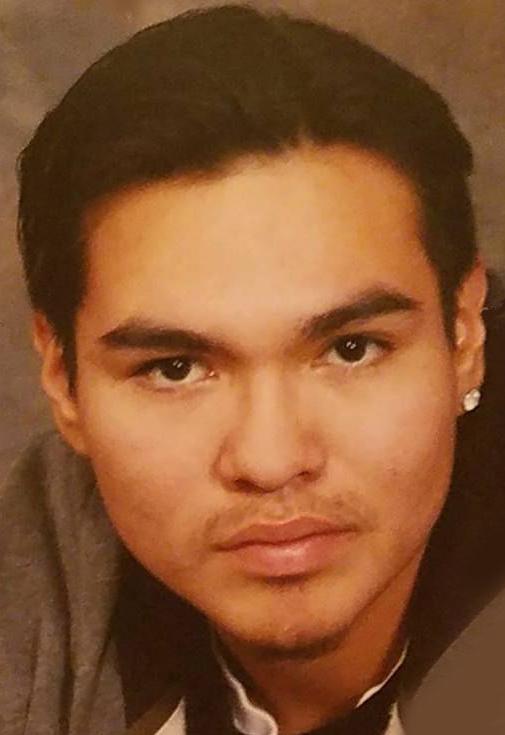

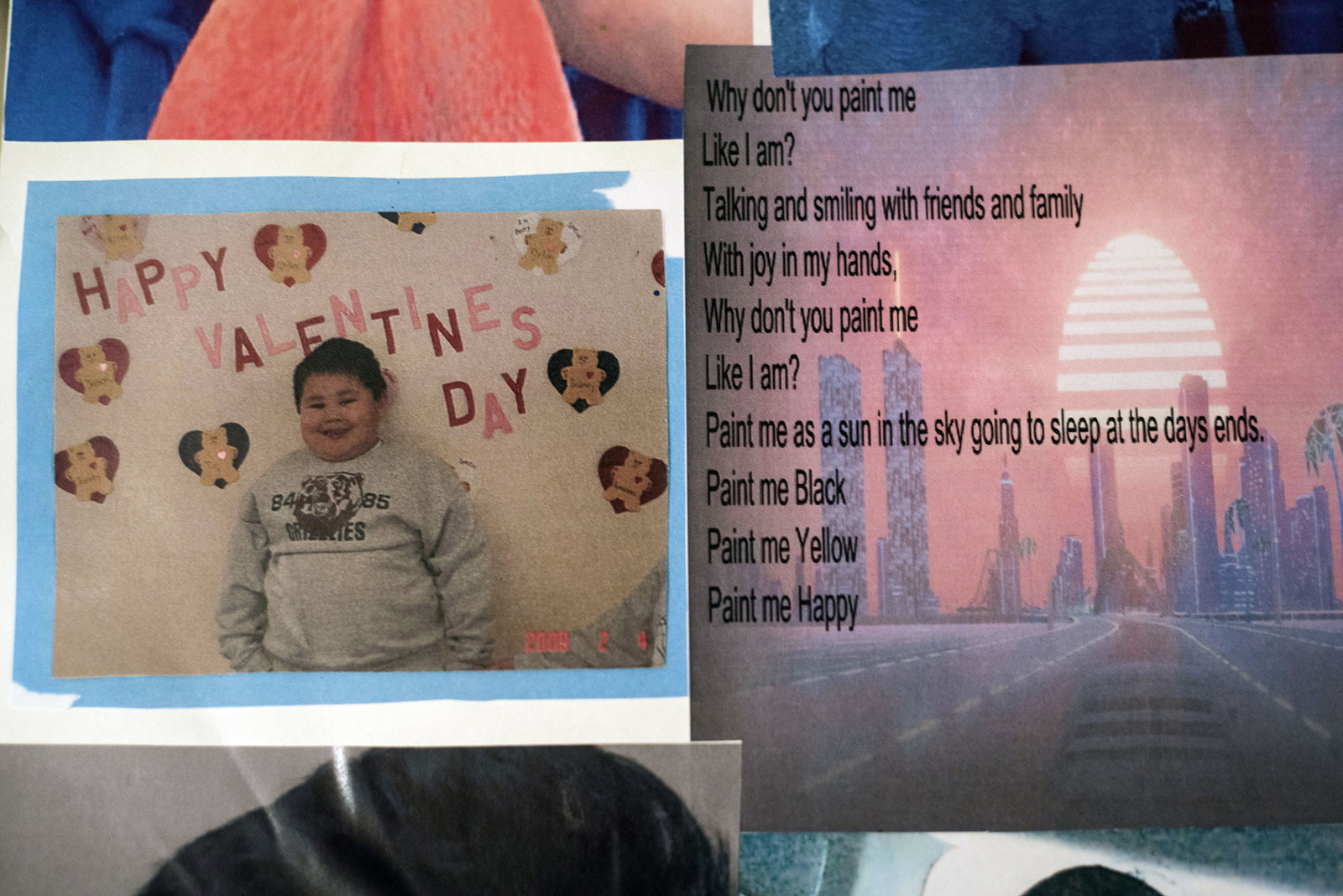

Two important stories came across the line yesterday, and those of us who teach Native American history need to do a better job of following them. On June 5, police officers killed Zachary Bearheels, a twenty-nine year old man with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Bearheels was punched in the head and shocked by a taser several times. Omaha police have admitted that the officers’ conduct was a violation of departmental policy and that two of the officers involved would be terminated.

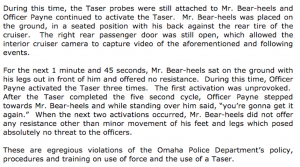

According to the story reported on the Indian Country Today Media Network, Bearheels had been traveling from South Dakota to Oklahoma City aboard a bus. After a passenger complained about his conduct, he was kicked off and left stranded in Omaha. Bearheels was behaving in a manner that police were called by witnesses. He was attacked and abused by the police. Witnesses, and the internal reports of the Omaha Police Department, both indicated that Bearheels posed no threat and that the violence was entirely unjustified, and “egregious violations of the Omaha Police Department’s policy procedures and training on the use of force and the use of a taser.”

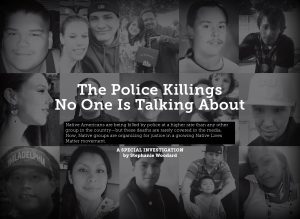

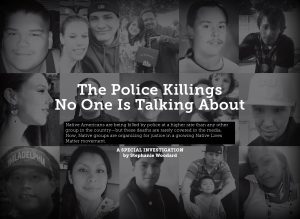

Bearheels’ death at the hands  of the Omaha Police is one more example of the larger problem reported in a story looking at “The Police Killings No One is Talking About” that appeared In These Times. The story was written by Stephanie Woodard, and the evidence she presents is harrowing. Police killed twenty-one Native Americans in 2016, up from 15 in 2014. According to a 2014 study from the Center for Juvenile and Criminal Justice, Native Americans are more likely to be killed by police than any other demographic in the United States. Native Americans are 3.1 times more likely to be killed by the police than white Americans.

of the Omaha Police is one more example of the larger problem reported in a story looking at “The Police Killings No One is Talking About” that appeared In These Times. The story was written by Stephanie Woodard, and the evidence she presents is harrowing. Police killed twenty-one Native Americans in 2016, up from 15 in 2014. According to a 2014 study from the Center for Juvenile and Criminal Justice, Native Americans are more likely to be killed by police than any other demographic in the United States. Native Americans are 3.1 times more likely to be killed by the police than white Americans.

Joseph Murphy, for example, a thirty-three year old veteran of the Iraq War: He died of a heart attack in a holding cell in a Juneau jail. He had called for help, but guards yelled “Fuck You” and “I don’t care” in response to his pleas for medical assistance. Others were shot sitting in cars, or while holding knives, or while distraught and unwilling to listen to police demands that they comply. In nearly every case, the homicides were ruled justifiable.

And the parallels to what we have witnessed in the African-American community are clear. Many reservation border towns are rife with racism and discrimination against native peoples. I saw this first hand in Hardin, where I attempted to conduct interviews nearly twenty years ago. I had heard some of my Crow students describe the racism they faced at Hardin High School. I wanted to get at relations between the Crows and their white neighbors. I was not able to immerse myself in the community deep enough to get white people to talk to me, but the problems were not hard to see there. And in Billings, sixty miles from Crow, where I lived, and where native peoples were a despised and unwelcome minority. Expressions of racism towards native peoples were, to me, shockingly common and public.

I have spent a large part of my career, in a sense, writing about white violence against native peoples. In my first book, I looked at the violence of the Anglo-American frontier, and the sources of the racial antipathy that took route there . I wrote about the race wars pitting native peoples against land-hungry settlers in New England and the Chesapeake in the seventeenth centuries. I wrote about the murder of an Algonquian weroance near Roanoke Island in 1586, and the consequences of that violent act. In my relatively recent book on Canandaigua, I wrote about the violence on the Pennsylvania and New York frontier, where the unpunished murder of Senecas by frontier whites served as one of the major grievances American officials and Haudenosaunee diplomats needed to address. I could teach my courses in Native American history focusing on acts of violence every day if I wished, from Roanoke to Jamestown, to Marblehead to the Lancaster Workhouse to Gnaddenhutten and Sand Creek, from Wounded Knee to Omaha and border towns throughout Native America where, too often, law enforcement officers are ending the lives of native peoples. It is an old, old story, this, and it needs to stop.

Black Lives Matter has brought massive attention to the slaughter of African Americans at the hands of police. The entire Black Lives Matter movement has done such important work in focusing attention on racism and discrimination and violence perpetrated by police against African Americans. At the same time, as Woodard points out, “a larger narrative is at play: racial issues in the United States tend to be framed as black and whites, while other groups are ignored.”

I plan on assigning Woodard’s piece when I teach my Indian law class again next spring, and spend some time on this issue. Students come to college inclined to think of native peoples as being part of the past. Their understanding of civil rights and discrimination and race relations is, as Woodard points out, too often limited to thinking in terms of matters black and white. They can only benefit by reading closely these powerful stories, and learning that the police, in all too many instances, are viewed as a threat by the people they are supposed to protect and serve.