Like many professors, I have learned a lot this past Pandemic Spring teaching at my small, under-funded, public liberal arts college in Western New York State. Most of all, I have learned much about the strength and resilience of my battered students. I have been amazed by their ability to complete their work in the face of significant disruptions in their lives and, in a few cases, horrifying stories of personal tragedy and grief. I have had students email me their papers from their cars, sitting outside a McDonald’s with its free wi-fi.

I have also learned that so many “thought leaders” and “change agents” writing about the future of higher education seem to have very little sense of what it is that we college professors do in the classroom. Many of them seem to write from the Ivy League. They appear to have no familiarity with the sorts of colleges and universities most American college students attend.

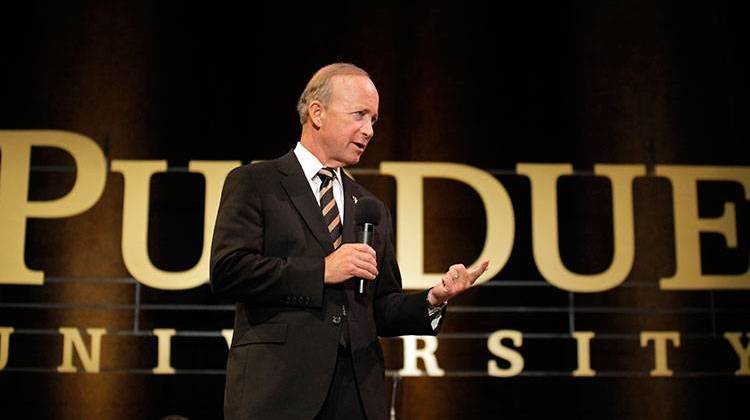

Whether we are talking about Purdue President Mitch Daniels’ suggestion that professors wall themselves off from their classes with a prophylactic plexiglass shield, or others’ suggestions that our Zoom lectures can be packaged, marketed, and reused to create economies of scale in academia, the fact of the matter is that few of us lecture any longer. The “sage on the stage” model is old and less effective than other methods in reaching today’s students. This is not a lament about “kids these days.” It is, rather, exciting, a development that brings a vibrancy to the classroom that makes the learning experience more rewarding and impactful for all.

We are neither talking heads nor orators bound to a lectern. Our classes are not one-way streets, with faculty speaking and students listening. We move around the room. Our students do, too. In my history and humanities courses, I try to talk with, rather than at, students. True, some instructors lecture very effectively and engagingly with their students, but too often this mode of instruction renders students passive. They absorb “course content” which is often supplemented by massive, expensive textbooks (True Story: No college professor reads a textbook for enjoyment or out of interest, yet too many of us expect our students to do so). Students in these courses take notes, periodically regurgitate what they think is important, but otherwise play little active role in their own education. It is rote and it is terribly dull, but a lot of people think it is what we do.

It is not. College classrooms look much different today than they did when I was an undergraduate student in the 1980s.

We know it is better to have students learn by doing. Students in the liberal arts and humanities learn by asking questions, and by listening, conversing, and engaging in discussion and debate. They collect evidence, read critically, and analyze. We work hard to create critical thinkers and writers. In my classes, we discuss the sources to assess their strengths and weaknesses, their biases and prejudices, and to see what sorts of information this source might yield. We urge students to consider their own preconceptions that might color how they interpret the past. And together we engage in urgent Socratic dialogue which exposes the weaknesses in our reasoning and forces us to confront long-held assumptions. Or job is to help students learn, and that is something so much more than merely distributing to them over video selected course content.

The content of our courses, after all, can change dramatically over time. History is not a static collection of names, dates, and places. Rather, it is the study of continuity and change, measured across time and space, in peoples, institutions and cultures. History is not a science, but it is a discipline, as we set out to answer the questions that present themselves to us in a deliberate, systematic, and rigorous manner. The questions we seek to answer can change with the world around us. Not only does new scholarship force us to rethink old assumptions, but the world itself insistently raises questions about the way things are and the way things ought to be.

There are of course many different ways to teach effectively. Different academic disciplines lend themselves better to some teaching methodologies than to others. But we must dispense with the outdated notion that college professors provide rote course content by lecturing in ways that can be packaged and replicated semester after semester. So much student learning takes place in libraries and in the archives, in faculty offices and in the hallways outside the room before and after class. Students learn through internships and through working closely with faculty mentors on research projects.

There has been so much loss over the course of the past three months. The inconvenience and financial blows colleges and universities are experiencing may pale in comparison to the needless suffering of so many families across the country. If, however, higher education is deemed in need of reform, I would urge these advocates to reflect upon the best learning experiences they had themselves in college. It likely was not something that took place as they sat in a massive lecture hall, or watched a video, or labored through a chunky textbook. To help higher education, let’s look towards adequately funding public colleges and universities, reversing the long-standing trend towards a highly continent teaching faculty. It is a smart, long-term, investment. Let’s equip faculty to provide students with the resources to provide students with the high-impact learning experiences that can awaken in them a new sense of the possible and that can change their lives.