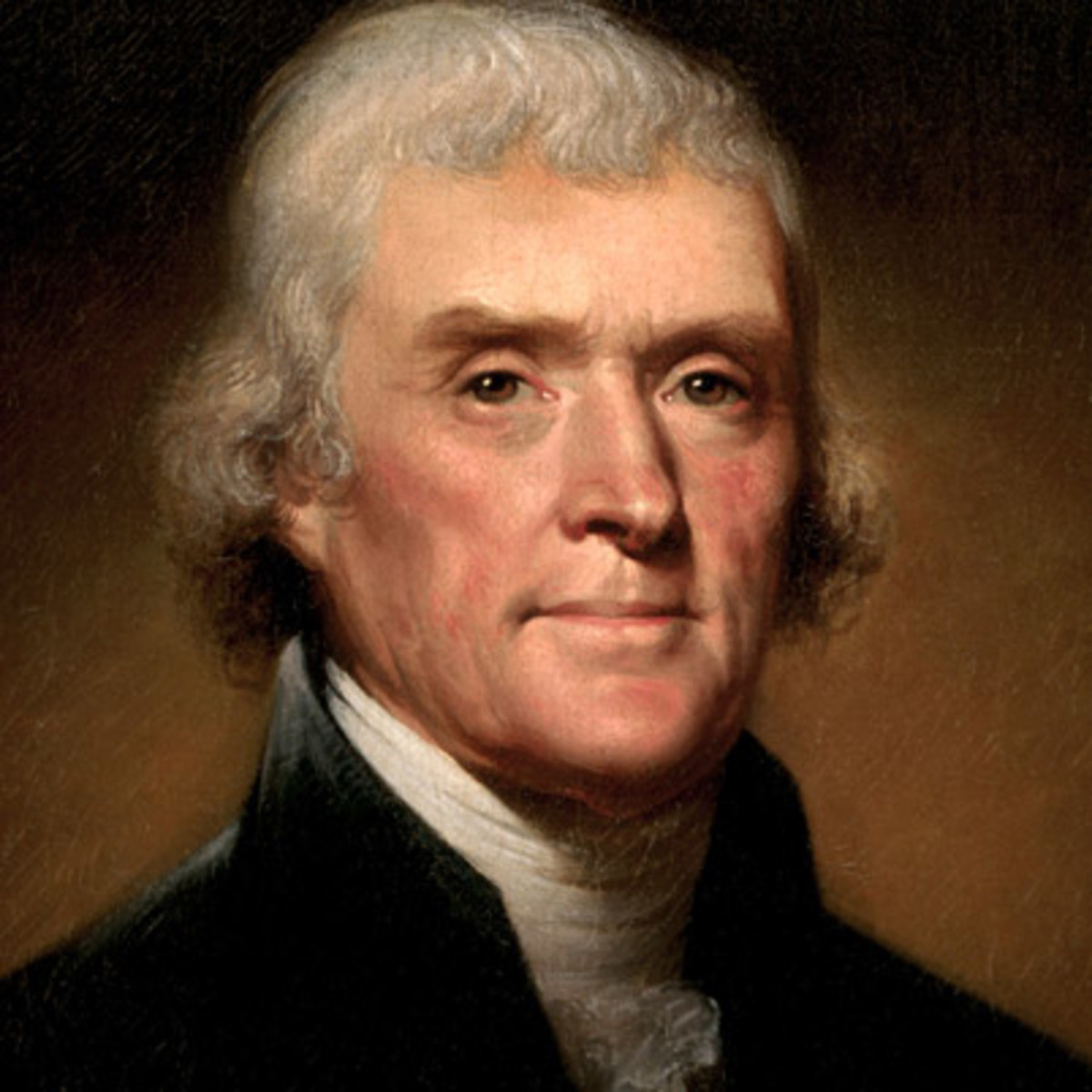

One letter more than many others encapsulates Thomas Jefferson’s Indian policy. On this day in 1803, Jefferson wrote that letter to William Henry Harrison, then the governor of Indiana Territory.

My first paper in grad school was an exploration of Jefferson’s Indian policy. Wish I still had a copy of that. Jefferson’s views of Indians, I believed, were shaped by his understanding of the Ancient Saxons who inhabited England in the centuries before the Norman Conquest. Among Jefferson’s favorite books were Arthur Gordon’s translation of Tacitus, which included a long, running commentary in the notes comparing the Ancient Saxons to native peoples in America; or the works of the Scottish historian William Robertson or the Scottish philosopher Adam Ferguson, both of whom saw connections between the ancient inhabitants of the British Isles and Native  Americans. It is, as I pointed out in my first book, a common theme in English thought about native peoples. When Theodor DeBry etched his engravings based on the artwork of John White, who painted those memorable images of the Carolina Outer Banks in 1585, he included pictures of the “Picts” in order to show that “the inhabitants of the great Bretannie have bin in times past as sauvage as those of Virginia.” At Jamestown, William Strachey, John Rolfe, and many others pointed out that the ancient inhabitants of the British Isles had once lived like the Algonquian peoples they then were encountering.

Americans. It is, as I pointed out in my first book, a common theme in English thought about native peoples. When Theodor DeBry etched his engravings based on the artwork of John White, who painted those memorable images of the Carolina Outer Banks in 1585, he included pictures of the “Picts” in order to show that “the inhabitants of the great Bretannie have bin in times past as sauvage as those of Virginia.” At Jamestown, William Strachey, John Rolfe, and many others pointed out that the ancient inhabitants of the British Isles had once lived like the Algonquian peoples they then were encountering.

Historians like Ronald Meek, Hugh A. MacDougall, H. Trevor Colbourn, and Arthur Ferguson all explored this style of thinking. All societies passed through four stages as they became m ore civilized, beginning with hunting and gathering, graduating from there to a pastoral mode of living, to settled agriculture, and, finally, the urban life of the city. In his famous book on Jefferson’s economic thought, Drew McCoy argued that Jefferson struggled throughout his career to preserve for America the third stage, to keep the country an agrarian republic and, he hoped, to avoid the inequality and brutality he perceived in urban life.

ore civilized, beginning with hunting and gathering, graduating from there to a pastoral mode of living, to settled agriculture, and, finally, the urban life of the city. In his famous book on Jefferson’s economic thought, Drew McCoy argued that Jefferson struggled throughout his career to preserve for America the third stage, to keep the country an agrarian republic and, he hoped, to avoid the inequality and brutality he perceived in urban life.

I left this project behind long ago. It strikes me now as too much a project about books, too much discussion of what was going on in Jefferson’s library and in the intellectual centers in Europe and America instead of what was going on in native towns and villages, where my interests lie now.

Still, there is little doubt that Jefferson believed that native peoples, like the Ancient Britons, could progress from their “primitive” origins. Two years before his death, Jefferson spelled this out on a broad, continental scale in a letter to William Ludlow. “Let a philosophic observer commence a journey from the savages of the Rocky Mountains, eastwardly towards our sea-coast,” he wrote. “These he would observe in the earliest stage of association living under no law but that of nature, subscribing and covering themselves with the flesh and skins of wild beasts. He would next find those on our frontiers in the pastoral state, raising domestic animals to supply the defects of hunting. Then succeed our own semi-barbarous citizens, the pioneers of the advance of civilization, and so in his progress he would meet the gradual shades of improving man until he would reach his, as yet, most improved state in our seaport towns. This, in fact, is equivalent to a survey, in time, of the progress of man from the infancy of creation to the present day.”

Jeffersonian “philanthropy,” the name that Bernard Sheehan gave to his Indian policies, was informed by this historical style of thought. As he told a delegation of Cherokee chiefs who visited him in Washington early in 1806, “You are becoming farmers, learning the use of the plough and the hoe, enclosing your grounds and employing that labor in their cultivation which you formerly employed in hunting and in war; and I see handsome specimens of cotton cloth raised, spun and wove by yourselves.” The President told the Cherokees that he was optimistic for their future. “You are also raising cattle and hogs for your food, and horses to assist your labors. Go on, my children,” he continued, “in the same way and be assured the further you advance in it the happier and more respectable you will be.” Become like us. You will live better. And as you do so, you will need less land, which we shall be happy to take off your hands. Taking, as Gregory Evans Dowd put it, was portrayed as giving.

Respectability. In Jefferson’s view the Cherokees were making progress. Other Indian nations looked to the advancing Cherokees and found themselves wanting in comparison. That is what Jefferson believed. And, for the Cherokees, this was only the beginning.

You will find your next want to be mills to grind your corn, which by relieving your women from the loss of time in beating it into meal, will enable them to spin and weave more. When a man has enclosed and improved his farm, builds a good house on it and raised plentiful stocks of animals, he will wish when he dies that these things shall go to his wife and children, whom he loves more than he does his other relations, and for whom he will work with pleasure during his life. You will, therefore, find it necessary to establish laws for this. When a man has property, earned by his own labor, he will not like to see another come and take it from him because he happens to be stronger, or else to defend it by spilling blood. You will find it necessary then to appoint good men, as judges, to decide contests between man and man, according to reason and to the rules you shall establish. If you wish to be aided by our counsel and experience in these things we shall always be ready to assist you with our advice.

Not all of them wanted that advice, and when they did, it was on their own terms. Jefferson’s philanthropy always walked hand in hand with coercion, and that is what makes his letter to William Henry Harrison so revealing. His philanthropy, as Bernard Sheehan put it so long ago, contained within it the “seeds of extinction.” Jefferson’s solution to the “Indian Problem” was to make Indians disappear. Either they would assimilate and blend into the American body politic, or they would leave. Jefferson pursued the removal of the Cherokees long before Andrew Jackson became President. And native peoples, quite clearly, never saw much attractive in accommodating themselves to his understanding of the path they should take. And when native peoples ignored or resisted his efforts, which in essence involved compressing his understanding of a millennia of English history into the prescription for the eight short years of this presidency, he used all means necessary to remove them.

So, back to Jefferson’s letter to Harrison.

You will receive herewith an answer to your letter as President of the Convention: and from the Secretary at War you receive from time to time information & instructions as to our Indian affairs. these communications being for the public records are restrained always to particular objects & occasions. but this letter being unofficial, & private, I may with safety give you a more extensive view of our policy respecting the Indians, that you may the better comprehend the parts dealt out to you in detail through the official channel, and observing the system of which they make a part, conduct yourself in unison with it in cases where you are obliged to act without instruction.

When historians see something like this, their eyes light up. Jefferson is writing with no other audience in mind but Harrison, and here he will be frank, open, and honest, words not usually used to describe him.

Our system is to live in perpetual peace with the Indians, to cultivate an affectionate attachment from them, by every thing just & liberal which we can do for them within the bounds of reason, and by giving them effectual protection against wrongs from our own people.

Jefferson was well aware of the Trade and Intercourse Act, which attempted to regulate those instances where native peoples and white Americans came into contact. The laws were geared towards keeping the peace, avoiding a dust-up that might lead to a wider war. But as white people arrived in the vicinity of Indian settlements, even those who were peacefully inclined, changes occurred on the land. “The decrease of game rendering their subsistence by hunting insufficient, we wish to draw them to agriculture, to spinning & weaving,” Jefferson told Harrison. Here is the civilization program described once again. And native peoples were willing to make some changes.

The latter branches [i.e. spinning and weaving] they take up with great readiness, because they fall to the women, who gain by quitting the labours of the field for those which are exercised within doors. When they withdraw themselves to the culture of a small piece of land, they will perceive how useless to them are their extensive forests, and will be willing to pare them off from time to time in exchange for necessaries for their farms & families.”

Jefferson wanted the process to move quickly. “To promote this disposition to exchange lands which they have to spare & we want, for necessaries, which we have to spare & they want, we shall push our trading houses, and be glad to see the good & influential individuals among them run in debt, because we observe that when these debts get beyond what the individuals can pay, they become willing to lop th[em off] by a cession of lands.” Debt as a tool leading to dispossession: it is all here in Jefferson’s letter. And he continued:

At our trading houses too we mean to sell so low as merely to repay us cost and charges so as neither to lessen or enlarge our capital. This is what private traders cannot do, for they must gain; they will consequently retire from the competition, & we shall thus get clear of this pest without giving offence or umbrage to the Indians. In this way our settlements will gradually circumscribe & approach the Indians, & they will in time either incorporate with us as citizens of the US. or remove beyond the Mississippi. the former is certainly the termination of their history most happy for themselves. but in the whole course of this, it is essential to cultivate their love.

And what else?

As to their fear, we presume that our strength & their weakness is now so visible that they must see we have only to shut our hand to crush them, & that all our liberalities to them proceed from motives of pure humanity only. Should any tribe be fool-hardy enough to take up the hatchet at any time, the seizing the whole country of that tribe & driving them across the Mississippi, as the only condition of peace, would be an example to others, and a furtherance of our final consolidation.

Jefferson reminded Harrison in the closing paragraph to keep this letter private, and by no means to allow the Indians to understand his devious scheme to draw their leaders into debts that could only be satisfied by the cession of their followers’ lands.

I find little to like in Thomas Jefferson. I have always felt that way. He was a beautiful writer at times, but he frittered away his talents. I think here of his discussion of race in his Notes on the State of Virginia or his sad and creepy letter to Maria Cosway. He was seldom courageous, more adrift in than in command of the intellectual currents that swirled about him. And he was almost never direct. His letter to Harrison, in this sense, is indicative of his policies and his character.