Esther Reed came to Carlisle in 1903 from the Siletz community in Oregon. The Carlisle agents who enrolled her wrote down that her blood was “1/4.” She stayed at Mrs. Jacobs’ house in the Philadelphia suburbs from April until the end of August in 1908. Then she graduated, left Carlisle on the 8th of September, 1908 and headed west. She enrolled at the Chemawa Indian School in Salem, Oregon, now potentially the subject of an federal investigation.

Esther stayed at Chemawa for a only short time, from April until the end of July in 1909. She left likely because she married Joseph A. Dick in 1909 and, she reported to the administrators at Carlisle, things were looking up. “My present home,” she wrote in a questionnaire, “is situated near a large lake called Devil’s Lake and our home is about a mile from the Pacific Ocean.” She and Joseph owned thirty-four acres. They raised horses and cattle, “and we raise all our own grain and vegetables.” She was very happy, she said. Her husband treated her well and, she added, “we have a nice little baby girl about eleven months old and we are very proud of her.”

Esther was a Carlisle booster. Indeed, she wrote to the superintendent asking him to send a Carlisle pennant for her wall. She subscribed to the Carlisle Arrow. She asked for copies of the Carlisle Catalog. She had handed out all her other copies and still had friends who wanted to learn about the school. She wrote to the school’s superintendent in 1916, O. H. Lipps, asking for some blank applications. She hoped her young brother might attend, “as I know it is a fine school.”

Esther never had a chance to visit Carlisle after she left, but she really wanted to go. She had thought about returning to Carlisle in 1912 to attend the school’s commencement ceremonies. But someone had to stay and take care of the farm and the animals. Could not get away from them. And, besides, she wrote, he have had very bad luck.” She told Lipps that the baby girl she was so proud of “took sick and died, which is a very great loss to us.” The girl’s name was Ernestine. After the loss of her child, she continued to work to persuade parents she knew to send their children to Carlisle. The school, and her time there, mattered to her a great deal. Esther loved Carlisle.

I am not sure how much came of her efforts. She may have been the last Siletz to attend Carlisle. She lived in Otis, which was not far from the Siletz community. The idea of Indigenous peoples on the Oregon coast poring through publications from an Indian school two thousand miles away is an arresting one.

I did not follow Esther for the rest of her life. Her brother did not attend Carlisle. I know she liked to sing. She shows up in a quick newspaper search singing at small social gatherings–a friend’s twenty-fifth wedding anniversary, for instance. She was active in civic groups like the Red Cross, and she contributed to war bond drives. She and her husband seem to have done well. They can be seen in the newspapers buying and selling land in western Oregon. I wish I had the time to learn more.

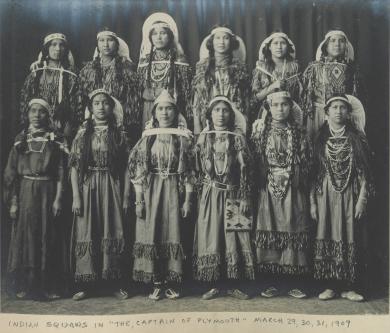

This small picture of Esther Reed, yet another of the girls who stayed with Mrs. Jacobs, once again ought to complicate our image of the Carlisle School. For some, the Carlisle School was undoubtedly a lonely and traumatizing place. For others, like Esther, it was an institution they were proud to have attended, for which they felt great affection, and which they hoped their friends and family might attend. In one of the letters in her small student file, she wrote that she had an opportunity to meet the school’s founder, Col. Richard Henry Pratt. She was delighted that she saw him, “shook hands with him and had quite a talk with him. ” Esther thought “often of Carlisle and my school mates,” she wrote, ” was glad I had the privilege to attend school there.”