I really admired the work of the historian Calvin Luther Martin. When I was only just beginning my career as a graduate student at Cal State Long Beach in the late 1980s, my adviser directed me to a piece he wrote in The History Teacher, a journal published in the CSULB History Department. It seemed to me an entirely different way of looking at Native American History, one that could free me from the focus on “Indian Policy” that governed much of the historical writing on the subject at the time. Instead of writing about what white people did or did not do to solve a series of “Indian Problems,” Martin focused on Native Peoples themselves, their ways of understanding human and other-than-human beings.At some point I read his Keepers of the Game, and I familiarized myself as well with some of the critiques this award-winning book generated, notably those from the anthropologist J. Shepherd Krech.

As my Master’s thesis neared completion, and I began to seek out Ph.D. programs to which I might apply, I wrote to many historians who were doing what I thought I wanted to do. Though my thesis on the Cherokee Cases bore little resemblance to the work that Martin had done, he responded generously and enthusiastically enough that I sought out an opportunity to meet with him while I visited my parents on the east coast. My folks lived in DC at the time, and Martin, I believe, lived in Baltimore. We met there, and he bought me a very nice lunch. We had a good, and a heavy conversation. I remember feeling out of my league, with a bit of what later might be called “imposter syndrome.” He was super smart. Maybe I was not ready for the big leagues. I cannot remember all that we talked about, but I know I left our conversation with my mind racing, contemplating questions that I had not contemplated before. That’s what we want, right?

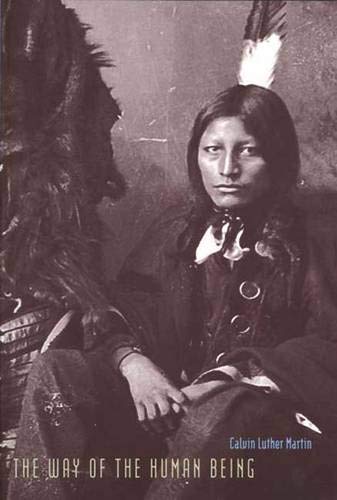

I am not certain if I applied to Rutgers, where Martin taught. If I did, I was either admitted with funding inadequate to allow me to attend, or my application was rejected. I went to Syracuse instead, which paid for everything, and where I also met with a very warm reception. But I kept Martin’s work in mind. A couple of years later, after I started my teaching career at the Montana State University at Billings, and where I first taught significant numbers of Native American students, I wrote to thank him for that meeting, and to tell him how his work informed my courses. And for several years after I arrived in Geneseo, I used his The Way of the Human Being as the first reading in my Native American survey course.

For a time, I loved that book.

Students loved that book.

It moved them.

It moved me.

The Way of the Human Being expanded upon themes present in Martin’s earlier work, but also included an autobiographical tale, of Martin’s own disenchantment with academia and his decision, after spending time teaching in Indigenous communities in Alaska, to leave the college classroom and the historical profession altogether. We historians were, he asserted, asking wrong questions that failed to cut to the vibrant and real heart of Native America.

Somehow I came to know that Martin had moved with his wife to Malone, on the northern edge of the Adirondacks way up in New York’s north country. He may have mentioned that in the preface to The Way of the Human Being. One of my students, who found something in that book that spoke to him in a time of great need, called Martin on the phone, and talked with him for several hours. Some time later I wrote to Martin again. I am pretty sure I thanked him for the book. I know I invited him to come to Geneseo to talk with my students. He very politely declined, explained why he did not do that sort of work anymore, and I believe included a copy of his most recent book, a self-published brief work called The Great Forgetting. I read it in one sitting. I never thought of using it in class, but it did reiterate some of the fundamental ideas of The Way of the Human Being. It was simple, powerful, and showed a breadth of reading that I found invigorating. I appreciated what he had to say in this letter. I was still a fan.

I stopped using The Way of the Human Being several years ago. This saddens me, because I have not found a book that so gently clears the deck, so to speak, and opens the students’ eyes to new ways of thinking and knowing and understanding the relationship between human and other-than-human beings in Indigenous America. If you have read the opening chapter to Native America, you will see me trying to fill that void. I felt I had to abandon the book. Some of the people about whom Martin wrote were made-up. He admitted this in the preface, but still, it gave me pause. Indigenous women, who had served prison time in Alaska, were creatures of his imagination, tragic characters created by a non-native writer to describe the dysfunction and difficulty in a community suffering because it was so out of touch with its core beliefs. This made me deeply uncomfortable. There is a long history, after all, of white writers putting words in the mouths of the Indigenous people they write about. This seemed like too great a blurring of fact and fiction, and it raised for me troubling issues about veracity, accuracy and voice in teaching a class on Native American history to mostly first-year students who had learned virtually nothing accurate about Indigenous peoples at earlier points in their educational careers.

One of the people about whom Martin wrote who unquestionably was real was Sergeant Warren Tanner of the Alaska State Troopers. Martin described Tanner sympathetically, a non-Indian law enforcement officer who dealt with the wreckage that came to a community disconnected from the way of the human being. Tanner was compassionate and wise in Martin’s book. He could not have known that Tanner was not all he seemed to be. Tanner later plead guilty to two counts of sexual abuse committed on a minor. That abuse was taking place during the time that Martin lived in Alaska. I get it. People are complicated. But if some of the most important characters in the book are the fictional creations of the author, or a dangerous pedophile, this presented difficulties that rendered the book more trouble than it was worth. The problems with the book began to outweigh the benefits.

Nonetheless, I continued to read what Martin wrote. Some of the essays he posted on his website I found interesting, even when I did not find his arguments persuasive, and even when I dismissed them as existing on some sort of pseudo-scientific fringe. He wrote frequently, for instance, about the dangers of “Big Wind” and the health consequences that could follow from living close to wind turbines. He and his wife spoke and wrote about Wind Turbine Syndrome. I was not convinced, but I had bigger fish to fry. But recently, after I began subscribing to Martin’s blog posts, I found myself deeply troubled and repelled by Martin’s embrace of anti-vaccine arguments in the midst of a lethal pandemic had has killed more than 620,000 Americans.

IT HAS BEEN A ROUGH EIGHTEEN MONTHS FOR MANY OF US. I understand that millions of people have it worse than me. I have come to accept that I can say this and also say that it has been bad for me, too. My mom, in a rehab facility in March of 2020, suffered a serious stroke at the outset of all this suffering, and the isolation required to combat the virus doubtless limited her prospects for recovery. All of us got sick late last year, the disease likely brought home from one of our kids who worked on the medical front lines in a local hospital. We made it through, but I would not wish Covid on my worst enemy. The pandemic has not hurt us financially, as it has hurt so many others, but otherwise this has been, and remains, difficult. I so want this suffering and madness to end.

Just before I picked up a pencil to being drafting this post, I drove by a crowd of people outside a local strip mall protesting possible vaccine requirements. Vaccines should be a personal choice, the signs said, and these protestors said that they did not want to be unwilling subjects in a corporate medical trial. They were not terribly happy about masks, either. A couple of weeks ago, I was visiting a friend in Long Beach. One of his roommates was not vaccinated. Not putting any of that crap in his body, he said, as he ate shrink-wrapped, grocery store sushi.

I am not an expert on vaccines. I will not claim, as Martin does, to have any expertise in immunology. But I trust the family doctor I have seen for twenty years, and I do know that we live in a country with enough vaccines for everybody, that vaccination has been delayed by unreasoned and emotional opposition, and that this passage of time has allowed the virus to develop new “variants” that are especially contagious. I see no reason to doubt that additional variants are going to develop, and that they could do even more damage. Vaccines, in my view, are not a personal choice. They are an obligation placed on anyone who wants to live in community with others in a civil society. Like the cigarette smokers of the 1980s and 1990s who insisted on their right to smoke anywhere, and the slaveowners who insisted on the right to carry their human property wherever they wanted, Anti-Vaxxers care about nobody but themselves and the small circle of people who share their beliefs. They engage in science-talk and rights-talk to justify what is, in my view, their toxic selfishness. And there are just enough of these lethal fools in this country to ensure that nobody is safe.

I thought it would be chickenshit to write this post without reaching out to Martin. I posted a comment on his website, respecting the request to “please be polite.” I wrote that

“I have respected your work for a very long time. But I have no wish to engage with this turn towards ‘Anti-vax.’ The costs of the past 18 months have been too great, for myself, my family, my friends and neighbors. The decision by too many Americans to not vaccinate has had lethal consequences.”

I told Martin that I was done. I had no wish to read his newsletter any longer. Maybe I was not as polite as I might have been. I will take the blame for that.

Martin’s response came swiftly. He wrote that he refused to “countenance Covid and vaccine fascism, especially when I have graduate credentials (2.5 years at the Ph.D. level) in the subject and I’m married to an MD.” He told me to get as many jabs as I wanted, but said

“don’t lecture me in a subject you know nothing about: that’s offensive and frankly stupid. Call me an anti-vaxxer if you wish; that is, flatten this into epithets. Should I then call you a fascist fool? That gets us nowhere.”

No. It doesn’t.

Martin mentioned that he read the peer-reviewed literature. He asked, rhetorically, if I had read that scholarship and if I could understand it. He mentioned that he was going to delete me from his mailing list, which I appreciated, and said that “it’s time to stand up to people like you who think you’re being virtuous in forcing this insanity on the rest of us.” He closed with eight pointed words: “I find you frightening. Respectfully, we are done.”

Not virtuous, and not frightening. Afraid of getting sick again to be sure. And exhausted by eighteen months of suffering.

I thanked him for taking the time to respond. I acknowledged our disagreement. It was probably a mistake to have replied, for he wasn’t done. He urged me to read the scientific literature. And, he wrote, “don’t think for a moment that you can foist this on the rest of us.” He told me that I am ignorant, that I should keep my ignorance to myself and not “turn it into mandated genocide, which is what this is.”

Like a lot of historians, I like to argue. I like to debate. Like a lot of people, I do not like being insulted. How did I feel at the end of this exchange? Not angry. Not hurt. Just really, really disappointed.

THERE WAS A POINT IN TIME when Calvin Luther Martin wrote books and articles that I valued and from which I learned a great deal. For a time, I loved The Way of the Human Being. Now, he writes words that I find dangerous, hysterical, a little unhinged. I am not certain if I am the only historian who has grown really attached to a book, only to cast it aside after a long reconsideration. Those of you who are historians will remember the job we did in readings courses, where our professors carefully tossed a well-chosen book into the middle of the pit to watch us tear it to shreds. We were hardly sentimental about the work of others. The tone of Martin’s reply to my messages did not bother me. What bothered me was the trajectory he had followed over these many decades. This, as I said above, saddened me. The ideas he expresses now–and I base this on the advice of the medical professionals I know and trust—I believe have actively endangered me, my elderly parents, and my family, including my youngest child, too young still for the vaccine. People change. I know that. Some of us get cranky, forgetful, embittered, or embarrassing. Some of us after searching for so long find ourselves. We come to a place of contentment and calm, with quiet hearts. And some of us cast off the real world altogether. Let us not judge, I tell myself. Respect the burdens people carry, rather than criticize how they carry them. I tell myself this as well. I shake my head. Time to change the channel, I thought. Time to walk away. I am okay with that.