Ethel Daniels was Esther Reed‘s roommate at Mrs. Jacobs’ house between April and August of 1908. Ethel, a Ute from White Rock, had arrived at Carlisle in 1904 when she was twelve years old. She graduated in 1909 and immediately returned home. Mrs. Jacobs’ house was her last outing placement.

Ethel started sending postcards to friends at Carlisle on her way home. She missed the school as soon as she left it. As soon as she got home she reported that she “is enjoying western life” and that her brother Albert “is now a proud father of a cute little boy.”

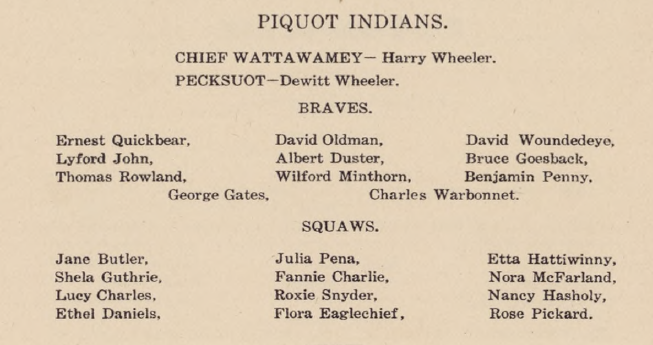

Why share these details of her personal life? Ethel wrote to the school’s superintendent, Moses Friedman, and he would place excerpts of her letters in the Carlisle Arrow, the school’s weekly student newspaper. The Arrow was filled with small pieces of news like this from her and from many other students. At one level these updates served as propaganda–Carlisle graduates were succeeding when they returned home–but it seems to me that this is an explanation that is incomplete and ultimately unsatisfying. Students who returned home wrote back to Carlisle in numbers that at first surprised me, letting people back in Pennsylvania know what they had been up to. Ethel quite clearly loved her time at Carlisle. She said it time and again. So did so many other former students. She was proud, she wrote Friedman, to think that she had been the first president at Carlisle of the “Mercers Literary Society.” In that capacity she practiced her oratory. She was a student in the school’s art department, and was skilled enough as an artist that an Albany businessman purchased a rug that she made. She participated in a musical pageant, “The Captain of Plymouth,” in which she played one of a number of unnamed “Squaws.” Carlisle was an important part of her life.

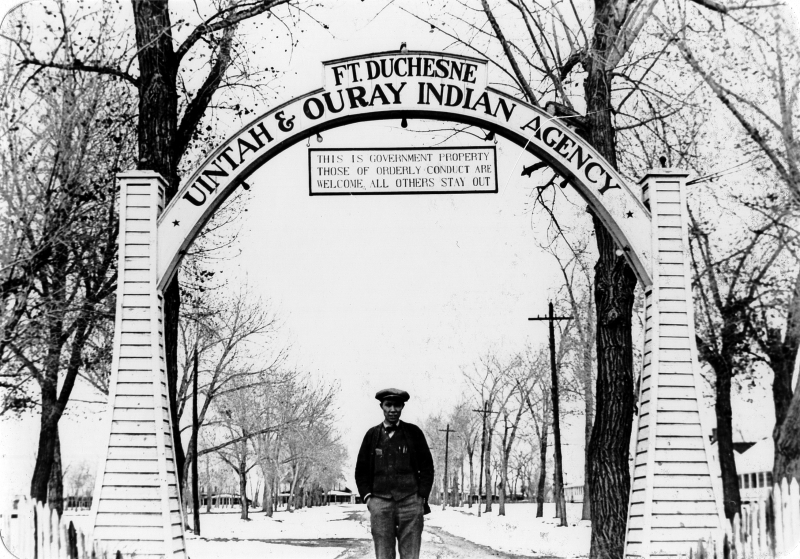

By August of 1910, Ethel was engaged, living on a ranch with her mother, with “forty acres of land, one team, two riding ponies,” and “eleven head of cattle.” She asked that the staff at Carlisle continue to send her copies of The Arrow. She updated students at Carlisle on her family life. She married Donald Cobbs, and soon gave birth to sons named Loyde and Manferd. In 1914, she was living at Fort Duschesne in Utah, and let Superintendent Friedman know that she and the family were well, and that she was “always anxious for the dear Arrow to read the news of dear Old Carlisle.”

She reported in a letter to Friedman that she, Daniel, and the boys were preparing to move to a new allotment. “We have taken another allotment up away from the River bottom,” she wrote. They had bought a new team, after the old team died. “We felt lost with out a team but we just kept courage up, and now we have another team I am glad to say.” Her kids were cute, and she lived near her brother and his family, too. Ranching was hard work but she seemed happy. She reminded Friedman once again to send the Arrow. “It has so many news of how dear old Carlisle is improving.”

Files like Ethel Daniels’ are not uncommon. They do not square easily with the horror stories unearthed at Canadian residential schools, and they do not square easily with the accounts given today of American boarding schools. There is ample evidence of cruelty, neglect, illness and sadness at Carlisle, and we shall get to those stories in the coming segments. But there were also many Indigenous peoples for whom Carlisle provided exciting opportunities, a community of friends, a chance to learn a trade, to perform, to play sports, to make art. Carlisle changed lives, to be sure. Sometimes it devastated, and sometimes it transformed, but it always left a powerful impression on the lives of those who attended.