California Governor Gavin Newsom has issued an apology for his state’s historic treatment of native peoples. Because one in eight Americans is a Californian by birth or residence, this is a significant act.

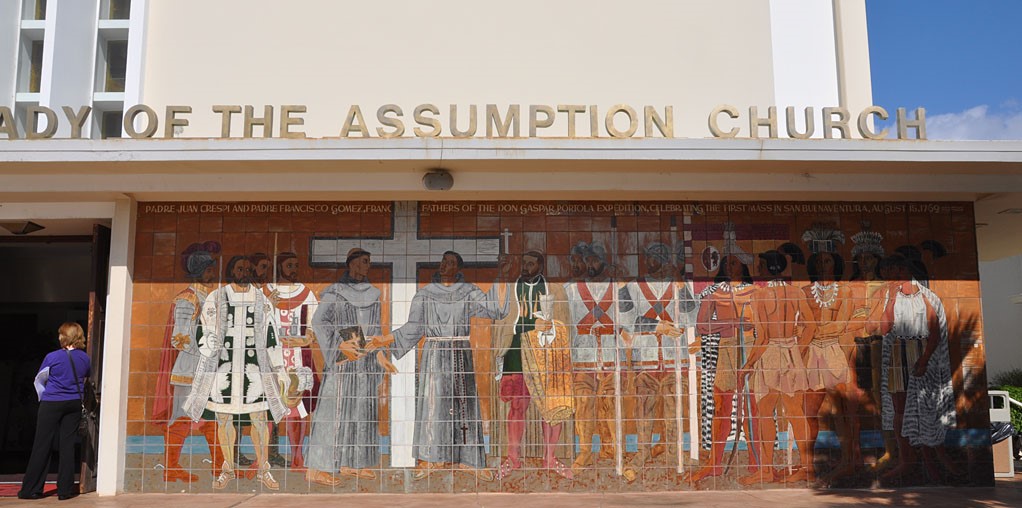

Despite having spent twenty-four of the last twenty-nine years in New York, I still consider myself a Californian. I grew up not far from the Mission San Buenaventura. We traveled almost daily along the route followed by Father Serra as he began his march to establish California’s mission system. At the elementary school I attended we learned a bit about Spanish California. Every time I entered that school parking lot, I passed the mural that you see above, a historic text giving a very biased interpretation of the settlement of Spanish California. We learned in school that their was a series of missions in California, that the missionaries worked hard to establish them, that they were courageous and heroic figures. We learned nothing, however, about native peoples. The junior high schools in town all were named after Spanish explorers. But native peoples simply were not part of the story. The closest any of us got was, perhaps, reading Scott O’Dell’s The Island of the Blue Dolphins or, if we were particularly unfortunate, a staging of the Ramona pageant based upon Helen Hunt Jackson’s dreadful novel. Native Americans, we always were told when I was a kid in the 1970s and 1980s, were all gone.

Governor Newsom has taken an important first step. Apologies alone are seldom enough, but Americans have such a perverse unwillingness to confront their nation’s violent past. You can see this with the reaction to H.R. 40, a proposed piece of legislation that would establish a commission to merely study the possibilities and potential need for reparations for African Americans for centuries of racism. Those of us who teach Native American history are used to receiving a cold response when we suggest repartations (Try it some time. It’s fun! Next time you are at a gathering, try suggesting that the the United States ought to pay reparations to native peoples for the historic injustices they have faced. See how it goes, and report back!).

As Newsom said, what Californians did to Native Americans was a genocide. “No other way to describe it and that’s the way it needs to be described in the history books.” Thanks to the work of historians like Brendan Lindsay and Benjamin Madley, that story is already being told. Newsom’s announcement might have the educational effect of making more Californians aware of their state’s brutal past.

I wrote about California’s native peoples in the second edition of Native America. The entire book is filled with connections to places to which my family and I have connections–the Dakotas in Minnesota, the Crows in Montana, and the Caddos in Texas. And the Chumash in Southern California. I suppose that I am not alone in writing books that, whatever we might say they are about, are at least part of our own story, part of our efforts to make sense of our own past.

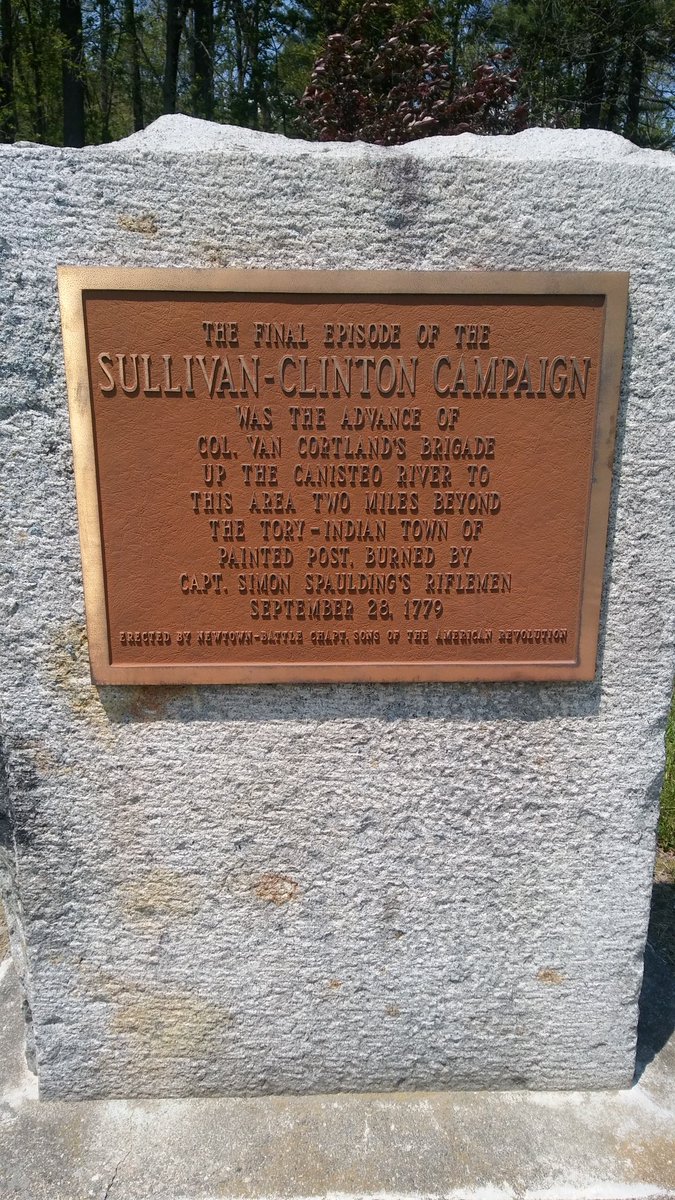

Nearly everywhere I speak, I make the point that nearly all white people in North America are the beneficiaries of specific policies like “Indian Removal”, and the larger generalized processes that resulted in Native American dispossession. The states where I have spent most of my time–New York and California–the country and the continent on which I live, could not have developed in the way that they did without a systematic program of Native American dispossession.

Governor Newsom apologized to California’s native peoples. In person. So many of his predecessors, and their supporters, would have exterminated Native Americans if they could have. Any look at the history books makes clear how hard they tried. An apology is a simple gesture that we often make difficult owing to our fears, our pride, or our lack of empathy. Newsom will take some heat for the apology, but the need for it is crystal clear.