In Native American history, there are lots of guilty parties, but Christopher Columbus is guiltier than most. There is absolutely nothing edifying in this story of avarice, violence, and religious bigotry, save for the native peoples who at times and places survived the carnage. The continued celebration of Columbus Day does a historical injustice to the native peoples of two continents and the Caribbean.

The Columbus Day holiday found its origins in the Italian-American community. Columbus, quite likely from Genoa, sailed in the service of Ferdinand and Isabella, the authors of the Spanish Reconquista, and in 1492 he “discovered” America. He was, his advocates claim, an Italian and an American hero. The holiday in his honor asserted that Italians were Americans, too.

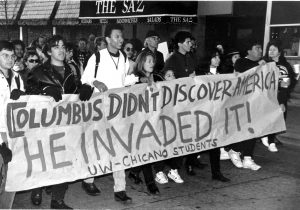

But the Columbus Day holiday has been under siege for some time. He discovered nothing, of course, for the “New World” he stumbled across in search of the riches of Cathay was already occupied by millions of people. The 500th anniversary of Columbus’s voyages in 1992 reawakened interest in the explorer and his actions in the New World, and that attention did not cast Columbus in a good light. Recently, a growing number of colleges and municipalities across the country have recognized Indigenous Peoples’ Day, to be held on the federal Columbus Day holiday. An Italian-American friend of mine asked me the other night why any one of the other 364 days of the year could not be chosen for Indigenous Peoples Day. In his view, the movement to obtain recognition for Indigenous Peoples’ Day generated conflict where none was needed, and caused offense to Italian-Americans. While I understand his argument, the  commemoration of Indigenous Peoples Day is something I support. As I point out in Native America, the Columbus Day holiday “many native peoples view as a day for mourning the victims of an American holocaust and 500 years of genocide.”

commemoration of Indigenous Peoples Day is something I support. As I point out in Native America, the Columbus Day holiday “many native peoples view as a day for mourning the victims of an American holocaust and 500 years of genocide.”

The Columbian Encounter, so-called, is the beginning of a horror story for the native peoples of the Americas, North, South, and Central, as well as the indigenous population of the Caribbean, who were quickly destroyed as autonomous peoples by the Spanish newcomers. Columbus, his supporters might argue, gets too much of the blame. He did nothing to native peoples  in North America because he never set foot on the North American continent. This much is true, but Columbus has become, and perhaps always has been, a symbol standing in for the “fundamental violence of discovery,” as I class it in the second chapter of Native America.

in North America because he never set foot on the North American continent. This much is true, but Columbus has become, and perhaps always has been, a symbol standing in for the “fundamental violence of discovery,” as I class it in the second chapter of Native America.

Long ago I taught at a one-day NEH gathering on the Blackfeet Reservation way up in northwestern Montana. The subject was children’s literature that treated in different ways the history of America’s native peoples. One of the books was Michael Dorris’s Morning Girl (1992). The story followed Morning Girl and her brother Star Boy, indigenous children playing and exploring in the “Pre-Columbian” Caribbean. It is a story that is wise and gentle. But at its close, it takes a darker turn. Morning Girl swims out to see a strange sight approaching the beach.

Dorris ends the story with a lengthy excerpt from Columbus’s journal:

In order that they would be friendly to us — because I recognized that they were people who would be better freed and converted to our Holy Faith by love than by force — to some of them I gave red caps, and glass beads which they put on their chests, and many other things of small value, in which they took so much pleasure and became so much our friends that it was a marvel. Later they came swimming to the ships’ launches where we were and brought us parrots and cotton thread in balls and javelins and many other things, and they traded them to us for other things which we gave them, such as small glass beads and bells. In sum, they took everything and gave of what they had very willingly. But it seemed to me that they were a people very poor in everything. All of them go around as naked as their mothers bore them; and the women also, although I did not see more than one quite young girl. And all those that I saw were young people, for none did I see of more than 30 years of age. They are very well formed, with handsome bodies and good faces. Their hair coarse — almost like the tail of a horse-and short. They wear their hair down over their eyebrows except for a little in the back which they wear long and never cut. Some of them paint themselves with black, and they are of the color of the Canarians, neither black nor white; and some of them paint themselves with white, and some of them with red, and some of them with whatever they find. And some of them paint their faces, and some of them the whole body, and some of them only the eyes, and some of them only the nose. They do not carry arms nor

are they acquainted with them, because I showed them swords and they took them by the edge and through ignorance cut themselves. They have no iron.

Their javelins are shafts without iron and some of them have at the end a fish tooth…. All of them alike are of good-sized stature and carry themselves well. I saw some who had marks of wounds on their bodies and I made signs to them asking what they were; and they showed me how people from other islands nearby came there and tried to take them, and how they defended themselves; and I believed and believe that — they come here from tierrafirme to take them captive. They should be good and intelligent servants, for I see that they say very quickly everything that is said to them; and I believe that they would become Christians very easily, for it seemed to me that they had no religion. Our Lord pleasing, at the time of my departure I will take six of them from here to Your Highnesses in order that they may learn to speak…

Morning Girl, then, is the story of that child who Columbus saw as his men approached landfall in October of 1492, and whose gentleness and innocence led the wayward Admiral to conclude that her people would make good servants.

We spent quite a bit of time that morning discussing Dorris’s book. The teachers from Blackfeet felt very differently about the book than did some of the non-native teachers. The Blackfeet teachers all agreed that if they were to use Morning Girl in class, they would cut out that last piece. They would have physically removed the last page from the book. Too painful, and too traumatic for the children who might read it, they thought. In Fourteen-Hundred and Ninety-Two, Columbus sailed the ocean blue…and contemplated how indigenous children might make good slaves.

I do not agree with altering books in this manner, nor in insulating children from the more horrifying parts of our shared history, but I understood their concerns. I spend some time on Columbus in Native America. I have to. Between the first and second editions, one of the many books I read as I worked on revising the text was Andres Resendez’s excellent The Other Slavery which, among other things, described in detail the centrality of slavery in Columbus’s enterprise. Columbus carried slaves back to Spain on each of his voyages, and promised the Crown “as many slaves as Their Majesties orders to make.”

If you read excerpts from Bartolome De Las Casas’s Devastation of the Indies–and if you are a student in a Native American history course treating this period you likely will–you can read about the sheer brutality of the Spanish conquistadors who followed Columbus. Las Casas provides a first-hand account of the first modern genocide: Spanish ships able to sail homeward without need of navigational instruments because all they needed to do was follow the trail of floating corpses, enslaved Indians who died on the Atlantic crossing. Las Casas described how Spanish colonists could buy human flesh for their dogs, and how Spanish war dogs tore native peoples literally limb from limb. Las Casas described the competition between conquistadors to see who could run through the most Indians with one thrust of the pike, and how Spaniards burned native peoples in groups of thirteen in honor of Jesus and the apostles, and bashed their children’s heads in by swinging them against the rocks, as in the Flemish (and Protestant) engraving to the left. And all this brutality, all the subjugation that occurred under the aegis of the Spanish encomienda system, exacerbated the consequences of epidemic diseases, which in places killed off 80% of the population. Brutality made native peoples less able to resist the onslaught of disease. Millions died.

If you read excerpts from Bartolome De Las Casas’s Devastation of the Indies–and if you are a student in a Native American history course treating this period you likely will–you can read about the sheer brutality of the Spanish conquistadors who followed Columbus. Las Casas provides a first-hand account of the first modern genocide: Spanish ships able to sail homeward without need of navigational instruments because all they needed to do was follow the trail of floating corpses, enslaved Indians who died on the Atlantic crossing. Las Casas described how Spanish colonists could buy human flesh for their dogs, and how Spanish war dogs tore native peoples literally limb from limb. Las Casas described the competition between conquistadors to see who could run through the most Indians with one thrust of the pike, and how Spaniards burned native peoples in groups of thirteen in honor of Jesus and the apostles, and bashed their children’s heads in by swinging them against the rocks, as in the Flemish (and Protestant) engraving to the left. And all this brutality, all the subjugation that occurred under the aegis of the Spanish encomienda system, exacerbated the consequences of epidemic diseases, which in places killed off 80% of the population. Brutality made native peoples less able to resist the onslaught of disease. Millions died.

But here’s the thing, and I hope you will see it if you read Native America. We can focus on victimization and cruelty. God knows, Columbus and his successors were violent and brutal and victimized many. But to focus on victimization alone does a deep disservice to the history of native peoples.

In Native America, I tell the story of the first European explorers who came to North America from the Indians’ perspective: What native peoples saw when they looked at these newcomers, their strategic calculations, how they fit the Europeans into their conceptual universe. If you look at the story of the French explorer Jacques Cartier, who sailed into the St. Lawrence River in the 1530s, or his Spanish contemporary Coronado who wandered throughout the American southwest, or Soto’s violent exercise in futility in the Southeast, or the Juan Pardo expedition, or Cabrillo’s ineffectual reconnaissance of the California coast, or even the Roanoke voyages of 1584-1590, you cannot help but see one consistent theme. It is so obvious in the surviving documents. What is clear in every account is the utter dependence of the newcomers upon the native peoples who cautiously welcomed them into their communities, cultivated them as military allies and trading partners, enlisted them in their struggles with their neighbors, and contemplated transforming them into kin. When the newcomers wore out their welcomes in North America, their enterprises were doomed, their situation worse than desperate. These European explorers discovered what they believe they discovered only because native peoples allowed them to do so. And the effects of the visits by these European sojourners were remarkably short-lived, the consequences fleeting. Even with De Soto, who many scholars long had blamed for spreading epidemic disease into the continent’s interior (a mistake I made in the first edition), we now know from the work of historians like Paul Kelton and anthropologists like Robbie Etheridge that his disastrous expedition had little long-term effect. The wasting plagues came in the seventeenth century, a product of an Anglo-American trade in Native American slaves, the scope of which was vast and mind-boggling.

Columbus Day found its origins in discrimination against Italian-American immigrants. We were here from the beginning, Italian-Americans said, and we have as great a claim to this continent as any other group. The holiday has seldom encouraged any significant and honest discussion of the consequences of the Columbian Encounter, a process which was, as historian Alfred Crosby showed a long time ago, much bigger than Christopher Columbus. It is time for the bad history and the myth associated with this day to go away, and if recognizing Indigenous Peoples’ Day helps I am all for it. Let’s talk about Columbus, to be sure, and the European invasion of America, but let’s do so with our eyes firmly upon those native peoples whose losses were Europeans’ gain, and who have endured and survived through five centuries of discrimination, dispossession, and slaughter.