Jesse Goldberg is a graduate of the institution where I teach, SUNY-Geneseo. Though I never taught him, I have followed his career on Twitter largely because he was spoken of so highly by a number of my colleagues. I have followed closely as well the recent controversy surrounding some of Dr. Goldberg’s tweets and the craven response of Auburn University, where he recently signed a one-year contract to teach.

Dr. Goldberg wrote on Twitter, “F*ck every single cop. Every single one.” He wrote that “the only ethical choice for any cop at this point is to refuse to do their job and quit. The police do not protect people. They protect capital. They are instruments of violence on behalf of capital.”

Strong words, indeed, but let’s not be too precious about this. You have heard this rhetoric during the back-and-forths on cable news, and you have seen “FTP” and “ACAB” and more written on walls on TV and quite likely in your hometown. Nonetheless, the right-wing reaction was predictable. The College Fix and similar sites went nuts. Alabama Congressman Mo Brooks called for Dr. Goldberg’s firing. Auburn’s administration clutched their collective pearls, shrieked “Oh My God!” and promised to weigh their available options in the face of such objectionable speech.

I have been in Dr. Goldberg’s shoes, though when I had this experience the internet was in its infancy, social media did not exist, and Montana, where I taught, was something of a closed circuit which by its nature contained the reach of the controversy. People on cell phones across the world could not read about what I had said and contact me immediately. Dr. Goldberg was not so lucky. He had it a million times worse.

I began teaching in Montana in the fall of 1994, right out of graduate school. That December, the National Center for History in the Schools published the National History Standards. I learned about them after stumbling across Lynne Cheney’s famous editorial in the Wall Street Journal. I saw the debate on CNN’s “Firing Line,” and thought I would read them for myself. Most of my students aspired to be teachers, and it struck me as the responsible thing to do.

I found nothing to object to in the Standards, and I said so in an editorial that appeared in the Billings Gazette. I argued the criticisms of the Standards came from those who objected to students learning about the history of BIPOC, Women, and non-elite Americans. I asserted that those who objected to the Standards did not argue in good faith.

I liked writing for the newspaper. More people would read one of my opinion pieces than any book I might write, it seemed, so a couple of weeks after the Oklahoma City Bombing, I wrote another one. There was at the time a lot of attention paid to Right-Wing militia groups like those to which Timothy McVeigh belonged. I wrote that these groups certainly were a threat, but I asked readers to consider that “the threat these marginalized groups pose may…pale in comparison when weighed against the recent explosions of discriminatory legislation and racially charged public discourse” taking place in Congress and in state halls across the country.

Both of these pieces pissed off a lot of people. I got mail at my home address, calling names and making threats. Menacing phone calls. It was unnerving.

I taught at the time in a deeply dysfunctional department. There was the angry historian of Revolutionary France, a Harvard Ph.D, who seethed with resentment. He had been denied tenure at the University of Rochester and, I believe, Case Western, and felt he deserved better than an open-admissions college in eastern Montana. Perhaps if he had written more and spent less time hanging around in the dorm lobbies, his career might have been different. Then there was the Missouri-Synod Lutheran Pastor, who said that being a history professor was the “best part time job in the world.” He reminded me of that “Joe Isuzu” guy from the old TV commercials. The department chair was an Iraqi Seventh-Day Adventist who believed, firmly, that African Americans and Native Americans came to Billings only because it was easier to commit crimes in the city than it was wherever they came from. And there was a self-proclaimed expert on lynching, who told me that he thought the Willy Horton advertisement was a perfectly reasonable attack on Michael Dukakis. When I asked him why Lee Atwater, the ad’s creator, apologized for it on his deathbed, I received no answer. Probably should not have asked that question.

Two of these guys—the historians of Revolutionary France and the expert on lynching—took my articles personally. They said that in my editorials I had, in effect, called them racists. I hadn’t, but perceptions, you know? At MSU-B, even though I was fortunate to be on the tenure track, my contract was renewed each year. And every year, the Missouri-Synod pastor and the department chair voted to keep me. Every year, the student representative on the committee voted to keep me. And the other two voted to fire me. Each of the four years I was there.

I am close to my dissertation director. We still talk regularly. I asked him for advice. He wrote me a letter and said that I should remember that for the Old School, new professors should be like the children of long ago: seen and not heard. I asked my dad for advice. He said “don’t get in a pissing contest with these guys.” He may have used some word other than “guys,” but I cannot remember. I was never happy in Billings, and the only thing that solved the problem was to leave. After I signed my book contract, I was hired in New York, and I never looked back.

I hear commentary all the time from people on the right denouncing what they call “cancel culture.” Their laments were embodied in the resolution recently announced by 2024 GOP Presidential Candidate Tom Cotton and two of his colleagues that calls for Congress to protect the “First Amendment rights of students at public universities from unconstitutional speech codes and so-called free speech zones.”

I am willing to concede that there are in my field closed-minded and dogmatic people. That is true for any field. Those who challenge certain orthodoxies might expect to be engaged in angry and urgent debate. Perhaps they will be “unfriended” on Facebook or no longer followed on Twitter. Perhaps one of their critics will show their anger as “Reader No. 2” when they submit their work for publication. THERE IS NOTHING NEW ABOUT THIS. CHALLENGING ORTHODOXIES ALWAYS PRODUCES A REACTION. It comes with the territory and, as my dad used to say in another line I grew up with, “if you can’t stand the heat, get out of the kitchen.”

What Dr. Goldberg faced is significantly different. Dr. Goldberg received death threats, and threats of violence. Social media makes it easier for those so inclined to spread terror, and no country makes it so easy for those who hate to do evil.

I have had profound disagreements with colleagues in my field. If you are a professor, it is likely that you have, too. No one in academia has ever threatened to kill me or hurt my children. Nobody at an academic conference has listened to what I said, or read what I wrote, and tried to get me fired. Write an opinion piece on the history of the 2nd Amendment, or pointing out that New York State is built on stolen indigenous land, however, and all hell breaks loose. Repeat the language coursing through American streets in the wake of the killing of George Floyd, and your life and career are in danger. Alabama’s Mo Brooks called for the firing of Dr. Goldberg. This from a representative who has lost no opportunity to debase himself for a President who boasts of his “pussy grabbing,” tells American-born congressional representatives to go back to where they came from, and dismisses those parts of the world where he does not own golf resorts as “Shithole countries.” You want to talk about objectionable and destructive speech? Please. Spare me.

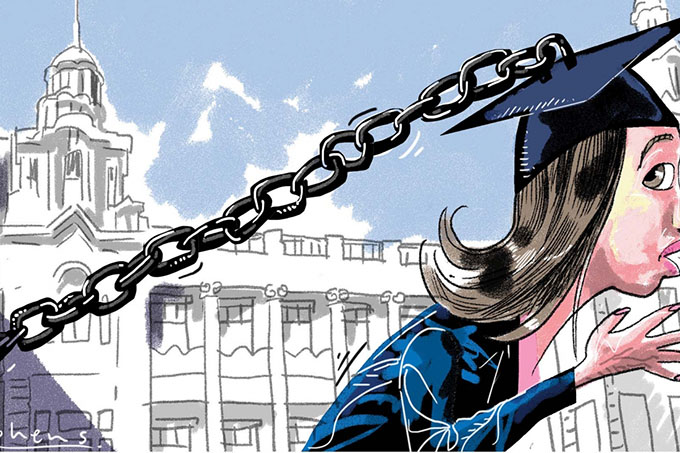

Academia is in dire straits right now. College budgets are broken. Some schools, I am told, might go under. Others are laying off faculty and staff. Graduate programs, meanwhile, are filled with immensely talented young scholars. Many of those who hope to pursue careers in academia will never get that chance. Tenure-track jobs are few and far between. The academic job market has long been horrible, but now it is even worse.

Maybe you dislike what Dr. Goldberg wrote on his Twitter account. Maybe you found it intemperate, impetuous, rash, and unwise. Maybe you find it disturbing, provocative, or objectionable. You are entitled to all those feelings. I do not know what baggage you carry with you that causes you to find Dr. Goldberg so threatening that you need to threaten his already tenuous career. But here’s the thing. You have no right not to be offended by things people say. As long as those words do not threaten violence, than hearing them is part of the price you pay for living in a free society. If you disagree, fine, enter into a debate. Argue. Pose your alternative. And steel yourself to face some criticism. But that sort of exchange requires a degree of intellectual courage that is getting harder and harder to find every day, especially on the Right.

Dr. Goldberg survived this. Auburn, seeking perhaps the path of least resistance, said that he would not teach, but that he would hold a research position this year. In support of Tom Cotton’s resolution, Georgia Senator Kelly Loeffler said that the proposed legislation will “ensure students on college campuses will be able to express their beliefs without the fear on censorship or retribution.” For students, this resolution is a solution in need of a problem. The senators are worried about leftists silencing students. They are chasing phantoms, while ignoring the very real assaults on freedom-of-thought launched by the political right. Whether we like or dislike what Dr. Goldberg wrote, we all should be in agreement that he has the right to say it.