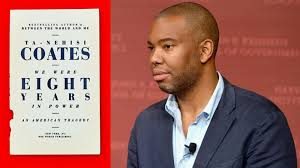

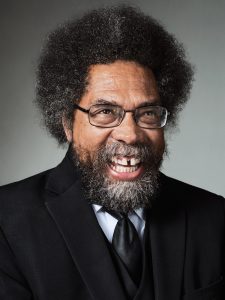

Students of Native American History could benefit from paying attention to the debate that took place earlier this week between Cornel West and Ta-Nehesi Coates. Coates wrote We Were Eight Years in Power and West reviewed that book in The Guardian. Since then, Coates has deleted his Twitter account after a lengthy exchange.

I like Coates’ work, a lot, though I have yet to read his most recent book. His article on white supremacy and the rise of Donald Trump was outstanding, and his essay making the case for reparations for slavery has sparked debates ever since it appeared in The Atlantic several years ago. West, however, was unimpressed, and he criticized how Coates “fetishizes white supremacy,” has a “preoccupation with white acceptance,” and an uncritical “allegiance to Obama” who, West believed, let black people down. “It is clear,” West said of Coates, that his “narrow ra cial tribalism and myopic political neoliberalism has no place for keeping track of Wall Street greed, US Imperial crimes, or black elite indifference to poverty.” Why, for example, West suggested, should we talk about paying reparations to the descendants of African slaves if the unjust power structures that both fuel and feed off of racism and poverty remain in place and stronger than ever?

cial tribalism and myopic political neoliberalism has no place for keeping track of Wall Street greed, US Imperial crimes, or black elite indifference to poverty.” Why, for example, West suggested, should we talk about paying reparations to the descendants of African slaves if the unjust power structures that both fuel and feed off of racism and poverty remain in place and stronger than ever?

Across the country in recent years, Americans have slowly and haltingly begun to pay more attention to the legacies of slavery. The ugly conservative defense of Confederate monuments can be seen in part as the racists’ reaction to this salutary revisiting of the nation’s past. Exciting scholarship continues to be produced exploring the centrality of slave-holding to the rise of the American republic. Colleges and universities, like Brown and Georgetown and Yale, for instance, as a result of what scholars have learned, have begun to examine critically the importance of slavery in the development of their own institutions, and have tried to set things right. Protestors, young people mostly, have put their bodies on the line to demonstrate to complacent white Americans that “Black Lives Matter.” But look around you, and you will see it: racism is stronger than ever and the rich grow richer and consume an ever-growing piece of the pie.

The past can weigh you down and hold you back. It can sap your strength. Think of people you know. The traumas they have experienced, and the grief and the sadness and the pain they have felt can leave them maimed, scarred, paralyzed, injured. These traumas can become a powerful and important part of their identity, as they see themselves as a victim or a survivor or both. Personal stories and personal histories: our pasts can affect us. What is true for individuals can be true as well for the larger community. Without an accounting the pain remains, the injuries do not heal, and the excuses, justifications, distortions and lies remain unchallenged.

Over the course of the past semester, I have written on this blog about how in a growing number of municipalities and on an increasing number of college campuses commemoration of “Indigenous Peoples’ Day” has either replaced or been appended to celebrations of Columbus Day. On my own campus, a resolution to this effect passed the College Senate unanimously. I have written about efforts in Canada to present the “truth” of what happened in the nation’s residential schools in an effort to find “reconciliation” with Canada’s aboriginal peoples.

There are limits, of course. At the end of the day it costs white people nothing, save for some hurt feelings on the part of conservative snowflakes, to acknowledge Indigenous Peoples’ Day, or to rid themselves of a racist sports team mascot or logo. N othing at all. And, still, it is a slog, every step of the way. Progress, at times, is depressingly slow, the opposition determined. On my own campus, efforts to fly the Haudenosaunee flag on the college flagpole have been defeated by a policy of SUNY leaders in Albany mandating that only the US, the state, the college flag fly. We are located in Geneseo, New York, a town that obviously bears the name of the Seneca village that preceded it on this site. Events of significance, like the Big Tree Treaty of 1797, were supposedly negotiated on the campus grounds. Other significant events–the Sullivan-Clinton campaign marched through town in 1779–occurred nearby. And, of course, there is the people’s history. Long before there was a white settlement at Geneseo, and a Livingston County, long before Continental soldiers burned Iroquois towns and crops in the field and began coveting those lands, the Chenussio Senecas were important actors impossible to miss in the historical record. We are an institution that is part of a state that could not exist in the way it exists without a systematic campaign of Iroquois dispossession. But despite uniform support on my campus, SUNY will not allow our gesture to a shared history and our acknowledgment that the Senecas’ loss was the state’s gain.

othing at all. And, still, it is a slog, every step of the way. Progress, at times, is depressingly slow, the opposition determined. On my own campus, efforts to fly the Haudenosaunee flag on the college flagpole have been defeated by a policy of SUNY leaders in Albany mandating that only the US, the state, the college flag fly. We are located in Geneseo, New York, a town that obviously bears the name of the Seneca village that preceded it on this site. Events of significance, like the Big Tree Treaty of 1797, were supposedly negotiated on the campus grounds. Other significant events–the Sullivan-Clinton campaign marched through town in 1779–occurred nearby. And, of course, there is the people’s history. Long before there was a white settlement at Geneseo, and a Livingston County, long before Continental soldiers burned Iroquois towns and crops in the field and began coveting those lands, the Chenussio Senecas were important actors impossible to miss in the historical record. We are an institution that is part of a state that could not exist in the way it exists without a systematic campaign of Iroquois dispossession. But despite uniform support on my campus, SUNY will not allow our gesture to a shared history and our acknowledgment that the Senecas’ loss was the state’s gain.

So let’s talk truth and let’s talk reconciliation. And let’s do so with an acceptance of the fact that native peoples might stop us and ask, “yes, but upon whose terms?” Talk, after all, our long, shared history shows is exceedingly cheap. Canada and the United States, and their respective provinces and states, and counties, cities and towns, stand on lands that once belonged to native peoples. Sometimes these lands were acquired by white people through means that were illegal and unjust even by the self-justifying standards of the “settler state.” The fact of enduring colonialism is painfully evident. How productive can discussions of reconciliation be without addressing the fundamental reality that settler states rose on native peoples’ land, and that their growth and gain was necessarily native peoples’ loss? How can we fruitfully talk about “reconciliation” when the institutional mechanics of “settler colonialism” remain so thoroughly intact? To get my students to think about these issues I often assign the work of Haudenosaunee scholars like Taiaiake Alfred and Audra Simpson, but there are many other solid people discussing these issues.

West, in a sense, saw Coates tinkering around the edges, offering a powerful critique of white supremacy without a program to tackle fundamental structures of inequality. Whatever one feels about West or Coates, it is a useful debate. I often have students who tell me they “want to do something,” and I admire them for that. I ask them what they have in mind. We talk. They start as reformers, and it can take them time to grasp the larger forces that benefit from and hold in place structural inequality. Similar debates are going on in Native American communities, and we who teach and write in this field need to bring more attention to them. There is plenty of “sympathy” that I hear for what some people still describe as the “plight” of native peoples. Doing something to counter the structural features of “settler colonialism” is another matter indeed, but one that we as scholars and teachers have an obligation to address.