Della John and Ella Israel were the last two Carlisle girls to pass through Mrs. Jacobs’ House. There is no evidence as to why or what happened to cause her to give up this work. Maybe Mrs. Jacobs got old. Maybe she wanted her summers free, or no longer needed the help the Carlisle girls on outing might provide. She had been at it for more than a decade and a half. It would be an interesting research project indeed to compare Mrs. Jacobs’ work with Carlisle with that of other outing patrons. These patrons have not been studied at all, but they played a role of fundamental importance in the Carlisle students’ lives. They did a great deal of the teaching.

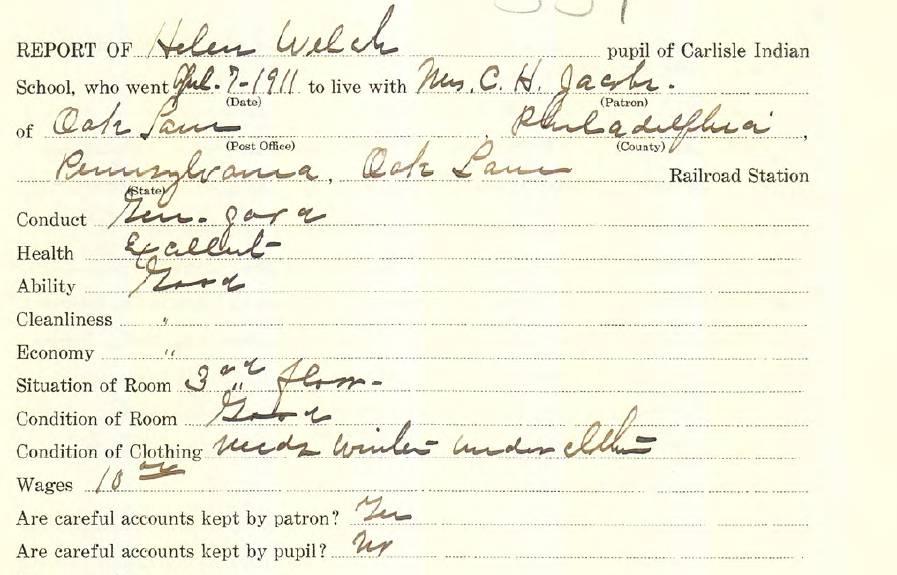

As we wrap up this brief discussion of those young women who passed through the home of Mrs. C. H. Jacobs of Oak Lane, Pennsylvania and Ocean City, New Jersey, it is worth noting that some of the girls who passed through lived lives that are difficult to reconstruct. Dora LaBelle, Francis Halftown, Agnes White, Theresa Brown, and Libby Skye left sparse records from their time at Carlisle. Others, like Helen Welch from Brothertown in Wisconsin, reported familiar themes.

She was doing well, she wrote to Superintendent Moses Friedman after her departure from the school, “but often wish I was back to dear Carlisle.” She left the school because she lacked “a sufficient degree of Indian blood.” She was living in Chicago in 1916, five years after her departure, still writing to the school. Times were tight, and she wondered if there was any money left in her Carlisle account from her outings, including the time she spent at Mrs. Jacobs’ house.

Della and Ella stayed at Mrs. Jacobs’ from the end of May until the beginning of September, 1915. Ella, a Cherokee, was 16 at the time. Della, who came to Carlisle from the Seneca Cattaraugus Reservation, was much older. An orphan, she was 26 years old. She hung around Carlisle after her graduation, continued to attend school during her outings, but did not have much to return home to. She suffered as well from ill health. She had a number of operations during her time at Carlisle, and was plagued by a “nervous disorder” that could be debilitating at times and for which she took medication.

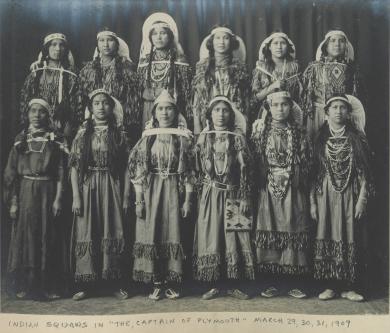

Their time at Carlisle was not dissimilar to that of the other women I have written about in this series of essays. Both Della and Ella were active in the YWCA at Carlisle. Both were members of the Mercers, and both were active in debate. And both Ella and Della, after they left Carlisle, expressed their gratitude for the education they had received and their desire to remain in touch with events back at Carlisle.

I was grading papers as I worked through the final Carlisle files. I am reading drafts of term papers students are writing for my research methods course in Native American history. Two students, in their drafts, felt the need to say something about Carlisle. Both repeated what will be for many a familiar refrain about Carlisle. Students were taken to Carlisle against their will. Once there, they received humiliating haircuts and new names. They suffered from heartache and loneliness at an institution that imposed upon them a soul-crushing American-style education. They were prisoners.

But what the experience of the women who moved through Mrs. Jacobs’ house reveals is that these assumptions—accepted as gospel truth by many students of the Native American past—are not entirely true. Parents sent their children to Carlisle. They wanted for them the education they felt it would provide. The students we have visited with appreciated their time at Carlisle, missed it after they left, and tried to stay in touch with teachers, administrators, and fellow students. It is easy to imagine that the opportunity to learn a trade, to play a sport, to perform in an musical band, and to meet other young people from Native American communities across the country might have been attractive if not exhilarating. Della John’s best friend was a Creek young woman named Tookah McIntosh.

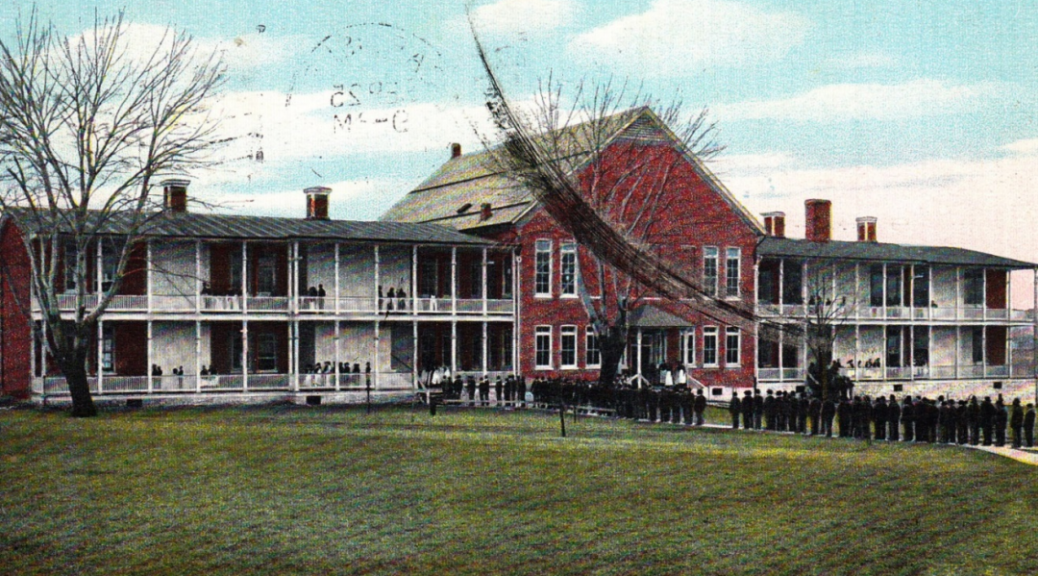

Carlisle opened in 1879. The first of the students I wrote about arrived twenty years later and arrived at Mrs. Jacobs’ house in 1901. Carlisle in its early years was different than in its later years. Record-keeping become more thorough. More and more of the students came from Christian families which had practiced agriculture on the American model. They were literate in English, and they had family names in which they took great pride.

We need to know more about Carlisle, and the boarding school experience in general. There are students who attended Carlisle about whom it is difficult to learn much at all. There are students who are difficult to trace once they left the school. There are so many unanswered questions. But we must be on our toes as historians. We must be willing to be surprised, to admit that our hypotheses are flawed, our accustomed and popular assumptions incorrect, and that what we have been told is wrong. This is an exciting time to be conducting research on boarding schools. The events of the recent past have underscored how fundamentally important and relevant this topic remains, and I am excited to see what happens.