Peter Feinman does important work promoting the study of New York history. It is important to give him his due. That said, a number of recent posts on his blog touching upon subjects relevant to Native American history struck me as particularly disappointing.

Over the past couple of weeks, Feinman has offered his thoughts on the Columbus Day/Indigenous Peoples’ Day controversy. As many readers will no doubt recognize, a growing number of states, municipalities, and other organizations have replaced their celebration of Columbus Day with recognition of Indigenous Peoples’ Day. Drawing upon the language used in newspaper coverage, Feinman sees this process as insufficiently respectful. Columbus Day has not been replaced by Indigenous Peoples’ Day. No. It has been “dumped” and “ditched.” In the second installment, posted on May 30 and available here, Feinman describes the origins of America’s reverence for Columbus in myth, memory, and history. There is some useful information here. Feinman argues that “the issue of Columbus is very much connected to the culture wars that are currently dividing America.”

You almost get the impression that if Columbus had not sailed the ocean blue in 1492 that Europeans, smallpox, and genocide would never have occurred and that the United States would not even exist as a country, since there would have been no one here to declare independence from England.

There is in Feinman’s post the familiar expression of concerns about matters “politically correct.” For instance, Feinman writes that “just as it is now illegal to dance to the music of Michael Jackson, laugh at a joke by Woody Allen, or watch anything involving a #MeToo person,” so “Columbus is to be cleansed from our midst.” The message these efforts send, Feinman says, is that “it is incumbent on Americans to purify the country of its sins and the stains on the social fabric.” If you read my blog with any regularity, you know I find these arguments unpersuasive. To call something “politically correct,” it seems to me, is the intellectual equivalent of calling someone a Communist in the 1950s. It is an indication that you are not interested in debate and, too often, that you are uninterested in talking about the historical experience of peoples on the margins.

In the third installment, Feinman objects to uncritical use of the word “indigenous,” which he believes has conveyed “the message that there is a global people called Indigenous as if they are a single people.”

When I was growing up I don’t recall hearing the word ‘indigenous’ often. Peoples usually had real names. Sometimes they were their own names, sometimes they were the names other applied to them–Indians, Asians, Egyptians, etc. Now these Eurocentric names are to be banished from polite conversation. People are to be referred to as indigenous no matter where they are in the world. The word “Indigenous” has been weaponized by some white Americans in the culture wars against other white Americans, and imposed on people who had names for themselves and never used the word “Indigenous.” The result is a simpleminded, superficial, bogus term that produces strange results when removed from the American context that created it. Why did the politically correct unleash this weapon?

Uncritical language use is maddening. But I do not believe that this is as big a problem as Feinman says it is. “Indigenous:” the word is commonly used, as Feinman says, but its application is hardly mysterious and hardly mystifying. Its application to native peoples countering “settler colonialism” or good ol’ fashioned imperialism is a salutary development. And look at the language in Feinman’s post. There is talk of weapons unleashed, of prohibition and proscription, of banishment and censorship. I disagree with a lot of this. This is the language of a culture war, indeed. But as a white guy who has taught Native American history for a quarter-century, I have never felt the limitations that seem to run through what Feinman has to say here. I have had debates with many, arguments with others. But that is part of the game. The past is contested, and that includes the language we use to describe it. It is not a war. It is what we do.

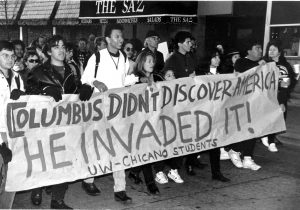

I have written about Columbus Day and Indigenous Peoples’ Day in the past. As I wrote back in October of 2017, “in Native American history, there are lots of guilty parties, but Christopher Columbus is guiltier than most.” Columbus gets both more credit and more criticism than he deserves as an individual. That said, “there is absolutely nothing edifying in this story of avarice, violence, and religious bigotry, save for the native peoples who at times and places survived the carnage,” and “the continued celebration of Columbus Day does a historical injustice to the native peoples of two continents and the Caribbean.” Nothing Feinman wrote convinced me to change my mind on this matter.

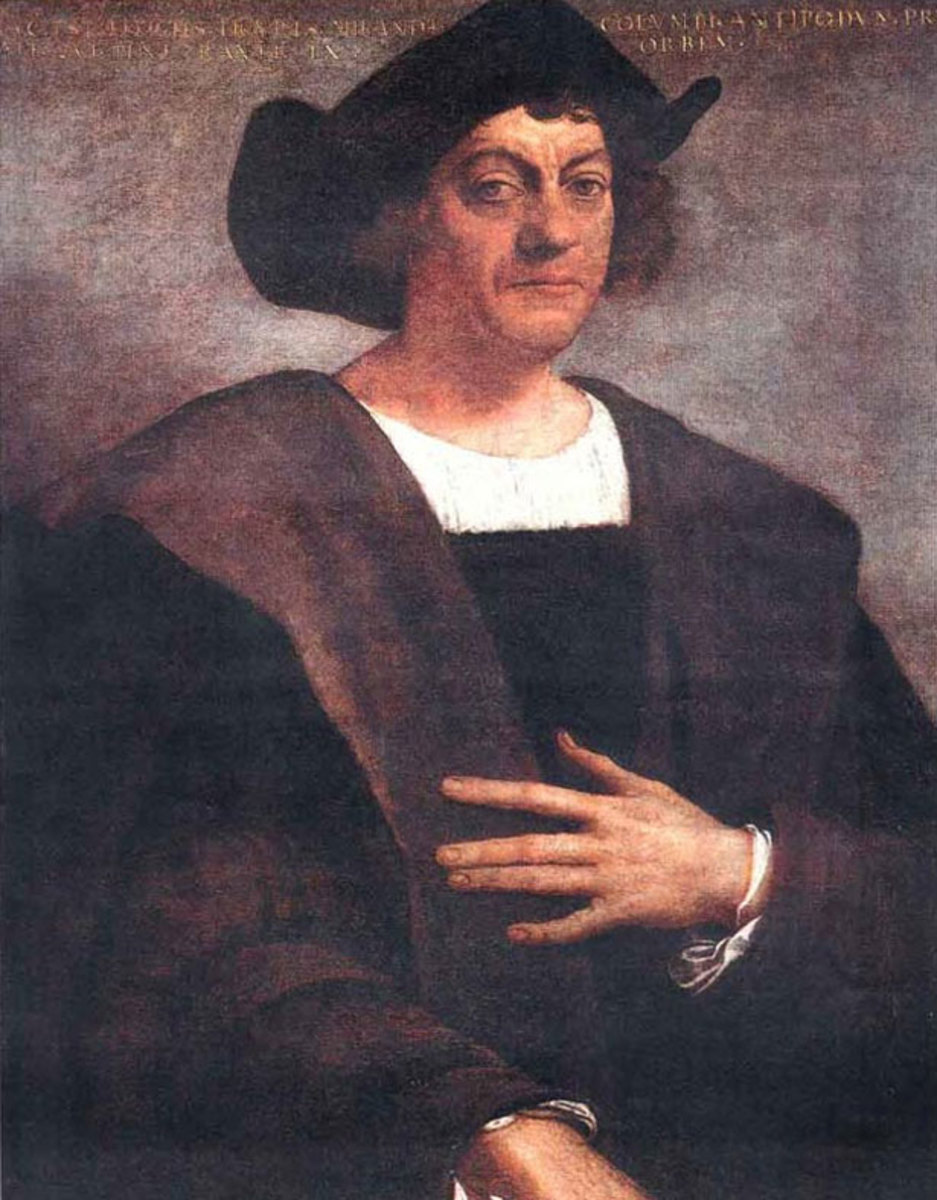

Feinman says much of value about the origins of Columbus Day. He is absolutely correct in pointing out Americans’ uncritical reverence for Columbus, and he provides some interesting examples. Columbus always has been a symbol. He remain a symbol today. The Columbian Encounter, so-called, is the beginning of a horror story for the native peoples of the Americas, North, South, and Central, as well as the indigenous population of the Caribbean, who were quickly destroyed as autonomous peoples by the Spanish newcomers. Columbus, his supporters might argue, gets too much of the blame. He did nothing to native peoples in North America because he never set foot on the North American continent. This much is true, but Columbus has become, and perhaps always has been, a symbol standing in for the “fundamental violence of discovery,” as I class it in the second chapter of Native America. Between the first and second editions of the textbook, one of the many books I read as I worked on revising was Andres Resendez’s excellent The Other Slavery which, among other things, described in detail the centrality of slavery in Columbus’s enterprise. Columbus carried slaves back to Spain on each of his voyages, and promised the Crown “as many slaves as Their Majesties orders to make.”

Holidays come, and holidays go. Ask any historian. She will tell you that. Commemorating Indigenous Peoples’ Day does not belittle or demean the western tradition. What it does do is allow us to pay attention to the experience of those native peoples whose losses were Europeans’ gain, and who have endured and survived through five centuries of discrimination, dispossession, and slaughter. If, after all, any number of people in our nation’s history had had their way, native peoples would be gone: They would have been wiped out by warfare and epidemic and chronic disease; or they would have been “removed” to make way for the “settlers” who championed the rise of Andrew Jackson in the first few decades of the nineteenth century; or confined on tiny reservations until the missionaries and teachers and government farmers wiped away any trace of their identity as native peoples; or assimilated into the American body politic; or “terminated” in the middle decades of the twentieth century, with the reality of their native nations erased by congressional statute. Indians were supposed to disappear. If any number of people had their way, Native American people would not be here to call for an Indigenous Peoples’ Day.

Columbus Day found its origins in discrimination against Italian-American immigrants. We were here from the beginning, Italian-Americans said, and we have as great a claim to this continent as any other group. The holiday has seldom encouraged any significant and honest discussion of the consequences of the Columbian Encounter, a process which was, as historian Alfred Crosby showed a long time ago, much bigger than Christopher Columbus. It is time for the bad history and the myth associated with this day to go away, and if recognizing Indigenous Peoples’ Day helps I am all for it. Let’s talk about Columbus, to be sure, and the European invasion of America, but let’s do so with our eyes firmly upon those native peoples whose losses were Europeans’ gain, and who have endured and survived through five centuries of discrimination, dispossession, and slaughter.