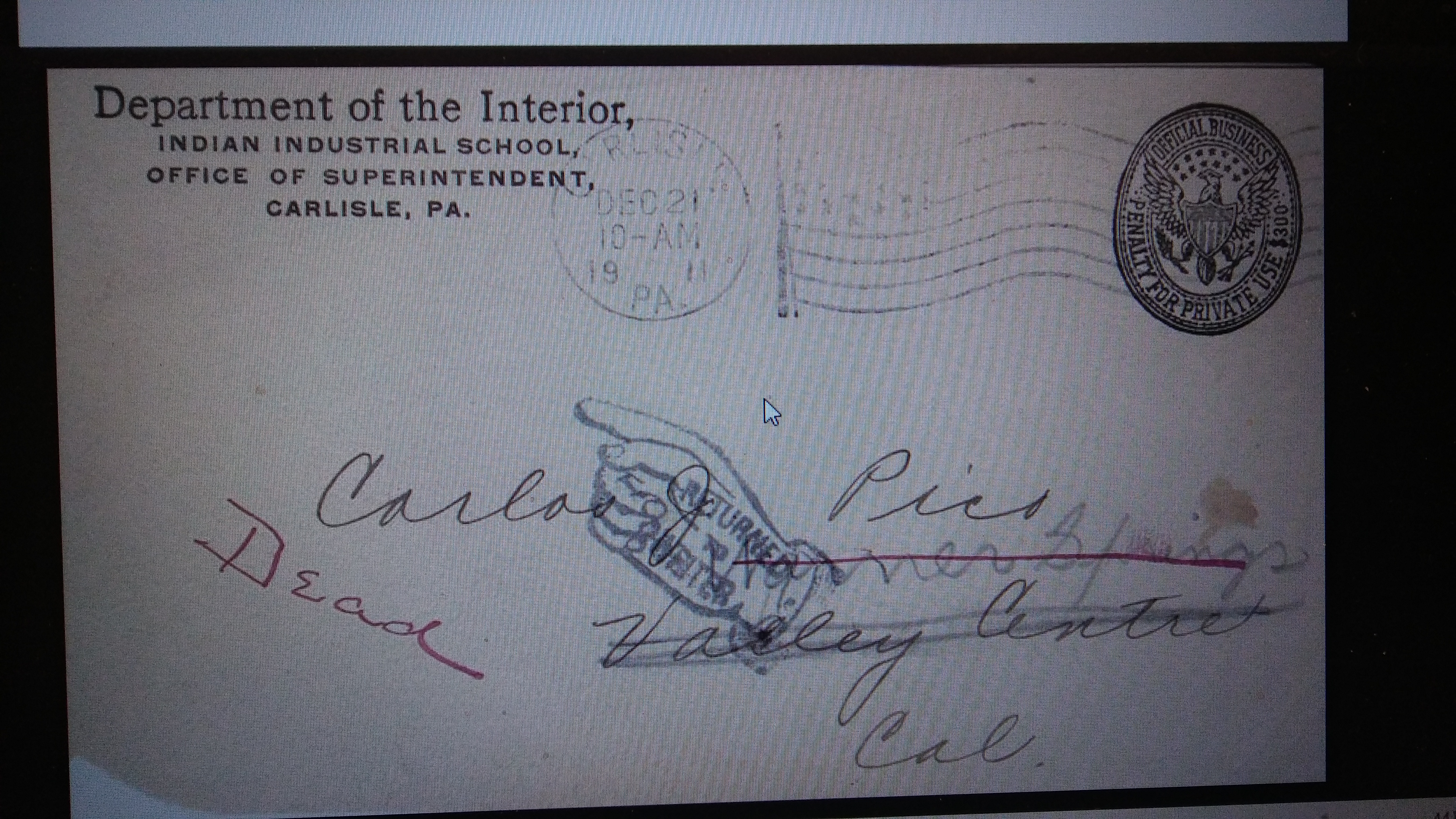

Carlos’s student file includes a pair of newspaper clippings. One read that “We regret very much the death of Carlos Pico of Rincon, who was brought to Pala Thursday in critical condition. The death of his wife, which occurred recently, preyed so heavily on his mind that he became mentally unbalanced and died Saturday morning.” Another read that “An Indian, Carlos Pico, of Rincon, California, grieved so over the death of this wife that he lost his mind. Death soon come to his relief.”

It’s hard to know what to do with stories like this. Grief saturates the story of Carlos and his wife. It is difficult to imagine the loneliness and a depth of grief so consuming that it produced in this young man derangement and self-destruction. I have poked around a bit. Carlos is still remembered and still has relatives in his community. Much of his story nonetheless remains out of reach. Perhaps county records might reveal more. Perhaps there is more that can be learned about is wife (Thomasa Penna? Tomasa Pena? It is hard to be certain of the actual spelling of her name). A historian would have to spend some time on the ground in California, hitting the archives, looking for needles in different haystacks. Stories like this leave students grasping for more, and they teach the difficulties that come with historical research. Sometimes we can only go so far. Trails grow cold, the lineaments of the story difficult to trace. But they connect students to the past at an emotional level, and call them to dig deeper, and to recognize that the work of reconstructing the past is never complete. As a historian, and as a human being, it is hard to forget stories like these.