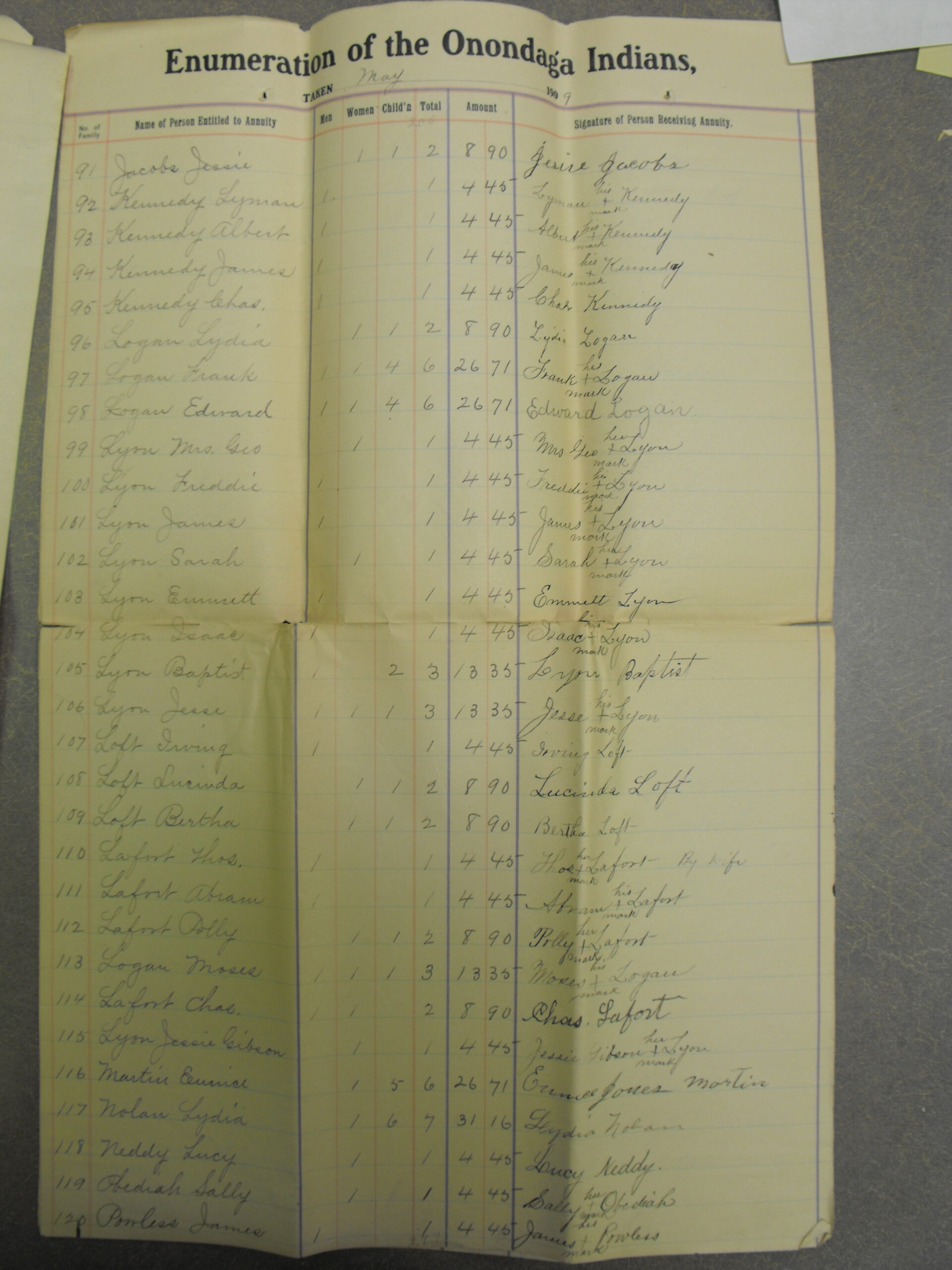

How did the “Spanish Flu” epidemic that hit the United States in 1918 affect the Onondaga Nation? I cannot tell for sure, but going through the census records kept by the Interior Department and the State of New York has given me some ideas.

We know that the epidemic did great damage in Native American communities. One scholar estimated that more than 6200 Native peoples died from influenza in 1918, 2% of the total Native American population. The Seneca Jesse Cornplanter returned home from his service overseas during the first World War to learn that his parents, sister, brother-in-law, and two children had died. Joaqlin Estus’s piece in Indian Country Today from last February highlights some of the massive desolation, with a particular focus on Alaska Native communities. Estus mentions Harold Napoleon’s Yuuyaraq, one of the most powerful and important indigenous assessments of what the epidemic meant. I have assigned it to my students, and I encourage you to consider it as well.

In 1918 418 Onondagas lived on the Nation Territory located a bit to the south of Syracuse, New York. Another 128 Oneidas lived on the reservation. Between July 1, 1918 and June 30, 1919, nine Onondagas and seven Oneidas died. Some, like Mary Jones, were elderly, and some were very young, like Eliza Homer’s baby boy. Two had attended Carlisle. Jerry Homer I have written about on this blog in the past when I knew less about him. Eva Waterman was a popular rebel at the Boarding School, expelled for her behavior. She was a talented student, but O. H. Lipps, the school’s superintendent, wrote to Eva’s mother in 1913 to tell her that “because of continued misconduct your daughter Eva Waterman, will be returned to you tomorrow. Her influence for the bad,” Lipps continued, “is so great that I deem it advisable to separate her from the rest of our girls.” He said he was sorry that he had to do this. She was, according to one report of her outing, “impudent at times.” She had a smart mouth, and she made the other students laugh. She had influence. In a letter from “Behind the Bars” to “Dearest,” undated, Eva wrote from one of her outings to a friend back at Carlisle. She missed her friend, and she missed the school. She said that it was good to receive a loving letter from her because “the only kind I hear is these coarse, hoggish, indigestible commands.” A Carlisle investigator, looking into Eva’s complaints about one of her outing situations, found that she spent her time lying around in the hammock, playing croquet, and reading. She was impudent. She had little interest in farm work and she ran away. To me, she sounds like a teenager, a kid, who refused to take the adults around her seriously. But she needed to be broken. One of the matrons at Carlisle suggested that for Eva “all privileges might be taken away and work all day in the laundry might be required for a certain length of time and if possible she should be prevented from communicating with the girls and making herself a heroine instead of a failure.” It did not work and she was sent home. She spent some time living in Syracuse, and at other times she lived on the Nation Territory. She was still a young woman when she died.

The census records do not tell us the causes of death for these individuals. It is worthy of note that during this twelve-month period which contained the peaks of the influenza epidemic fewer people died than during the previous year. From July of 1917 until June 30 1918, twelve Onondagas and 9 Oneidas died. From July of 1916 to the end of June in 1917 thirteen Onondagas and three Oneidas died.

The evidence suggests that a fourth wave of the Spanish Flu hit New York City and other locations around the country early in 1920. And between July 1 1919 and June 30 1920, nineteen Onondagas and four Oneidas died. Some of the relatively large number of Onondagas who died had lived long lives. Joshua Pierce was in his mid-90s. Mary BigBear and Abner Printup both had been born in 1836. Others were struck down in middle age. Nine of the Onondagas who died were under thirty years old. Lavina Hill and Lena Jacobs both were around five years old. David George and the “Baby Isaacs” were just one. Bernice Jacobs, George Archie Logan, and Florence Tallchief all were teenagers.

Other diseases, or accidents, could have killed people. Life could be fragile in the early twentieth century. Death could strike suddenly. Tuberculosis was a steady enemy of Indigenous peoples’ health. There is much we cannot know, but the leap in the number of Onondaga deaths between 1918-19 and 1919-20 is striking. Nearly twenty people dying in a community of a bit more than 400 would have been felt acutely, especially with the deaths of so many young people who should have had so many more years to live. These deaths, however, did not draw the attention of local journalist or the legions of judgmental observers who criticized the Onondagas for their backwardness and continued embrace of “paganism.” And they would have gone unnoticed by me had I not devoted the past month to reading through these figures. This is the sort of work we must do, even if it is only a start. Each death, in a community where there were no strangers, would have been a blow, with waves of grief that must have swept throughout the small community from the very young to the very old.

What’s it like to live in a community in which every single person in it feels the same grief at the same time? I have thought about this question a lot as I looked through these records. I have thought about it as well when I read the Jesuits’ 17th century descriptions of the epidemics that swept through Iroquoia, cutting jagged holes in the fabric of everyday life. Whether Spanish Flu, consumption, suicide or accident, or in our own time killer cops, the coronavirus, or colon cancer, these historical moments may lead some of us towards greater empathy. It is a difficult journey, and one we need to make.