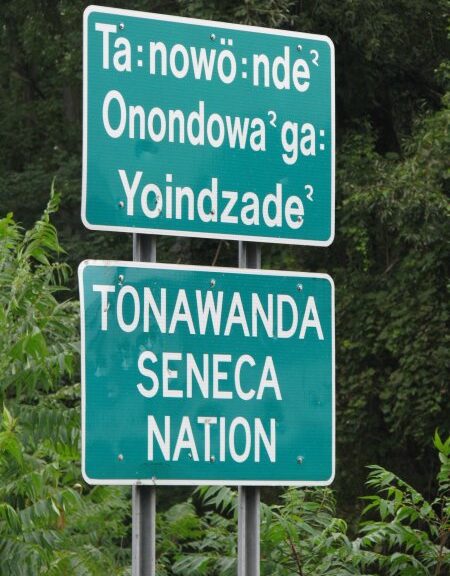

No organization played so energetic a role in the efforts to remove and dispossess the New York Indians as the Ogden Land Company. The Ogden Company’s determination to remove the Seneca Indians would develop into a broader movement to effect the relocation of all the Iroquois from the state, and open their lands to settlement and development. Even as it called for Indian removal, however, the representatives of the Ogden Company recognized that they must pay attention to the requirements of federal law as embodied in the Indian Trade and Intercourse Acts.

I find it troubling that students in New York schools learn about the “Cherokee Removal” in their American history classes, but they hear nothing about efforts to drive the Indigenous people of New York to new homes somewhere in the west. New York’s Indian removals began long before Andrew Jackson became President and continued after he left. It is the story of a conspiracy of interests, as Laurence Hauptman put it, that brought together wealthy businessmen, avaricious politicians, and corruptible federal agents. It is a truly sordid story, and some of it played out in Geneseo where I teach. The Wadsworth family, after whom an important building on campus was named, has mansions on both ends of Main Street. Their money came from Seneca land, and they were in at the ground floor in as Ogden Company investors.

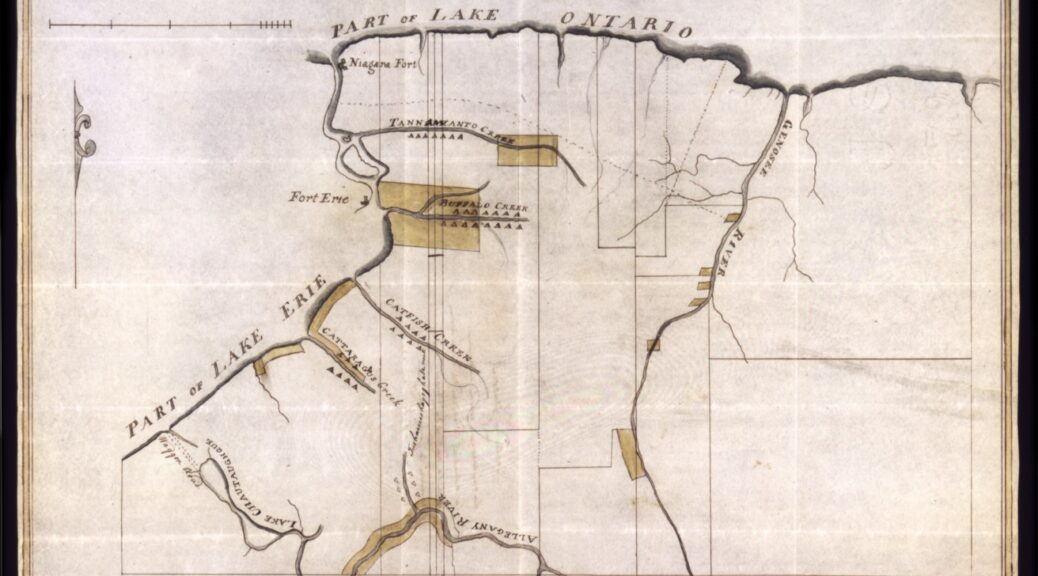

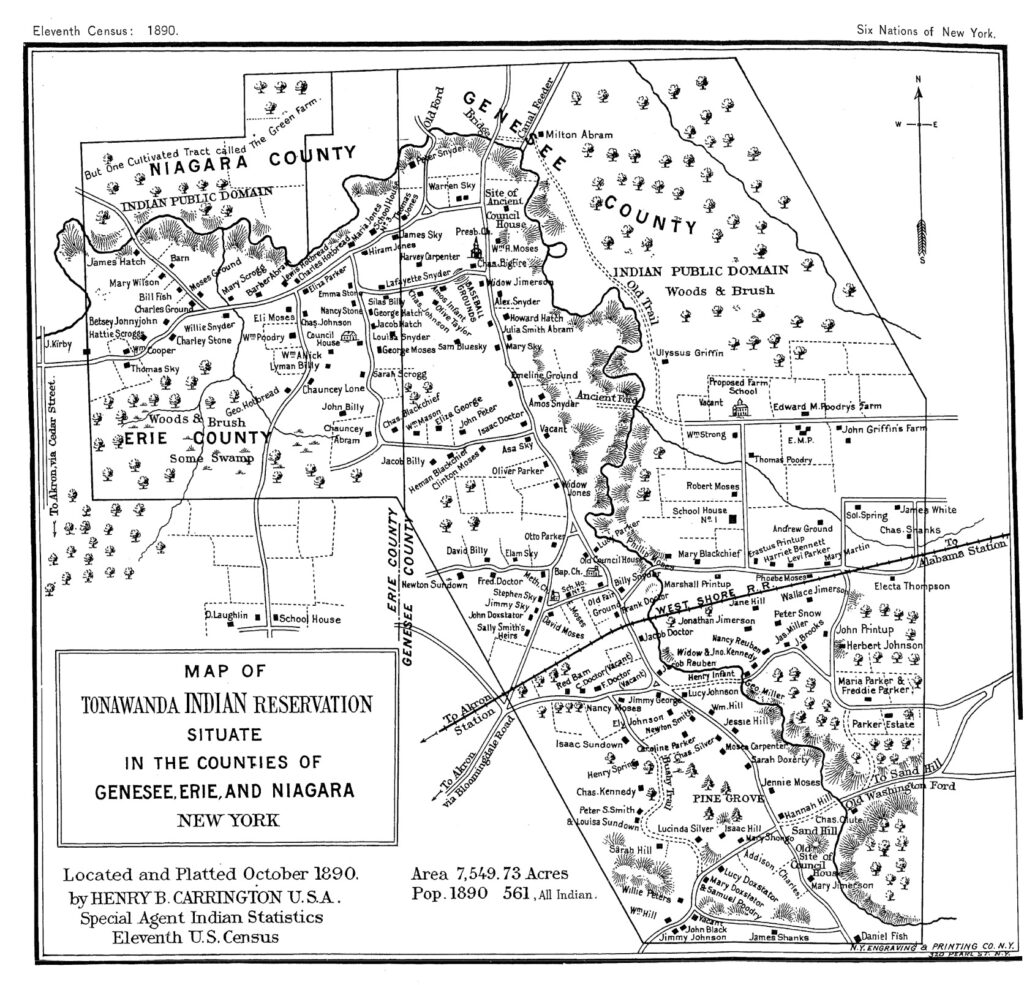

David A. Ogden, the company’s founder and president, purchased from the Holland Land Company in 1810 the pre-emptive rights to the Seneca reservations remaining to the tribe after the Big Tree Treaty of 1797, nearly 200,000 acres for fifty cents an acre. To pay his debt, Ogden created an association of extraordinarily well-connected investors. They moved quickly to exercise that right. They would clear the Senecas out of western New York, gobble up their reservations, and sell the lands to settlers.

Ogden and his associates, it is essential to point out, thoroughly understood the requirements of the Indian Trade and Intercourse Acts, even if they wished the laws were not around to hinder their efforts. This is an important point: determined to drive out the Indians, the Ogden Company officials understood nonetheless that they must comply with federal laws. Robert Troup, one of the Company’s most active members, told the interpreter and federal agent Jasper Parrish in 1810 that the Company, in its attempt to acquire Seneca lands, would “leave everything in the hands of the Agents of the General Government, in full confidence that the Agents will do everything in their power, according to their instructions from the Government, to induce the Indians to accept of a grant of land to the west.” Nothing like friends in high places.

The state of New York provided the Ogden Company with important assistance. In April of 1812, Governor Daniel Tompkins asked Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts “to cause a Superintendent to be appointed” for “holding a treaty with the native Indians for the purchase of their right in a part of the said [Holland Purchase] lands.” Two years later, Tompkins wrote to Secretary of War James Monroe, informing him that the Ogden Company requested the appointment of a federal commissioner. Tompkins told Monroe that “you will perceive that the State of New York is to have no agency in the contemplated treaty, & that the agent or Commissioner requested to be appointed by the United States is wanted for the purpose” of allowing the Ogden Company “to make a legal convention with the Seneca nation of Indians.”

In March of 1818, Ogden told Governor DeWitt Clinton that Seneca opposition to removal resulted from the machinations of “designing men” who opposed his plan. Busy-body missionaries were getting in the way. “The importance of obtaining a seat for our Indians to the west, and to which they may gradually retire,” Ogden wrote, “cannot be doubted.” If Clinton wondered why Ogden was contacting him, the land speculator pointed out “that the interest of the state of New York, in my opinion, is more deeply implicated in the removal of these Indians, than that of any individual interested in the preemption of their lands.” Might as well admit it, Ogden suggested: we all want to drive the Senecas from New York State.

The Ogden Company wanted to remove the Senecas to some location in the west. Troup thought some spot west of the Mississippi, like Arkansas, would be best, but failing that someplace in the northwest, like the Michigan Territory “in the neighborhood of Green Bay,” would do. The Company called upon its allies for help. With Company support, Parrish began the long trip to Washington early in 1817. Once there, he attempted to persuade the new Secretary of War, John C. Calhoun, that removal was in the Indians’ best interest. The Six Nations reservations in the state, Parrish said,

are more or less surrounded by Settlements of whites, in consequence of which there are frequent depredations, petty thefts, and trespasses committed between whites and Indians. Most frequently on the part of the former. It causes the agents considerable time and trouble to settle with and satisfy the injured person, so as to preserve our peace and friendship unbroken. Under these circumstances I think it would be for the interest of the United States, and also for the wellfare and the happiness of the Six Nations could they be persuaded to concentrate themselves.

It is an old story. Local settlers pressed upon Indians and their lands in defiance of the law. Parrish saw removal as a means to protect the Indians from the citizens of the state of New York, who encroached upon their lands, stole their possessions, and threatened the safety of all concerned. We needed to remove the Indians to save them.

The Company’s directors also called upon Lewis Cass, the territorial governor of Michigan, to help remove the Senecas. Cass, in letters to federal agent Erastus Granger and Ogden, expressed a willingness to help, but suggested that if the Company were to succeed, it would need the support of federal officials in Washington. Ogden, as well, asked Peter B. Porter, “one of the greatest promoters of the rise of western New York,” and an associate of the Company, to eliminate the problems caused by two unnamed white men who lived in the vicinity of Buffalo and who counseled the Senecas not to sell their lands. If these men have influence, Ogden suggested, “it might possibly be advisable, to take means to quiet them.”

Ogden painted a bleak picture of the Senecas’ future. The Senecas, Ogden reported, were unwilling to part with any of their lands, and this created a variety of problems. “It has been the wise and constant policy of Government,” Ogden wrote in 1819,

to restrain the Indians from selling or leasing their lands to unauthorized individuals, and hence their reserved tracts remain principally uncleared. The extensive forests operate as a barrier to the progress of improvement. They are not subject to taxation and are made to contribute neither towards the expenses of roads or any other object of public utility. In proportion therefore as they can be withdrawn by proper means from the unprofitable occupation of the Natives and rendered acceptable to cultivation and settlement, they must add to the general prosperity and resources of the State.

The Senecas, he continued, based their resistance on the Canandaigua Treaty, a sophisticated notion that Ogden believed simple-minded Indians could not possibly have arrived at on their own. The Senecas, he believed, incapable of thinking for themselves, had been duped by the deceptions of “designing” white men and those “intent on evangelizing this savage people.”

An appeal to benevolence followed. Removal of the Indians, Ogden argued, certainly would benefit the “Proprietors,” but it also would benefit the Indians. “The History of every Indian tribe on the Atlantic Coast,” Ogden wrote, “proves that they cannot long exist in their savage character in the Neighborhood of civilized Society, that becoming partly Christian, partly Pagan, partly civilized, and partly savage, they are rendered more and more debased and degenerate and finally become extinct, without having rendered themselves capable of any national enjoyment, or having contributed in any degree, to the stock of the public good.” Wiping away his crocodile tears, Ogden’s tone became increasingly urgent, and he hoped that the President would get his point: “The Savage,” Ogden said, “must and ought to yield to the civilized state, and that this change cannot be effected otherwise than by the Agency of the Government.”

Ogden found kindred spirits as well in the New York State Legislature. Indeed, a committee of the New York State legislature reported early in 1819 that concentration was a desirable goal. Alcohol ravaged the Indians, and squatters overran their lands, a problem “highly injurious to the interests of the State.” The conclusion was obvious: it was time for a change in policy. Regarding the Indians, the committee reported

that their independence as a nation ought to cease, that they ought to yield to the public interest, and by a proper application of power they ought to be brought within the pale of civilization and law and if left to themselves will never reach that condition; that such bodies retaining such savage traits ought not to be in an independent condition and that our laws and manners ought to succeed theirs; suitable quantities of lands to be reserved for them.

The State Senate, shortly afterwards, requested that the governor “cooperate with the Government of the United States in such measures . . . to induce the several Indian tribes within this State to concentrate themselves in some suitable situation.” The Senate, however, in a statement that aptly characterized the state’s approach to dealing with its Indians, insisted that the Governor take these actions “either with or without the cooperation of the government of the United States.”

Rhetoric such as this from the New York State Legislature mirrored the arguments occurring at the same time in the southern states, where a states’ rights variant of constitutionalism developed and was nourished in disputes over federal Indian policy. As the federal government and its agents among the Creeks and Cherokees sought to protect the Indians from the aggression of their neighbors, and as missionaries and philanthropists sought their “civilization” and “improvement,” southern state legislatures and southern state courts argued that all who resided within a state, including Indians, must conform to its laws. The Marshall Court, later, would reject this limited federalism, but southerners had the power to largely ignore officials of the national government. The resolution of 1819 shows that New York’s political leaders were developing a similar states’ rights ideology.

After laying all the groundwork, Ogden requested of Secretary of War Calhoun “that a commissioner may be appointed to hold a treaty with all or any of the Tribes composing the Six Nations of Indians residing in this State.” Calhoun appointed Morris Miller to serve as federal agent “in a treaty which the Proprietors of the Seneca Reservation in the State of New York wish to hold with that nation.”

Calhoun believed whole-heartedly in the philanthropic justifications for removal, but at the same time he believed that the practice of treating with Indians was a flawed and dated practice. The national government protected the Indians, Calhoun believed, and “is their best friend.” The Indians depended on the United States like a child relied upon its parents. Calhoun believed that the Indians had not flourished in their homelands, and that they had picked up the vices, but none of the virtues, of the surrounding white population. In this sense, removal seemed to Calhoun a logical solution to the new nation’s “Indian Problem.” If Indians relocated to the western side of the Mississippi River they would distance themselves from the unsavory influence of frontier whites, and gain additional time to become “civilized.” He believed that the United States, rather than the tribes themselves, should decide what was in the Indians’ best interest. He hoped that they would see the value of removal; at the same time, Calhoun believed strongly that removal could not be forced and that under law, the United States must oversee the process of Indian land sales. At least as long as it was convenient to do so.

Aware that they had the support of the federal government, the Ogden associates played their cards carefully. The object was limited: concentrate the Senecas at Allegany, and open their other lands to white settlement. The best thing the Company could do, William Troup told Jasper Parrish, is “to be perfectly still, and to make no appearance whatever” at the Council, and “to leave everything entirely in the hands of the Commissioners of the General Government, in full confidence that the Agents will do every thing in their power, according to their instructions from the government, to induce the Indians to accept of a grant of land to the West.”

Morris Miller, the United States agent, did try to persuade the Senecas to remove. He claimed to have the best interests of the Indians at heart. He told the Senecas that “I am not in any way instructed, pledged or interested to promote the views of the white men, where these views are prejudiciall to the rights of the red men.” Nonetheless, Morris’s boss, the Indians’ “Great Father,”

sees you scattered here and there, in small parcels everywhere, surrounded by white people. He sees that you are fast losing your national character, and are daily more and more exposed to the bad examples of your white Brothers, without the restraint of their laws and religion. He sees that this frequent and uncontrolled intercourse, instead of doing good is doing injury to you and to them. Your great Father sees all these things, with grief and concern. He lays them much to heart; and thinks it impossible for you, under such circumstances, to retain the character of an independent nation.

The Great Father looked after his white children as well, Morris continued, and from them he heard of their dissatisfaction

at seeing the lands in your occupation remain wild and uncultivated; neither paying taxes, nor assisting to make roads and other improvements; nor in any way contributing to the public burthens, as white peoples’ lands do. Your Great Father has been further informed that you occupy more land than you can advantageously till, or use for any valuable purpose; whilst at this same time the scarcity of game prevents your engaging in those pursuits, to which your fathers were accustomed.

The solution was simple. The President, Morris told the Senecas, desires “that you should live at a greater distance from white people, so that you may be more secure in the enjoyment of your property. And that he can with greater convenience, and less expense cause you to be instructed in agriculture, and the useful arts; and your children to be taught to read and write, and that your nation may thus be rendered an industrious and happy people.”

The Senecas, divided among traditionalists and those more willing to selectively adopt elements of white culture, rallied together to oppose cessions of Seneca land. Quaker missionaries, too, supported the Senecas. The Quakers argued that concentration at Allegheny would undermine the Friends’ efforts to Christianize and civilize the Senecas at Buffalo Creek, and that there was not an adequate supply of land at Allegheny to support all the Senecas. The Quakers, in fact, long had opposed the Ogden Company’s agenda. In 1817, for instance, the Society of Friends delivered a message “to the Chiefs and other Indians on the Allegany Reservation,” advising them that “the land on which you live is your own—and you know it to be good and some of it well-improved . . . It cannot be taken from you without your consent.”

Timothy Pickering advised the Quakers on methods to help the Senecas hang on to their lands. “Knowing as I do,” he wrote,

the rapacity of some men among the Whites, I am not surprised at the attempts to seduce the Chiefs to sell the seats from under themselves, and their people. It is in the power of the government to defeat these attempts. But artful men may apply to it for the appointment of a commissioner to hold a treaty, and by false but plausible representations, and perhaps, too, aided by certificates of men apparently disinterested, obtain this request.

Pickering suggested to the Quakers that they have “the chiefs and all their people assemble in council, and enter into an agreement, never to sell their lands, or any part of them, without the assent of the warriors or grown men, as well as of the chiefs.” Further, Pickering reminded the Quakers that “by laws enacted from the year 1790 to 1802, no purchase of Indians’ land are valid, unless made at a treaty held under the authority of the United States.” Pickering’s statement shows that he understood that the federal government had a responsibility to protect Indian land from territorially aggressive interests in the states, and that stopping these forces, even with the support of the laws of the national government, would not be an easy task.

Led by Red Jacket, the Senecas refused to sell to the Ogden Company in 1819, and their rejection “was so unqualified and so peremptory, as to forbid all reasonable expectation that any good purpose could be effected by adjourning the council,” Miller wrote, and so “it was therefore finally closed.”

There can be no question that the United States gave aid and encouragement to the Ogden Land Company, those “artful men” so determined to acquire Seneca land in western New York. The important point for our purposes, however, is that however reprehensible the practices of the Company, it recognized the rules of the game as spelled out in the Indian Trade and Intercourse Acts, and actively requested the involvement of the United States to ensure the legality of its purchases. It is unfortunate that New York State did not exercise the same due diligence.