It’s what we do, at least metaphorically. For historians, the destruction of monuments can be a good thing, a visceral and often-times important act of revision. It is an opportunity to replace dated and damaging interpretations of the past with more complicated, nuanced, and correct stories. We do not necessarily need to destroy Confederate statues to do this, but certainly we can reinterpret them, knock them down a few pegs, and re-write the stories that these racist monuments to white supremacy attempt to tell. Stick them in a museum, if you want, but let’s not pretend these are sacred sites.

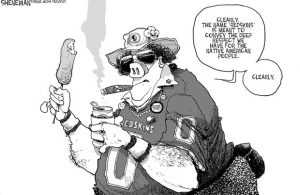

There was a news story I caught at the end of last week. Among the many vicious clowns and tiki-torch bearing, racist weenies in Charlottesville, was Mr. Jerrod Kuhn, a graduate of Honeoye Falls-Lima High School. It’s about ten miles from where I live. Kuhn was photographed marching with the white supremacists while they chanted “Jews Will Not Replace Us,” “Blood and Soil,” and “White Lives Matter.” Kuhn said, however, that he was neither a Nazi nor a white-supremacist. Rather, he was a “moderate Republican”(!) marching to protest efforts to eliminate statues and monuments commemorating the Confederacy and the cause for which it stood–White Supremacy. When some of Kuhn’s anti-fascist neighbors saw his picture with the marchers, they publicized this bit of news, arguing that local residents should know that there is a Nazi in town. And Kuhn cried foul. He was afraid. Some of his neighbors were being mean to him. Boo-Freakin-Hoo. If you dance with the devil, people are going to think you are a sinner, and the monuments Kuhn marched to protect and which commemorated the Confederacy were erected not immediately after the Civil War, but several decades later, at the beginning of the Jim Crow era. It is an interpretation of the Civil War that has endured, in the face of all the evidence, for far too long. If taking down statues which lionize slave-owners who were willing to kill US Soldiers in order to hang on to their human property and the system of white supremacy that lay at the bedrock of southern society is what’s at stake, then let them fall.

I have thought a lot about Charlottesville. I have thought about the President’s support for the so-called “Alt-Right” movement. As I mentioned in a post last week, I really do not care what the President says: systems of white supremacy are deeply ingrained. Trump has emboldened the Nazis and the Troglodytes, but those people have been living under rocks quite contentedly for generations, surfacing periodically. Even though Steve Bannon has lumbered away from the White House, and Donald Trump is saying whatever the hell it is that he occasionally says, white supremacy will endure. It is institutional, and it is part of what we are as a nation.

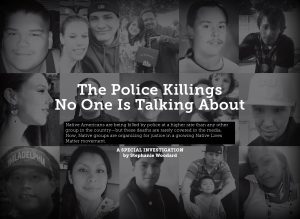

I have thought, however, about what all of this might mean to those of us who teach and study Native American history, a field in which we might not discuss white supremacy enough.

After I mo ved to Montana in 1994, one of my first trips was to visit the Little Bighorn Battlefield site, about an hour or so away from Billings. In the small visitor’s center stood a iron plaque, about a yard square, that had been placed at the battlefield by Native American activists in the summer of 1988. It read,

ved to Montana in 1994, one of my first trips was to visit the Little Bighorn Battlefield site, about an hour or so away from Billings. In the small visitor’s center stood a iron plaque, about a yard square, that had been placed at the battlefield by Native American activists in the summer of 1988. It read,

In honor of our Indian Patriots who fought and defeated the U.S. calvary. In order to save our women and children from mass-murder. In doing so, preserving rights to our Homelands, Treaties and Sovereignty. 6/25/1988 G. Magpie, Cheyenne.

You can read about the history of this plaque here. It was a protest. An attempt to replace one monument with another, a somber remem brance of the men Custer led to their deaths in June of 1876 with a monument commemorating the efforts of the Lakota warriors who fought to protect their homelands, even if the battle took place in Crow Country. Some viewed the plaque as an act of vandalism. But it forced a conversation. Custer was no hero. His men fought to eliminate Lakota people, to take their homelands, and the mineral wealth that lie beneath it. The native peoples who fought them were not obstacles to progress. But that is how they were depicted.

brance of the men Custer led to their deaths in June of 1876 with a monument commemorating the efforts of the Lakota warriors who fought to protect their homelands, even if the battle took place in Crow Country. Some viewed the plaque as an act of vandalism. But it forced a conversation. Custer was no hero. His men fought to eliminate Lakota people, to take their homelands, and the mineral wealth that lie beneath it. The native peoples who fought them were not obstacles to progress. But that is how they were depicted.

The protest mattered. It gained attention. It forced a conversation, a reconsideration. The National Park Service responded. When a permanent monument was erected at the battlefield site in 2003, the native peoples who participated in that protest, who defied the rangers and cemented their iron plaque over the list of Custer’s dead cavalrymen, came as invited guests.

History is not merely a collection of facts. You can see, for instance, how Custer has been depicted over the years. Walt Whitman described him as a Christ-like figure, one who sacrificed himself in the name of western civilization and the conquest of the American West.

From far Dakota’s canyons,

Lands of the wild ravine, the dusky Sioux, the lonesome stretch, the

silence,

Haply to-day a mournful wall, haply a trumpet-note for heroes.

The battle-bulletin,

The Indian ambuscade, the craft, the fatal environment,

The cavalry companies fighting to the last in sternest heroism,

In the midst of their little circle, with their slaughter’d horses

for breastworks,

The fall of Custer and all his officers and men.

Continues yet the old, old legend of our race,

The loftiest of life upheld by death,

The ancient banner perfectly maintain’d,

O lesson opportune, O how I welcome thee!

As sitting in dark days,

Lone, sulky, through the time’s thick murk looking in vain for

light, for hope,

From unsuspected parts a fierce and momentary proof,

(The sun there at the centre though conceal’d,

Electric life forever at the centre,)

Breaks forth a lightning flash.

Thou of the tawny flowing hair in battle,

I erewhile saw, with erect head, pressing ever in front, bearing a

bright sword in thy hand,

Now ending well in death the splendid fever of thy deeds,

(I bring no dirge for it or thee, I bring a glad triumphal sonnet,)

Desperate and glorious, aye in defeat most desperate, most glorious,

After thy many battles in which never yielding up a gun or a color,

Leaving behind thee a memory sweet to soldiers,

Thou yieldest up thyself.

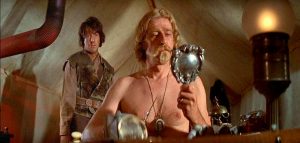

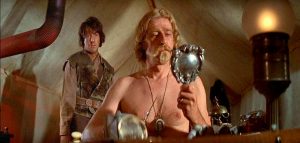

A century later,  Richard Mulligan portrayed Custer in “Little Big Man” as an unhinged madman, a preening martinet, in love with his own reflection, and lusting for Indian blood. He spouted lines that would have sounded familiar to a movie audience exhausted and angry about the Vietnam War. He represented all the foolishness, the arrogance, and the stupidity that led the United States into an imperial war it could not win. Custer, Westmoreland, light at the end of the tunnel, we must always advance. It was a stunning revision of Custer’s carefully cultivated image.

Richard Mulligan portrayed Custer in “Little Big Man” as an unhinged madman, a preening martinet, in love with his own reflection, and lusting for Indian blood. He spouted lines that would have sounded familiar to a movie audience exhausted and angry about the Vietnam War. He represented all the foolishness, the arrogance, and the stupidity that led the United States into an imperial war it could not win. Custer, Westmoreland, light at the end of the tunnel, we must always advance. It was a stunning revision of Custer’s carefully cultivated image.

Interpretations change. Monuments are not history. They are interpretations of history. And as such, they are not sacred. They are open to challenge, to question. And if the claims they make are wrong or over-simplified or pernicious–Custer was heroic, or the South fought for “States’ Rights,” for example– than they ought to be replaced, revised, rewritten. My point is that we historians, when we do our jobs well, destroy monuments ALL. THE. TIME. We ask tough questions. We challenge long-cherished assumptions. We are not precious, and we should hold nothing sacred but a determination to work the sources thoroughly and honestly in order to get the story right.

And then there is the story of Juan de Oñate’s foot. A statue of the Spanish Conquistador, considered a “Founding Father” of New Mexico, stood in the town of Alcalde. In January of 1998, as the 400th anniversary of his arrival in New Mexico approached, protestors armed with a chainsaw cut the right foot off the  statue. For them, this conquistador was no hero. They were, in effect, writing an alternative version of the Oñate story, commemorating the violent Spaniard’s brutal order to cut the right foot off of two dozen Acoma Pueblo prisoners who had resisted his advance. I wrote about this event in Native America. The sculptor repaired the statue, but the missing foot never was returned.

statue. For them, this conquistador was no hero. They were, in effect, writing an alternative version of the Oñate story, commemorating the violent Spaniard’s brutal order to cut the right foot off of two dozen Acoma Pueblo prisoners who had resisted his advance. I wrote about this event in Native America. The sculptor repaired the statue, but the missing foot never was returned.

We can call this act vandalism, or the destruction of public property, the sort of stuff that Vice-President Mike Pence has said he deplores. It was those things, but it also was an act of reinterpretation, of historical revision. Douglas Seefeldt made this point in a paper entitled “Oñate’s Foot: Histories, Landscapes, and Contested Memories in the Southwest,” published in Across the Continent: Jefferson, Lewis and Clark, and the Making of America, published by the University of Virginia Press in 2005. Seefeldt edited this volume, along with Jeffrey L. Hantman and Peter Onuf. While some might excuse Oñate’s violence, and celebrate his founding of the Spanish province that became the state of New Mexico, and his bringing the cattle industry to what became the American Southwest, the people who removed the foot from the statue reminded New Mexicans of another side to the story, and demonstrated that history consists of many narratives and many voices. Not all these voices are heard. Not all of them are listened to. And sometimes, to register, to move the debate, dramatic acts are necessary.

I like this poem that tells the story of the removal of Oñate’s foot, and the subsequent celebration of another, larger, statue of the conquistador erected near El Paso:

“The Right Foot of Juan De Oñate”By Martín Espada

On the road to Taos, in the town of Alcalde, the bronze statue

of Juan de Oñate, the conquistador, kept vigil from his horse.

Late one night a chainsaw sliced off his right foot, stuttering

through the ball of his ankle, as Oñate’s spirit scratched

and howled like a dog trapped within the bronze body.

Four centuries ago, after his cannon fire burst to burn hundreds

of bodies and blacken the adobe walls of the Acoma Pueblo,

Oñate wheeled on his startled horse and spoke the decree:

all Acoma males above the age of twenty-five would be punished

by amputation of the right foot. Spanish knives sawed through ankles;

Spanish hands tossed feet into piles like fish at the marketplace.

There was prayer and wailing in a language Oñate did not speak.

Now, at the airport in El Paso, across from Juárez,

another bronze statue of Oñate rises on a horse frozen in fury.

The city fathers smash champagne bottles across the horse’s legs

to christen the statue, and Oñate’s spirit remembers the chainsaw

carving through the ball of his ankle. The Acoma Pueblo still stands.

Thousands of brown feet walk across the border, the desert

of Chihuaha, the shallow places of the Río Grande, the bridges

from Juárez to El Paso. Oñate keeps watch, high on horseback

above the Río Grande, the law of the conquistador rolled

in his hand, helpless as a man with an amputated foot,

spirit scratching and howling like a dog within the bronze body.

Interpretations of Native American history are everywhere, and I often encourage students to seek them out, to engage them in a debate, to interrogate their biases and assumptions. Good comes from this. Every day from first through sixth grade I saw this mural on the wall of Our Lady of Assumption Church in Ventura, where I grew up and went to elementary school. It presents a rosy picture of the arrival of the Spanish priests at Mission San Buenaventura, one not at all consistent with how scholars see that encounter today. Nobody has suggested removing this mural to my knowledge, but it stands testament to an interpretation highly favorable to the Catholic Church.

knowledge, but it stands testament to an interpretation highly favorable to the Catholic Church.

We write history; we do not create monuments. Our purpose is not civic education or instilling patriotism. As I have said before, history is the study of continuity and change, measured across time and space in peoples, institutions, and cultures. That requires asking tough questions, researching relentlessly, and presenting answers that are sometimes painful to hear. And too much of the history that has been included on these Confederate monuments and monuments to conquistadors and conquerors is, quite simply, bad history.

In two weeks the town of Geneseo, where my college is located, will be commemorating the 1797 “Treaty of Big Tree.” It is a big deal in town. As a guest of the college, you might stay in the Big Tree Inn. Dining halls on campus are named after Mary Jemison, who knew much about the treaty, and Red Jacket, who got screaming drunk before he signed it. For those who do not want to drink where students drink, the tavern at the Big Tree is one of a small handful of choices along Geneseo’s short main street. If you want to take in the sights, you can go to the Livingston County Historical Society, spitting distance from the campus, and see what its curators claim is an actual piece of the “Big Tree,” under which the treaty was negotiated. And according to a historical marker located in a campus parking lot, this treaty was significant. The sign reads, “Treaty Of Big Tree: Site Of Memorable Treaty Releasing Seneca Title To 3,600,000 Acres Of Land September 15, 1797.”

Releasing title. 3. 6 million acres. Wow. This treaty was an alcohol-soaked affair in which Thomas Morris, the non-bankrupt son of the bankrupt financier of the American Revolution and not-too-successful land speculator Robert Morris, employed bribery and alcohol to obtain signatures to a grotesquely corrupt real estate transaction. The Senecas, who had little choice, signed over the right to nearly all of the land in New York State west of the Genesee River save for eleven reservations. Over time, those reservations were whittled down to four, and then two, and now three. In return for this massive cession, and the bribes he agreed to pay several Seneca leaders, Thomas Morris invested $100,000 dollars in stock of the Bank of the United States, the interest of which was paid to the Senecas most years thereafter. Some years the amount came to nearly six thousand dollars; other years it was half that. Why did this happen? Stuart Banner answers tough questions like this in his excellent How the Indians Lost Their Land, a book I use in my Indian Law course. The territory was massive; the Senecas’ population small. The speculators and the settlers were coming. Better to sell now, get something, and preserve a few key locations than walk away empty-handed. Dispossession. Land loss. The removal from homes and homelands. That story is given short-shrift in the celebratory histories of Geneseo and Livingston County. Signs like this one, as the Haudenosaunee scholar Rick Hill has argued, should be re-written. Rick put together a pamphlet some years ago in which he wrote brief retorts to these ethnocentric markers that seemingly justify the dispossession of Haudenosaunee people and the resulting Iroquois diaspora.

So to those of you who marched in Charlottesville, or sympathize with them, let me make this clear: when we historians suggest that your markers and monuments ought to come down, we are not trying to steal your history and heritage. History belongs to no one and your heritage, well, good luck with that. You are on your own. We are suggesting that the interpretation of the past that you cling to, rather, is not only incorrect and oversimplified, but in some cases pernicious and a justification for past evils and continuing historical crimes. We hope we can reason with you, and persuade you with evidence to see things our way. We are educators, after all, who have spent our adult lives studying history. We know some stuff. (Some of the other people complaining about you? Yeah, they think you’re racist assholes, and some of them want to beat you up, but I don’t speak for them). Facts, evidence, explanation: That is the world of the historian. Myth, fantasy, and ideological comfort food–that is where the monument boosters stand. Our goals are different. Yours are about justifying your views of the past. Ours? We like to think that we are speaking and writing about the truth.

And here’s a challenge for those of you who do not like what we say. I tell my students this every semester. Ask us for the evidence. I promise you, we will do the same. We will support our claims with evidence, and ask that you do, too. If you hear something that you do not believe, ask us for the proof. That is fair. I tell my students, it is entirely fair for them to ask their history professors not only, “What is the evidence for this claim?” but, also, “So What? Why does this story matter?” No historian worth his or her salt will be threatened by that question. We can take it. Can you?